What are covered calls?

Quantitative Investments

Premium Equity Income (1 of 3)

Adding income to equities

In this three-article series, we revisit covered call strategies. This article introduces the basic workings (the “what”) and payoff implications. In the second, we’ll argue why covered calls offer a compelling way to play equities in the new decade (the “why”). In the third, we will give a glimpse into our special investment capabilities (the “how”) and provide readers with details on how to capitalize on the opportunity.

What are covered calls?

Put simply, covered calls are strategies in which investors hold a long position in an underlying stock (or index) and simultaneously sell a call option against it.

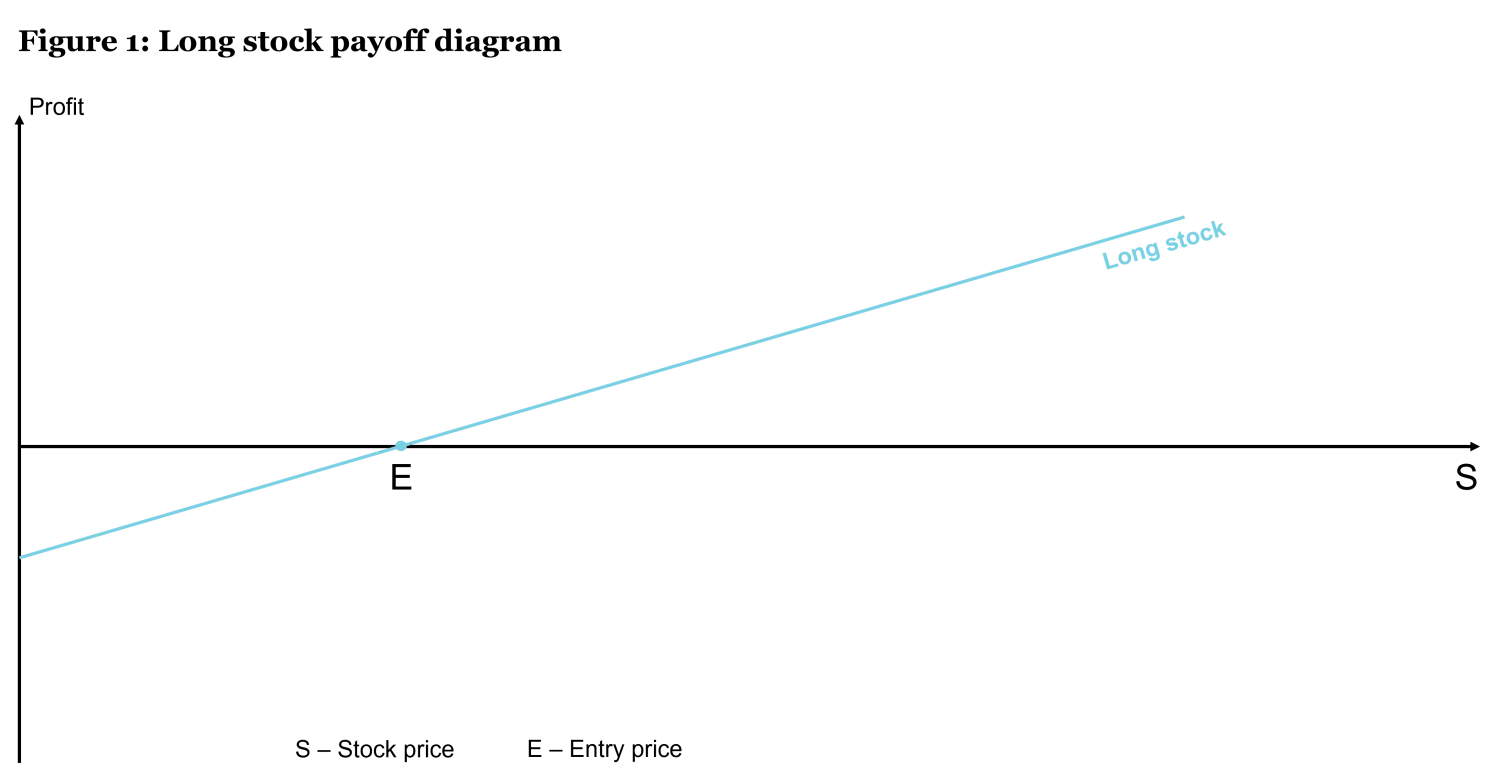

Figure 1 shows the payoff diagram of a long stock position. The y-axis represents the investor profit as a function of the stock price, which is represented on the x-axis. The payoff profile (a straight line in this case) intersects the x-axis (corresponding to the zero-payoff case) at E, the price at which the investor bought the stock. The potential profit is unlimited as the stock price rises, while the potential loss is limited to the initial investment E (the worst the investor can lose is E).

In certain situations, investors might want to sell call options as an add-on to their equity holdings. Options are financial contracts that give the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a predetermined price (the strike price) at a certain moment in time (the expiry date) 1.

While the call option gives the owner the right to exercise, it gives the seller the obligation to sell. It is often said that the seller of a call option is "short" the option. The seller of the option receives an option premium in exchange for taking the obligation in the contract. As a rule of thumb, the farther away the expiration date and the more volatile the market, the bigger the premium received.

Consider the example of a call option on a certain stock with strike price K. At expiry, if the stock price S>K, the owner of the call option has the right to buy the stock at a price K from the seller of the option contract. Since S is greater than K, the call option owner will most likely do that. Why? Because the option owner can buy the stock at K and resell it immediately in the market for S, thus pocketing the profit S-K.

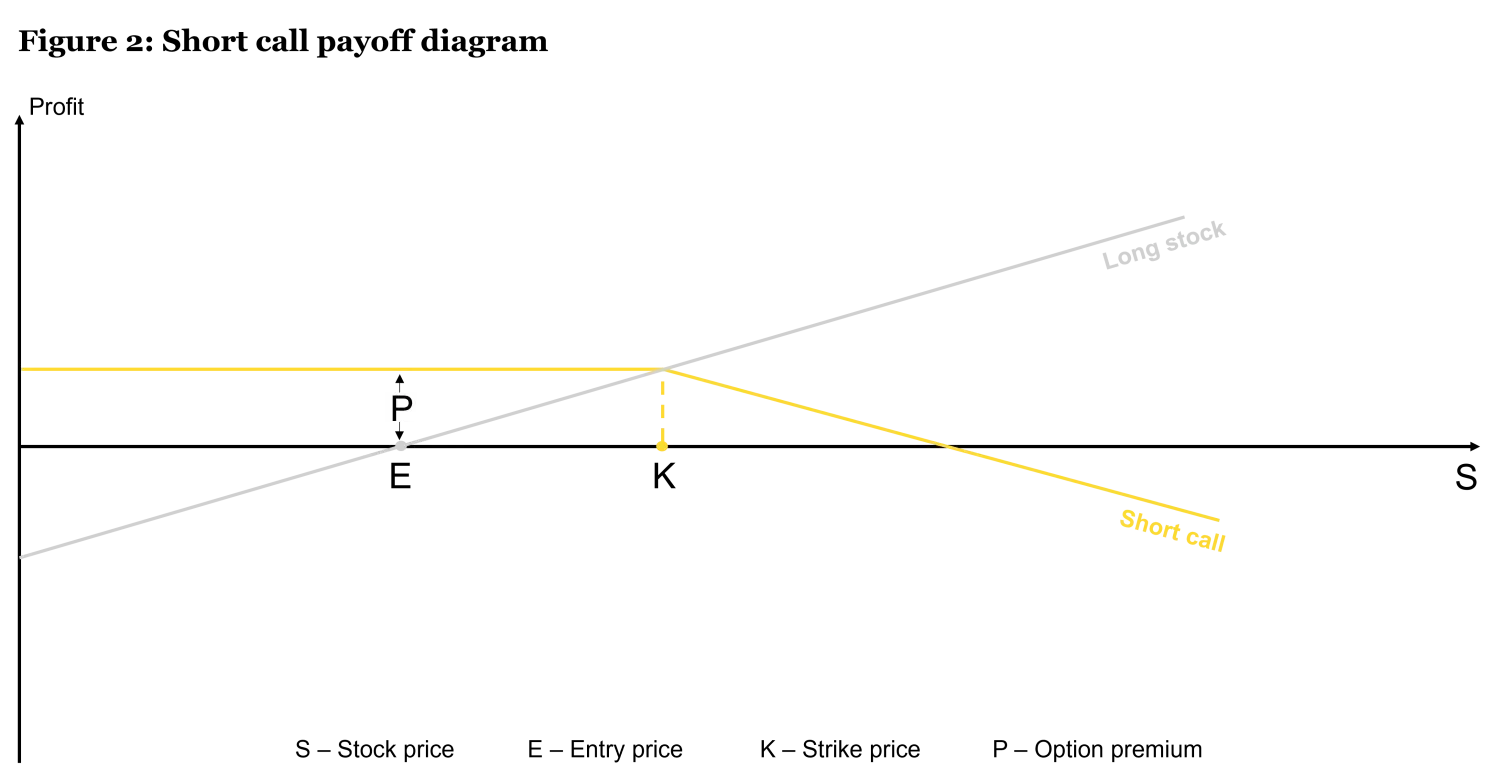

Figure 2 shows the payoff diagram at expiry for an investor who is short a call option with strike price K. In such a situation, the potential profit is limited to the premium, while the potential loss is unlimited, since (at least theoretically) the stock price can rise above the strike price ad infinitum. If the price at expiry is S and this is greater than K, the investor will still have to sell the stock to the owner of the option at price K.

But, as the investor does not hold the stock at expiry, they will need to buy it in the market (spending S) in order to sell it to the call option owner at K, making a loss in the process. As soon as S is greater than K+Pr, (where Pr is the premium collected via the sale of the call option) the investor will lose money (i.e., negative payoff) on their short call position. Since the investor does not hold the stock prior to the sale of the call options, this position is often called "naked" (as opposed to a "covered position", as it will be discussed next).

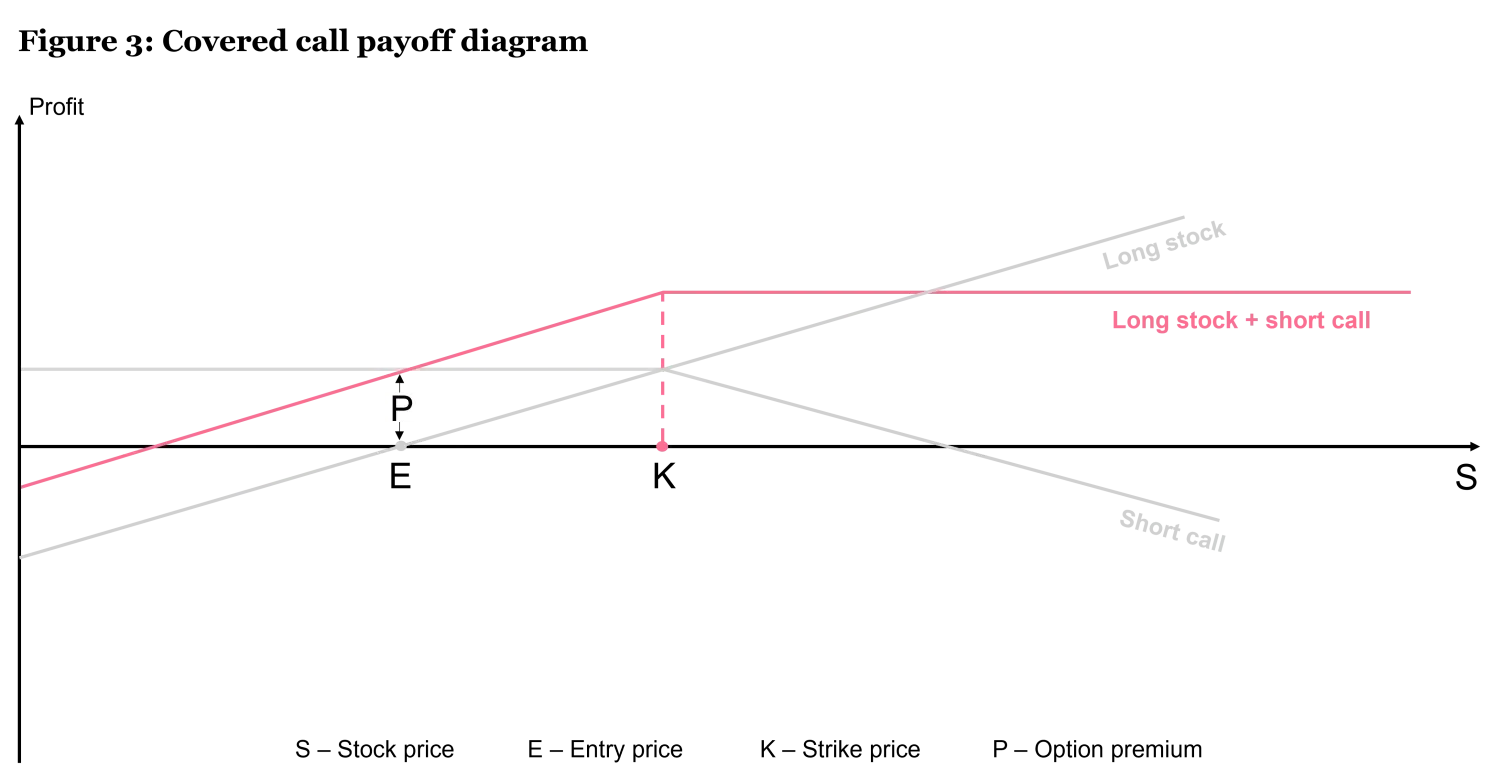

Now consider an investor who is long the stock and short an option on the same stock (a “covered” position). The investor’s payoff profile – represented in figure 3 – will be the sum of those represented in figures 1 and 2. The main difference between the situations depicted in figures 3 and 2 is that – upon exercise of the option – the investor does not have to buy the stock in the market (in order to deliver it to the owner of the call option). This is because the investor owns the stock already. That is why we call this setup “covered”.

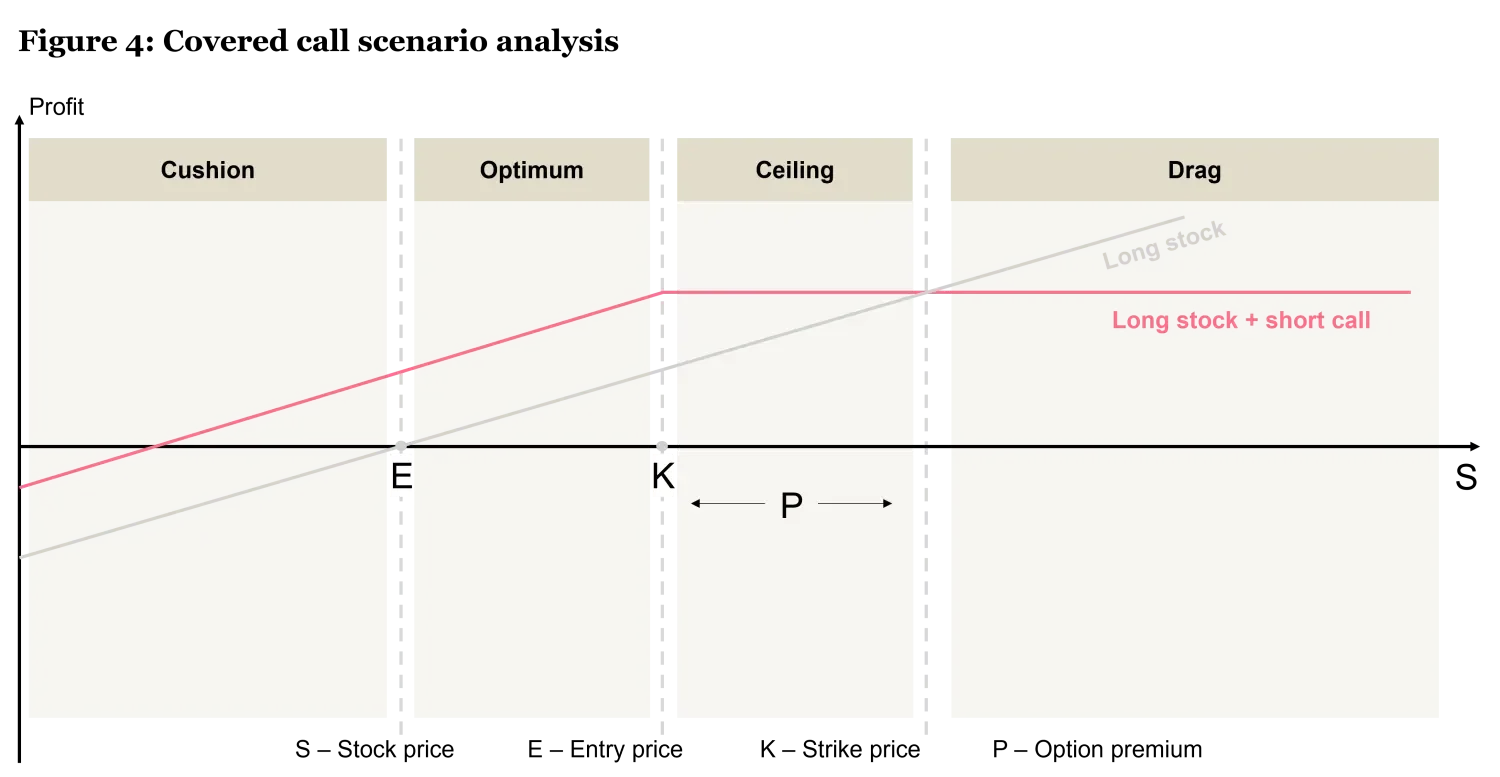

We can categorize the possible outcomes for our fictitious investor as a function of the stock price at expiry as depicted in figure 4. If S<E (i.e., the stock at expiry is worth less than the price at which it was purchased), the investor will be glad to have sold a call option on it, because the option premium Pr will partially compensate for the losses on the stock. We call this region “cushion”. Note that the option partial compensation for the losses on the stock is limited. As soon as the stock price falls below E-Pr, the investor will incur a loss.

If E<S<K (which we call “optimum”), the investor will retain the stock at expiry (since the call won’t be exercised). The investor was better off having sold the call option than not, since they got the extra profit coming from the premium collected via the sale of the option.

If K<S<K+Pr (which we call “ceiling”), the investor will come out with a profit and will have been better off with the call option than not. This is because, even though the option will be exercised (and therefore the investor will have to sell the stock at a price K), the cash collected plus premium (K+Pr) is still higher than the value of the stock at expiry S. Therefore, the total payoff is K-E+Pr.

Figure 4 introduces another region called “drag”, even though there is no difference with respect to the investor payoff when compared to “ceiling”. Why? It is to underscore the fact that, within “drag”, the investor would have been better off not having sold the call option at all. Within “drag”, the investor payoff is K-E+Pr (like in “ceiling”). But if the investor had not sold the call option (and thus would have retained the stock at expiry), their payoff would have been S-E. Since S>K+Pr, the investor would have been better off without the call option.

What’s the benefit then?

If markets do not rise strongly and permanently, a covered call strategy offers a compelling way to play equity allocations for two reasons.

First, it allows investors to extract an “extra” source of income via the sale of call options on the underlying equity portfolio (see “optimum”). Second, the covered call strategy allows some protection (“cushion”) during market downturns.

Also, note that the “extra” source of income provided by covered call strategies materializes in the form of a cash payout (the option premium is paid in cash). Hence, the strategy is particularly attractive for investors seeking income from their investments.

What are the drawbacks?

The main drawback with covered call strategies is that, should markets rise vigorously and permanently, an investor would be better off with a long stock position (as in the “drag” region of figure 4).

Moreover, while not a drawback, it is important to relativize the benefits offered by the “cushion” region. A covered call strategy will protect the owner of a stock portfolio only for the buffer offered by the option premium sold, but no more.

Up next:

As described in this article, a covered call strategy will do less well than a long equity position if markets trend upward vigorously and constantly.

Therefore, such strategies are typically implemented in markets where the investor only expects a moderate increase in equity markets, or sideways markets.

In the next article of this series, we argue that equity markets may offer, in the course of the next decade, the right setup for investors to profit from a covered call strategy (the “why”).

1. This is true for European options, not American options. Throughout the paper, when we refer to options, we mean European options.