Six reasons why inflation may feel like gum on your shoe

Quantitative Investments

Inflation may have come to feel like gum on your shoe – it is annoying and, above all, hard to remove. Sticky inflation is a scenario that has been in the cards since consumer prices started climbing in early 2022. But now it seems to receive more weight as a probable outcome. After being on a surprisingly straight downward trend for four months, US and Eurozone inflation has started to dig in its heels as revealed by recent data releases for January. There are six reasons for this display of stubbornness which may disappoint those who thought inflation would come off easily.

Already the strong US labor market report in January triggered an interest rate repricing but the publication of January US inflation numbers accelerated the rise in rate expectations. Currently, the market is still rather optimistic and expects the Fed to end its tightening cycle in August followed by rate cuts in 2024. If this comes true or not depends on the stickiness of inflation for which we see several structural drivers1 that will make it difficult for central banks to push inflation back down to target levels without triggering a recession.2

This is not to say that inflation has cancelled all of the recent and longer-term deflationary trends3 - on the contrary, these are still alive and kicking. Even in the short term there are cyclical drivers which make a strong case for the possibility of a meaningful decline in inflation already this year as well as the next. Unclogging supply chains, recently declining commodity prices and the global economy slowing down are powerful forces leading to negative inflation base effects over the next few months at least. However, structural inflationary drivers have been gaining weight and could prevent inflation from falling below central bank targets in a sustainable fashion over the next few years. This circumstance carries important messages for investors who want to target attractive returns over the years to come.

Reason 1: elevated inflation is the norm rather than the exception

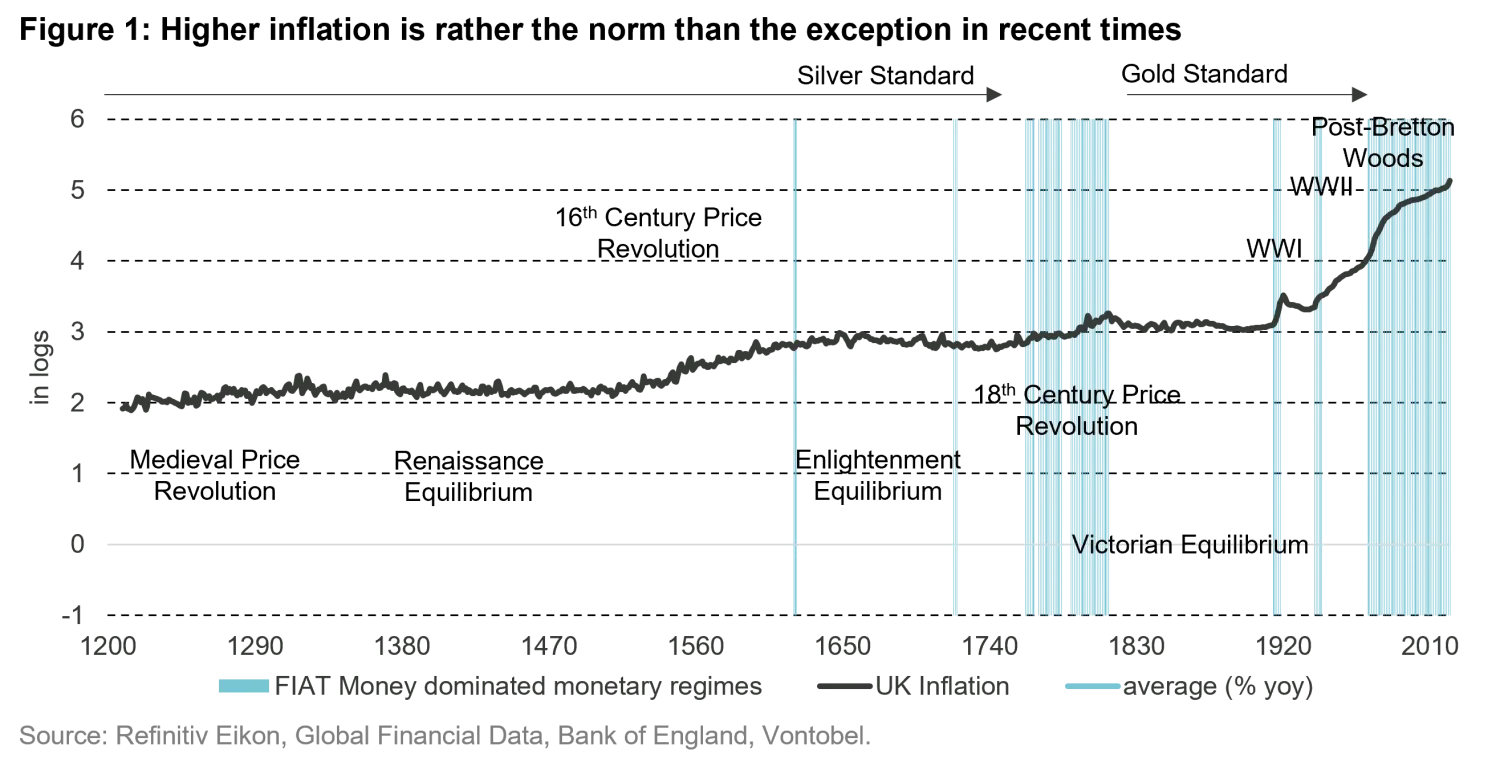

Elevated inflation levels might seem like a curious quirk of recent times, but they were in fact the norm for most of recent history. This becomes apparent when breaking down historical data into metal- and fiat-based monetary systems4. While in metal-based monetary systems inflation was nearly non-existent with an average value of only 0.8%, fiat-based monetary systems, which rose to prominence in the 20th century, display an average figure of 4.3%. Since the breakdown of Bretton Woods, which was the last metal-based monetary system in place, inflation has even been 5.1% on average. Plus, no single developed country – not even Japan – has managed to keep average inflation below 2% between 1973 and today. Therefore, it is a false conclusion that phases of inflation well above 2% are the exception in fiat-based monetary systems. They have rather been the standard (figure 1).

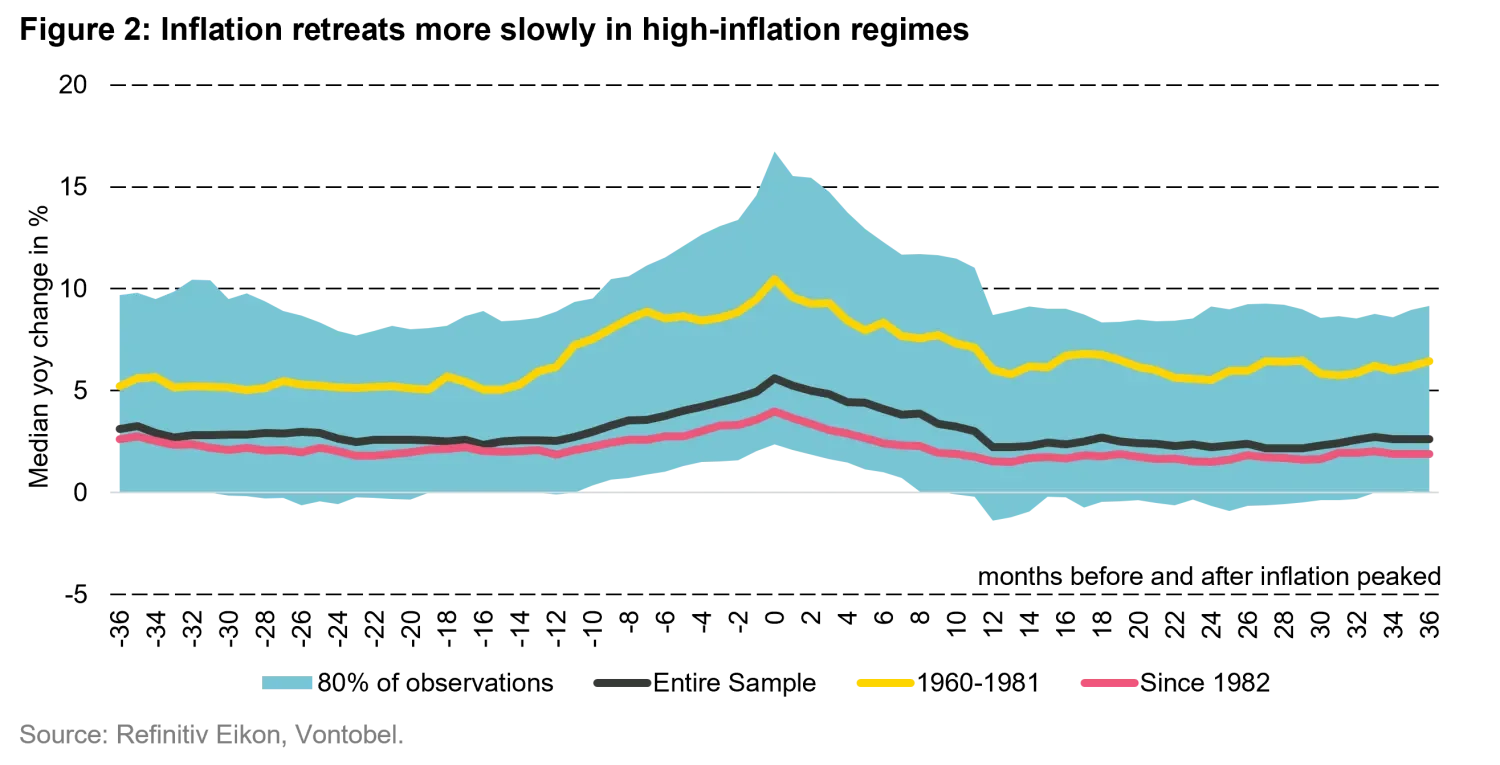

Moreover, our analysis shows, that the higher inflation is allowed to go, the stickier it becomes afterwards. An investigation of inflation regimes in ten industrialized countries since 19205 demonstrates that inflation usually falls fast after its peak. However, in high-inflation periods such as the 1960-80s, inflation can take longer to retreat and often stabilizes at a higher level than before its rise (figure 2). Therefore, we believe it is rather questionable if inflation will make a swift return to central banks' targets in a sustainable manner over the next two years.

Reason 2: risks of supply shocks linger on

In the absence of wars in developed and major emerging markets as well as energy crises, the global economy has been spared the pain of severe supply-side shocks since the 1980s. However, the tables have now turned. The COVID crisis and the Russia-Ukraine war have severely disrupted supply chains worldwide laying bare global dependencies. The prediction of geopolitically driven price shocks remains an incredibly difficult task, but geopolitical tensions are likely to remain high in Europe (Ukraine/Russia), Asia (Taiwan) and the Middle East (Iran/Israel) and the risk of a prolonged or renewed supply shock is not negligible.

The implications of the political determination to hold on to zero-carbon emission targets by 2050 might be better to predict but result in an equally bleak picture. As households and corporations are incentivized or, at times, even forced to transition to renewable energy sources, supply disruptions and therefore price pressure could easily arise at least in the early stage of the transition. The production of 20 million electric vehicles alone – a number possibly reached in 2025 – is likely to exceed current global production capacity of certain metals by far.6

Reason 3: inflation is a remedy to growing government debt

Government debt has surged over recent years and reached new highs during the pandemic crisis due to massive COVID-related spending measures. While debt creation tends to be inflationary, paying off debt is the opposite. Governments have voiced their willingness to be more disciplined on spending going forward. The question is can they? According to projections of International Monetary Fund data, not really7. First, the war between Russia and Ukraine has not only shown that supply chains are vulnerable, potentially requiring a costly reorganization, but that countries might have to increase their defense spending. Looking at defense expenditures, in particular mainland Europe has catch-up potential. According to NATO8, most countries did not meet the defense spending targets of 2% to GDP in the past. In reversal of this trend, many NATO governments indicated their willingness to not only meet but even exceed the spending target in the coming years. Second, consumer protection schemes might continue to be necessary in the future since energy inventories could deplete again next winter.

Funding these expenditures is a tricky undertaking since one-sided increases in spending won’t work - at least this is what the 2022 UK fiscal crisis revealed when the announcement of higher expenditures without cuts elsewhere was severely penalized by investors and markets. And this should be true for any country with a higher debt burden, Italy being another case in point. However, there might be a way out: inflation.9 As the nominal value of debt must be paid back, higher inflation will lead to higher nominal government revenues and make it easier for them to repay the debt stock. Even though central banks have a clear duty to fight inflation, financial stability and sustainable growth matters for them at least indirectly too, which may tempt them into letting inflation run a bit higher.

Reason 4: demographics fuel inflation

There are two different demographical trends that may have inflationary effects.

Generally, an ageing population is assumed to exert deflationary pressure because older people consume less goods and services leading to less demand - a so-called savings glut. However, this conclusion leaves the labor supply side by the wayside which is an important consideration since a shrinking labor force may lead to a lower quantity of goods produced unless productivity compensates for the effects of a declining labor force or higher wages attract more foreign workers. In particular China and India, two major countries that produce many of our goods, will (India), or do already now (China), face demographical headwinds over the upcoming decades, which may lead to wage pressures and rising production costs in Asia.

Moreover, the US, which is the biggest economy and consumer market in the world, is likely to experience a demographic tailwind for the first time since the baby boomer phase in the 1960s. Over the next decade, population data provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the working age group of the 20-55 years old will likely rise significantly faster than between 2000-2020. As this age bucket has a high consumption-to-disposable-income ratio, the correlation between the growth of this age bucket and core inflation is high.

Reason 5: supply chain reshuffling drives up production costs

Globalization has been losing pace since the Great Financial Crisis, as two major drivers supporting the trend have weakened over the past decades. While tighter banking regulation may have passed its peak and may become less of a headwind going forward, supply chain reshuffling gained momentum in recent years. Even though the relationship between the US and China started to cool off well before 2016, it was the Trump administration that initiated a trade war triggering a shift of production facilities from China to other Asian producers. This trend of supply chain reorganization gained traction during the COVID crisis in 2020/21 and became a necessity for many companies more recently with the Ukraine-Russian war. These supply side disruptions uncovered vulnerabilities calling for near-shoring by providing the incentive to bring production facilities back into domestic spheres of influence. This tends to be inflationary as corporations weigh supply chain security higher than having production facilities in low production cost countries.10

Reason 6: economies have been running hot

Many countries seem to have overstimulated their economies during COVID-19, with stimulus packages exceeding output gaps caused by the pandemic crisis. In 2020, government deficits rose above 11% in G7 countries and have stayed close to 5% until today. This has helped people to bounce back,11 leading to significant pent-up demand. The following labor market tightening led to a surge in wage growth not seen in G7 countries for decades. As wage growth and the wage share of national income are rising, the pressure on corporations to pass costs on to the consumer has increased too. As the global economy starts to slow down, labor market conditions may ease, but its resilience argues for at least a couple of quarters for wage growth that is incompatible with the 2% inflation target.

Implications for investors

While the reasons for inflation to remain sticky should now be abundantly clear, what does this mean for investors? We highlight four aspects to watch out for:

(1) Less predictable monetary policy

Inflation makes monetary policy more uncertain. For most central banks the single most important job is to keep inflation in check, often around 2 percent. Even though only a few central banks, including the Fed, have an official dual mandate of achieving price stability and growth (full employment) at the same time, all central banks face a tradeoff between growth and inflation, as both impact each other. Therefore, central banks generally try to manage both, keeping inflation stable around its target and counteract the risks of economies overheating as well as recessions. When inflation is absent, the job of a central banker becomes much simpler. Now that it is back, central bank policy has become more unpredictable.

(2) Higher financial market volatility

As central bank behavior becomes less predictable, market volatility can be expected to go up as investors will try to anticipate monetary policy moves and its effects on markets. Since the reaction function of central banks is shrouded in uncertainty, this process is likely to go hand in hand with more pronounced market moves as assets continuously re-price in accordance with changing market expectations.

(3) More macroeconomic data volatility

Higher financial market volatility usually causes higher macroeconomic volatility. As financial markets become more volatile refinancing conditions for corporates do as well leading to higher macro volatility and negative feedback loops.12 Therefore, higher macroeconomic volatility should lead to shorter business cycles and to a more dynamic trading environment.

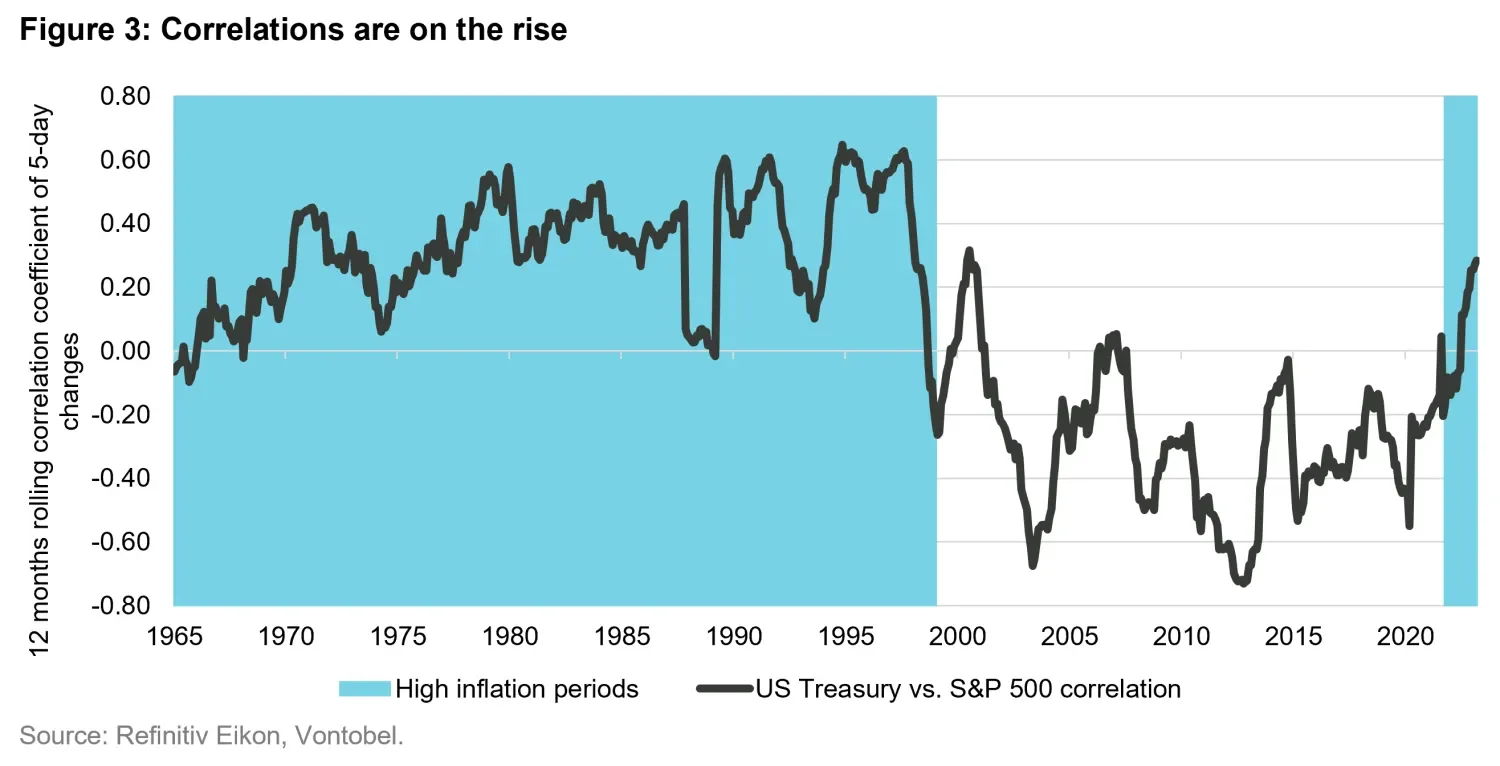

(4) Rising correlations

As inflation gradually disappeared from central banks' problem-solving equation, the long end of the yield curve was mainly driven by central-bank asset purchasing programs and growth expectations. Both factors added significantly to the negative correlation pattern between equities and bonds over the business cycle which has provided investors with precious stabilizing portfolio effects. However, as inflation has come back to the agenda of central banks, the Great Moderation, a period of great financial market and macroeconomic stability, has likely come to an end ushering in not only higher risks for bonds as inflation diminishes the present value of their cashflows but also for equities that tend to suffer when risks of overtightening increase in a bid to subdue inflation. Ultimately, this pushes up correlations between equities and bonds raising the risks for investor portfolios that used to bank on the balancing effects of equity and bond exposures (figure 3).

Important Information: Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Any projections or forward-looking statements herein are based on a variety of estimates and assumptions. There is no assurance that information provided regarding future financial performance of countries, markets and/or investments will prove accurate, and actual results may differ materially.

1. See our latest white paper “

Breaking with the past: the new face of financial markets in 2023 and beyond

”

2. See as well Ball et. al. (2022) “

Understanding U.S. Inflation during the COVID Era”

. WP no. 2022/208

3. Such as inequality or technological advancement (robotics, 3D-printing, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, etc.) to just name two.

4. A fiat currency is a national currency not pegged to the price of a precious metal.

5. We analyze 158 inflation peaks since 1920’s (if available) in ten developed countries

6. See McKinsey (2022) "

Power spike: How battery makers can respond to surging demand for EVs

”

7. See IMF Fiscal Monitor “Helping People Bounce Back”, October 2022

8. See NATO (2021) “

Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2021)

”, Press Release, PRCP (2021) 094

9. See Vontobel (2019) “

On debt mountains and monetary policy adventures – Can modern monetary theory help us conquer the mountain of debt?

”

10. See Vontobel (2019) “

The Next Digital Superpower – Scenarios for the US-China conflict and implications for the global economy

”

11. See IMF (2022) “

Fiscal Monitor – Helping People bounce back

”, October 2022

12. See for example Schwert (1989) “Why Does Stock Market Volatility Change Over Time?”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. XLIV, no. 5