Breaking Bias

Multi Asset Boutique

The same cognitive machinery that powers our reasoning also distorts it, leading to biases that don’t always align with reality. This isn’t just a human problem; it’s baked into commonly used AI and even in how we see ourselves. Nowhere is the disconnect between perception and fact more stubborn than when it comes to gender in finance.

This Quanta Byte takes a hard look at the perception vs. the reality of women in finance by challenging hard-wired narratives with a data-driven view. I start by recounting an unexpected AI experiment, which forced me to confront my own blind spots, revealing how my perception doesn’t align with that of the world. I then follow up with Prof. Renée Adams, who shares research that upends conventional wisdom: women in finance aren’t necessarily more risk averse than men; adding women to boards isn’t necessarily a panacea; and the so-called meritocracy often overlooks systemic barriers.

A personal AI experiment

For most of my career, I've identified as a mathematician and quant -- full stop. Gender wasn't part of the equation for me. Of course, I was aware that women were a minority in my field, but I never thought much about what that meant for me personally. I always assumed that meritocracy ruled, no matter what. It took me a couple of decades to realize that my gender-blindness, whether intentional or unintentional, was naïve.

Enlightenment struck when Prof. Renée Adams from Oxford University interviewed me about gender imbalance among finance professors in Switzerland. This was part of her work for the AFFECT (Academic Female Finance Committee) initiative of the American Finance Association, which she co-founded in 2015. The conversation was humbling -- biases, structural barriers, and subtle differences in perception weren’t just abstract concepts but well-documented realities, backed by data and decades of research, that I had been completely unaware of.

Then, I accidentally ran my own little AI experiment, that really drove the point home.

I am an avid user of AI assistants, which have entirely replaced search engines for me. AI knows my life well, both personal and professional. So, I asked it to generate an image of my day based on what it knows about me. The result was a spot-on depiction: my tidy desk, books stacked in the back, finance-heavy screens in the front, swimming gear and bike in one corner, a few children’s toys, neatly stacked, in the other corner. Except: the person sitting and doing the thinking was a man. He looked balanced, focused, at ease. Curious, I corrected the gender. The image changed completely. No more sleek workstation -- now I was in sweatpants, sitting at a kitchen table with my boys, working on my laptop with one hand and prepping dinner with the other.

AI had nailed my professional identity until gender entered the equation. Its bias did not surprise me. What did was finally understanding my blind spot: it wasn’t that I had been gender-blind all my life, but that I had an absence of bias about myself. And my unbiased view likely didn't align with others' perception of me, human or AI.

Perception versus reality in finance: a data-driven view

Finance is no exception. Perception often lags reality, shaped more by biases than data. And when it comes to women in finance, certain myths persist despite little evidence to support them. One common myth is that women approach investing, risk, or leadership fundamentally differently. The numbers tell a different story, but the bias persists . So, I reached out to Renée, keen to understand how her research challenges some of these misconceptions and what I might have overlooked. Here is our exchange.

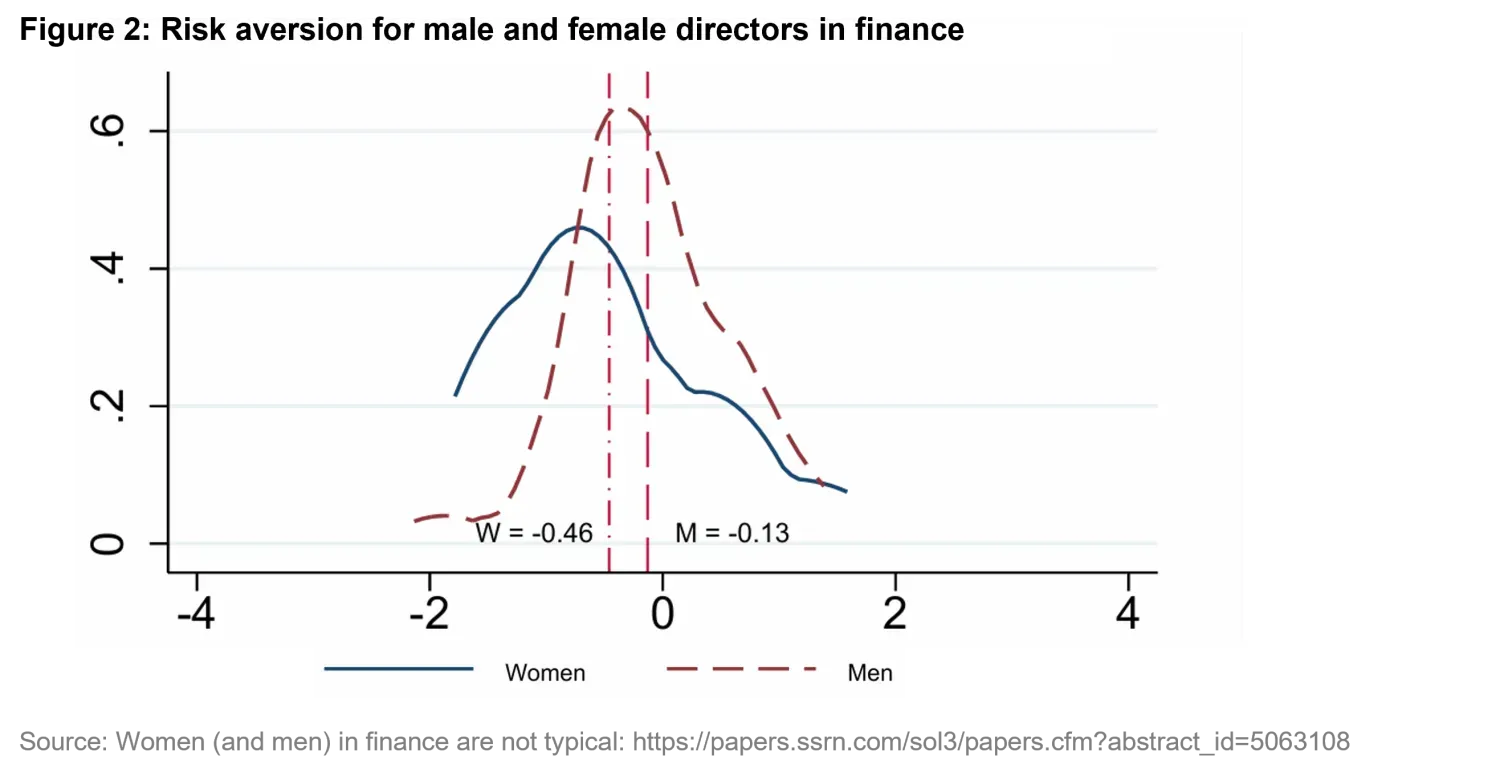

OM: In my past research, I’ve explored risk aversion through the lens of decision theory. But I never stopped to consider the gender of Homo Oeconomicus. Are women really more risk-averse than men when it comes to finance?

RA: No. My research shows that women in finance may be less risk-averse than men in finance. When my co-author, Patricia Funk, and I asked directors how much they would pay to avoid investing in a risky lottery, male directors said they would pay 7.5% more than female directors, so on average female were less risk-averse than male directors.1 When we examined directors of financial firms, this gender gap increased to 21.5%. So, in finance, female directors were even less risk averse than their male counterparts than they were in general. This may seem counterintuitive, but they should not be to a Homo Oeconomicus who understands economic models of selection. Women (and men) who choose to be in finance and are chosen to be in finance must be attracted to risk. Since finance is a male-dominated field, this attraction may need to be particularly strong for women.

OM: Another topic that fascinates me, both as a researcher and as an investment strategist, is diversification. On a personal level, I’m also a strong advocate for cognitive and experiential diversity. But what about diversity in boardrooms and leadership? Does having more women on boards lead to more ethical or conservative decision-making?

RA: I am also a fan of diversity in many forms. Precisely for this reason I think it is important to recognize the diversity of characteristics that women (and men) exhibit. Regarding the question about women and ethics: My research highlights that the correlation between gender and ethical decision-making on boards is not obvious. The reason is, once again, selection. While there is research suggesting than women on average are more ethical than men, we have to remember that the people sitting on boards are not “typical”. Moreover, directors are not randomly assigned to boards. Will boards choose to appoint female directors who are more ethical than the men on the board? Maybe. But also: maybe not.

OM: And what about diversity and firm performance?

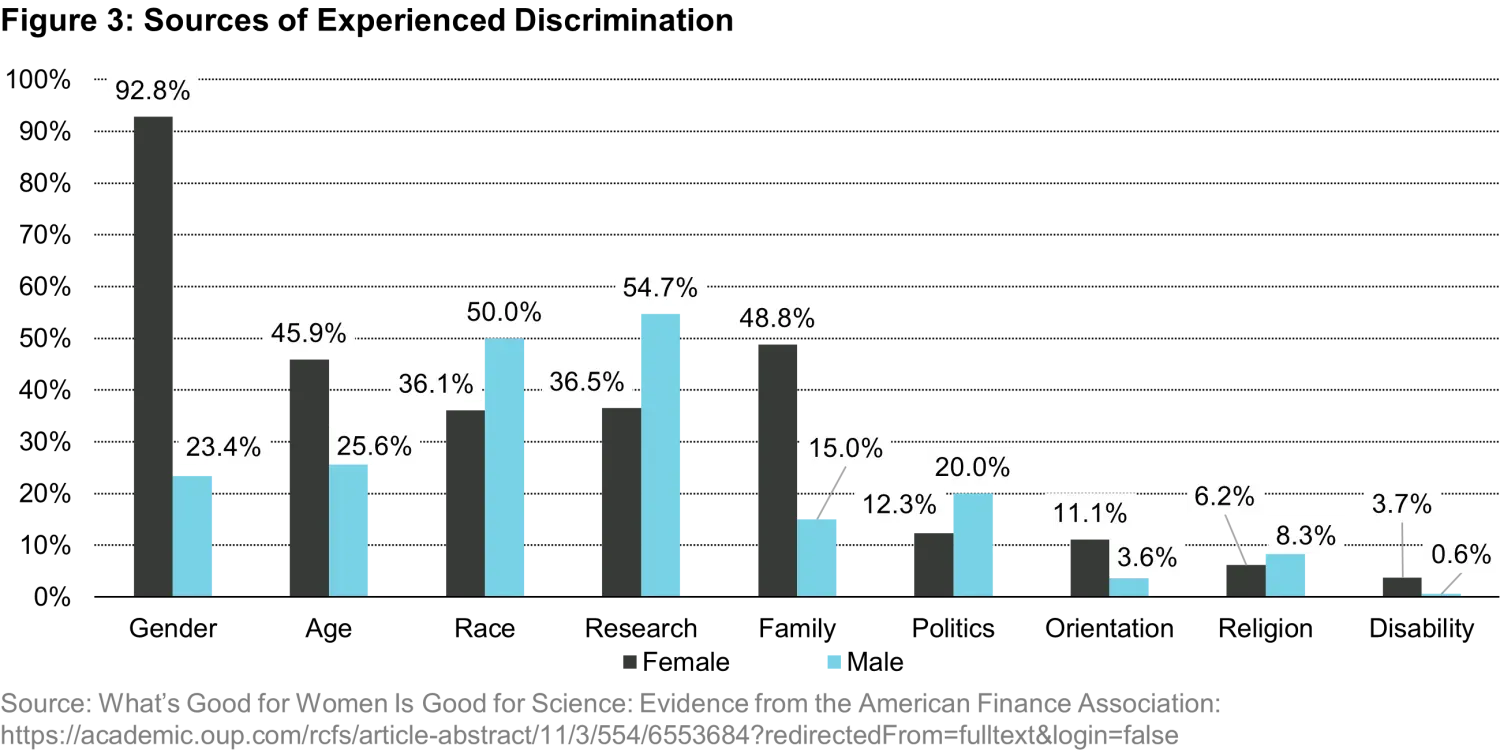

RA: Related to my points above, increasing gender diversity on boards may or may not increase performance. If boards choose to appoint women who are similar to existing board members or whom they do not empower to enact change, why would performance increase on their appointment? But the absence of a link between performance and diversity does not mean one should not appoint women to boards. The continued underrepresentation of women on boards and in many leadership positions - including in finance and in academia - highlights the persistent structural barriers to innovation and growth in society. If a board has no women, one should ask serious questions about why not. Diversity may or may not add value, but discrimination is a losing proposition.

OM: It took me a long time to realize that the playing field isn’t as level as I assumed. The “leaky pipeline”2 in research and in finance isn’t about lack of ability, but perhaps about talent that never gets fully realized. It’s a complex challenge, with debates spanning from claims of a talent shortage to deeper structural and cultural barriers. What’s your take on what’s really driving this and how we can start to fix it?

RA: My take is that structural and cultural barriers drive the leaky pipeline. In a paper I am working on about the mutual fund industry, my co-author, Min Kim, and I show that following fund closure female managers are more likely to exit the fund family and the industry than their fellow male managers. Interestingly, female managers’ exit probability is the same as the exit probability for male managers in all male fund families. So, standard explanations about gender gaps in preferences cannot explain women’s higher average exit rate. There is also no gender gap in fund returns. Instead, we document that male managers in diverse fund families benefit from diversity. Following fund closure, their exit probability is lower than that of both female managers and male managers in all male fund families.

This is an especially interesting finding given recent political arguments about how DEI hurts men. When people argue that DEI hurts men, as many unfortunately do, they are typically thinking about hiring, not career progression. But while DEI may help women get a foot in the door, it does not ensure they are treated equally once hired.3

Relatedly, my co-author Jing Xu and I show that in countries that are more gender equal, there are more female scientists. Again, this suggests that culture is an important factor that explains women’s representation.

In terms of how to fix the leaky pipeline: we must stop focusing only on the pipeline (the hiring stage) and start thinking about how to support the women who are hired. This does not mean forcing the women to fit the system. It means changing the system to support the women.

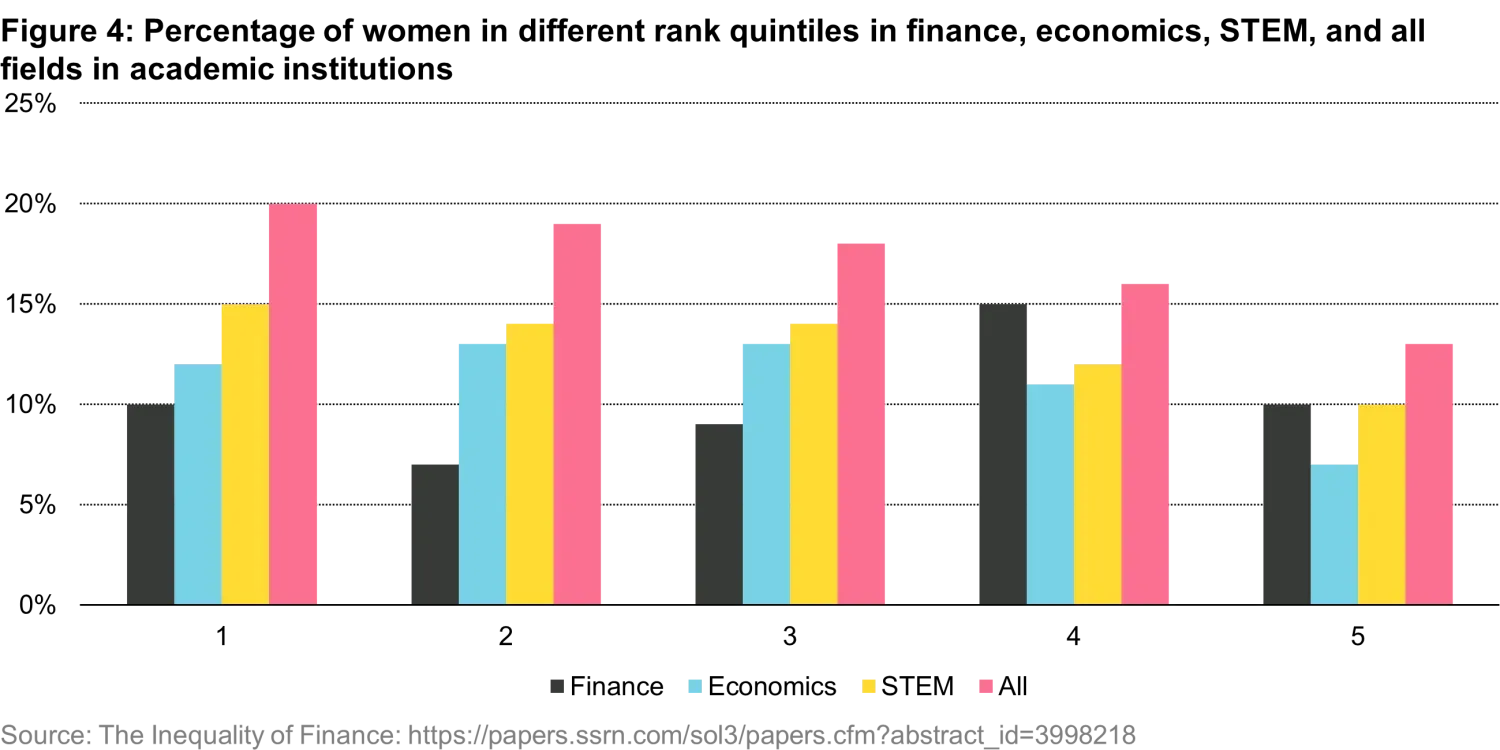

OM: In academia, economics seems to be lagging other STEM fields in terms of representation. But finance seems to be worse than economics, which eventually trickles down to the finance industry. Why do you think that is?

RA: Your perception is spot on. My co-author Jing Xu and I show that finance academia is worse than economics and other STEM fields when it comes to women’s representation at the top.4 I think our results suggest that the myth of meritocracy can explain this. It turns out that in economics and finance, academics have particularly strong beliefs that to be successful in the field you need to be brilliant. In our paper we show that these perceptions of brilliance can help explain women’s underrepresentation in finance.

I suspect that the importance of beliefs about brilliance can be explained by the fact that financial economists believe that markets work. If you believe markets work, then you also believe that those who are talented rise to the top and those who are less talented do not. Unfortunately, financial economists sometimes forget that the market only works if the assumptions necessary for it to work hold. These assumptions (liquidity, transparency) don’t hold in academia. That is why I call it a myth of meritocracy.

The myth of meritocracy

For as long as I can remember, I believed that hard work and talent were what mattered most. I focused on ideas, research, and results – never gender. The merit of meritocracy. But once again, Renée has reminded me that our assumptions often mislead us. Challenging misconceptions thus requires as much unlearning as learning. If our perception of the world is shaped by bias, then data can serve as a guide to break the bias. But if our perception of ourselves is truly free from bias, then hopefully no correction is needed. For I am still a mathematician and quant – not a woman amongst mathematicians and quants. Full stop.

About Renée Adams

Renée B. Adams is a Professor of Finance at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, and a Fellow of the European Corporate Governance Institute. She currently holds the presidency of the Midwest Finance Association and is VP-Financial Education at the Financial Management Association. Renée is an expert on corporate governance, bank governance and gender. Her work has a strong policy orientation and draws on economics, finance, management, and psychology. In her work, she explores group decision-making and how group identity (typically gender), information, culture, preferences, and values moderate decision-making. Her 2009 co-authored paper “Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance” is the most cited paper in the literature on board diversity. Her recent research focuses on women in the art world, and she is currently exploring comic-making as a medium for conveying scientific ideas that challenge people’s beliefs. Renée’s interest in diversity is not limited to research. She co-founded AFFECT, the American Finance Association’s committee for women, in 2015 and chaired it until 2020.

1. Figure 2 displays the results of an experiment eliciting the risk aversion parameter of male and female directors. Higher numbers reflect a higher level of risk aversion. The heights of the densities at any point represent the likelihood of risk aversion values around that point. Thus, densities convey a more complete picture of gender differences than the averages that are the focus of common discourse.

2. The leaky pipeline refers to the systemic loss of women and underrepresented groups at various career stages due to structural barriers, biases, and lack of support, preventing their progression into leadership roles.

3. In fact, Figure 3 points to the opposite. It displays the results of a questionnaire on the sources of experienced discrimination in the workplace, for men and women separately. For each discrimination source (gender, age, race, etc), each bar displays the percentage of men and women that have experienced the specific type of discrimination. Clearly, gender represents one of the most common sources of discrimination for women.

4. Figure 4 displays the percentage of women in different rank quintiles in finance, economics, STEM subjects, and all fields in academic institutions. In finance, the percentage of women among the top 3 quintiles is consistently smaller than all other subjects. This implies a lack of representation of women amongst top ranked finance academics compared with other subjects.

References:

Adams, Renée B. and Xu, Jing, “Sex, Science, and Society”. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5105526 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5105526

Adams, Renée B., “Women (and men) in finance are not typical” (November 19, 2024). Revue d’économie Financière, March 2024, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5063108 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5063108

Adams, Renée B., and Kim, Min, “The Diversity Gap”, Working paper.

Adams, Renée and Xu, Jing (2023), “The Inequality of Finance”, Review of Corporate Finance: Vol. 3: No. 1–2, pp 35-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/114.00000035

Adams, Renée and Patricia Funk (2012) “Beyond the Glass Ceiling: Does Gender Matter?” Management Science, 58 (2), pp. 219-235.

Important Information: The content is created by a company within the Vontobel Group (“Vontobel”) and is intended for informational and educational purposes only. Views expressed herein are those of the authors and may or may not be shared across Vontobel. Content should not be deemed or relied upon for investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.