2024 according to our Fixed Income Boutique

Fixed Income Boutique

Key takeaways

- We think 2024 will be the year of the bond after the foundation for it was laid in November 2023. With global interest rates likely having peaked in October and the global economy slowing, we expect monetary policy easing in developed markets to start by mid-2024.

- Recent data supports the market consensus for a soft landing. And if the consensus is wrong, a recession is likely to be mild. Either outcome would be positive for global credit and emerging markets, as they benefit from lower US Treasury rates. A mild recession isn’t a crisis, and that matters for spreads.

- Even after the November and December rally, real interest rates remain high at around 1.7 percent in the US. These high real rates are cyclical, not structural, and therefore the current environment presents medium-term investors with a good entry opportunity into global fixed income.

- The eurozone economy is currently weaker than the US, but inflation dynamics also appear more benign, favoring duration bets in the currency union. The recession risk in Europe is higher than in the US, but this is already reflected in valuations, where credit spreads have been above historical averages since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- We believe global credit is a good place to be, even for investors who may be unconvinced about the soft-landing consensus. Developed IG companies have built large buffers that would allow them to withstand a recession without major spread widening.

- In our view, global high-yield and emerging markets are poised to deliver double-digit returns in our soft-landing baseline and offer such a high carry cushion that it would take a very large negative shock to end up with negative returns.

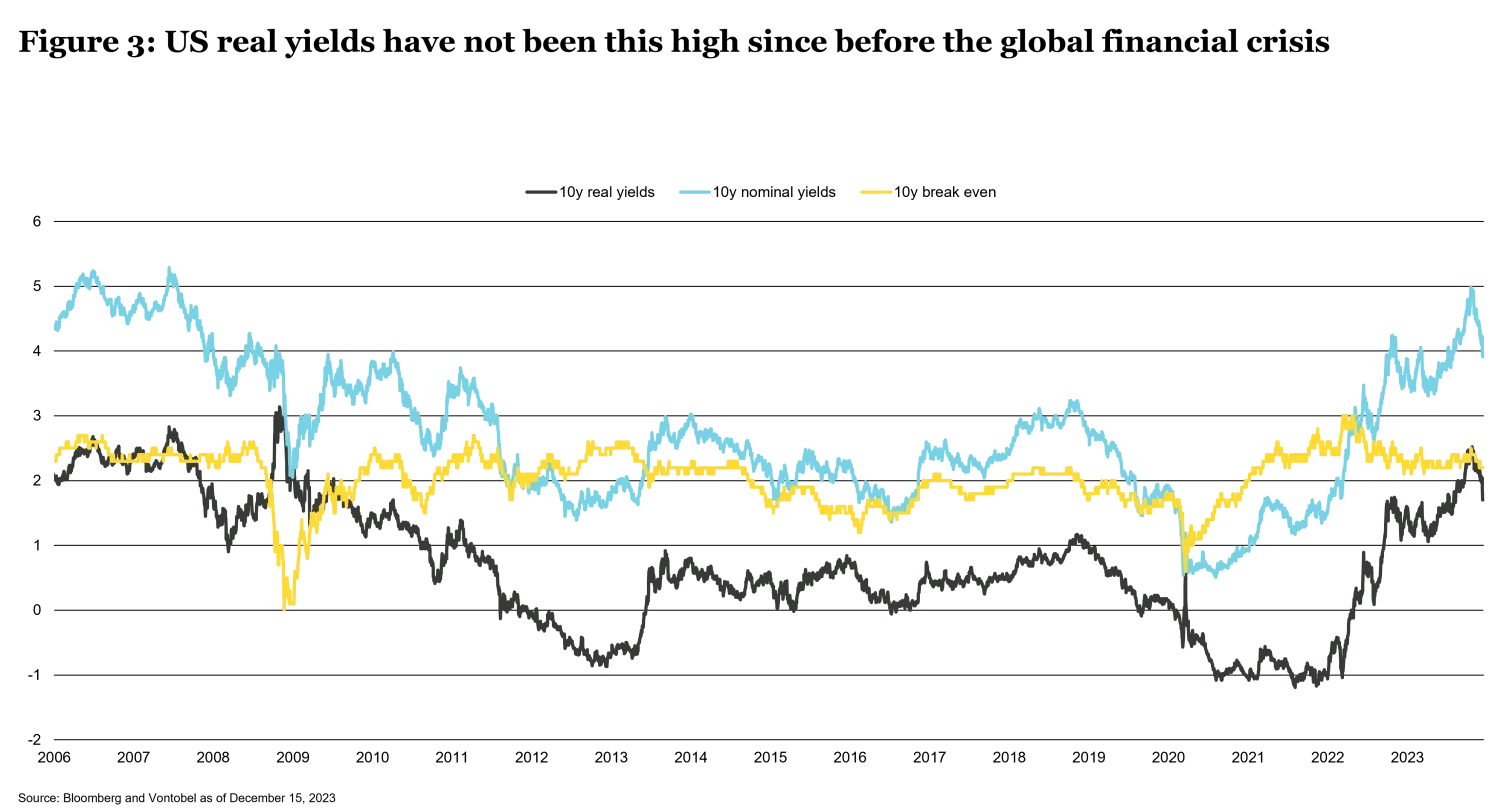

Many predicted that 2023 would be the year of the bond, but this proved premature. Central banks hiked interest rates sharply in 2022, but not enough to tame real interest rates in developed markets to sufficiently restrictive levels to assure a path to reaching inflation targets. Consequently, monetary authorities continued raising interest rates last year, bringing real rates to their highest levels since 2007. While far from complete, a disinflationary phase is now at an advanced stage, and it’s realistic to assume inflation will normalize over the next two years across most geographies. It’s not “higher for longer” anymore, but rather “high for a little while.”

Better late than never. We think 2024 will now be the year of the bond, a trend that actually began in November 2023. With global interest rates likely to have peaked in October and the global economy slowing, monetary policy easing in developed markets is likely to start by mid-2024.

This outlook provides an overview of what we expect to see globally in the fixed income world in 2024, then focuses specifically on global credit and emerging markets (EM).

Global macro outlook

Recent data supports the market consensus for a soft landing. And, if there is a recession, it will likely be mild. Either outcome (no recession or mild recession) would be positive for global credit and EM, as they benefit from lower US Treasury rates. Spreads are seen as remaining relatively unchanged unless a crisis causes a hard landing.

US economic resilience won’t continue in 2024, but the economy won’t fall into a crevasse either. The latest non-farm payroll gains and inflation, and recent survey data confirms an ongoing economic slowdown but no imminent recession. These indicators and lower short-term commodity prices reinforce our view of a US economy in orderly deceleration, gradual disinflation, and a US Federal Reserve (Fed) that’s done ratcheting up rates.

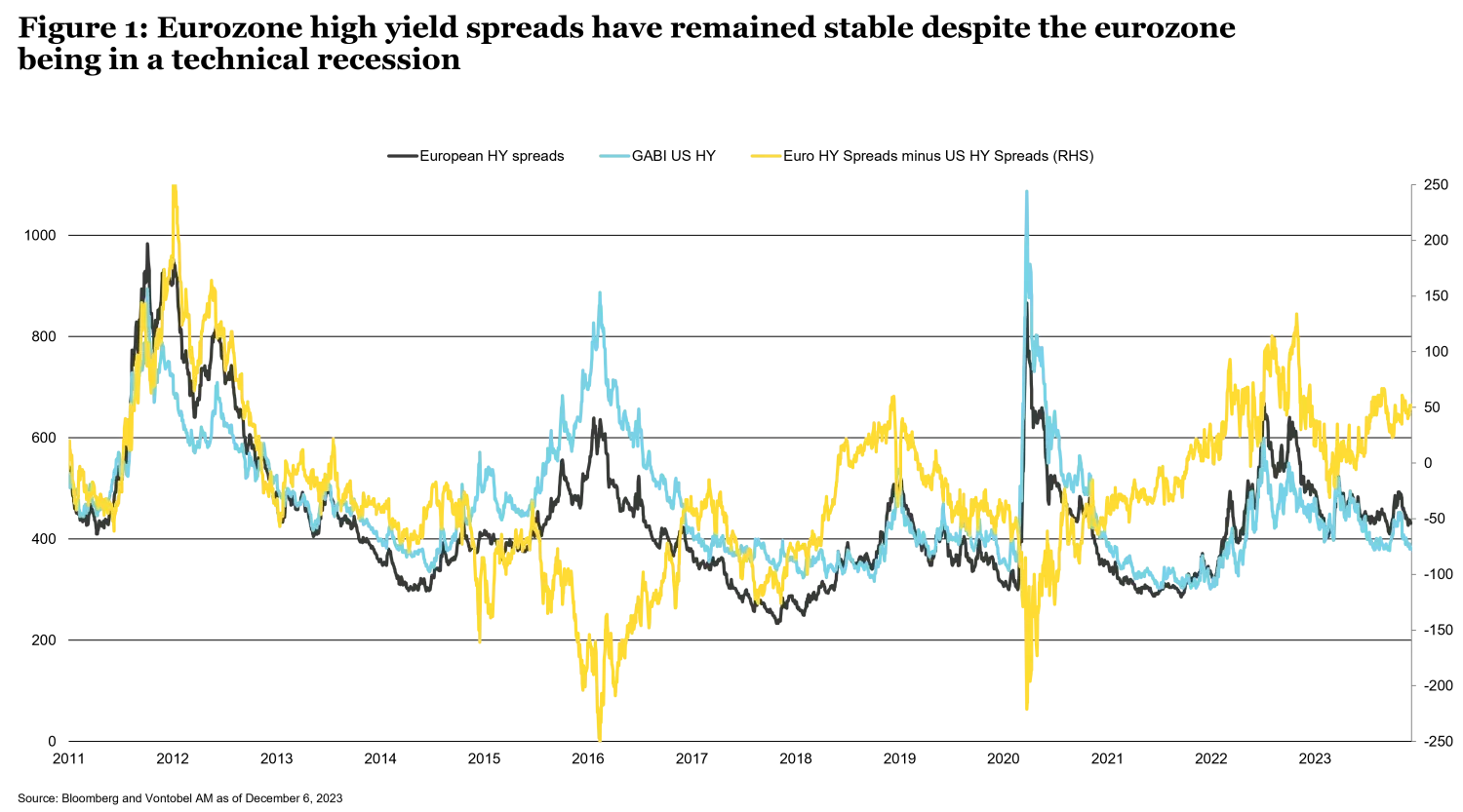

A mild recession isn’t a crisis, and that matters for spreads. The US risks falling into recession if the Fed keeps its policy too tight for too long, but what’s currently happening in the eurozone supports our view. GDP contracted 0.1 percent in the third quarter, and near-zero growth is likely to continue for the short term. Still, eurozone high yield spreads haven’t widened (see figure 1). We think a similar outcome in the US is possible, with well-behaved spreads in both the US high-yield market and EM being a very plausible scenario.

Is the European Central Bank (ECB) waiting too long for a second time? The eurozone economy may already be in a mild technical recession, with growth close enough to zero, no crisis in sight, and easing price pressures. Producer inflation fell 12.2 percent year-on-year since their September 2022 peak, and while core prices increased by an above-target 3.6 percent in November on a yearly comparison, they rose at a more moderate 1.4 percent annualized rate over the last three months.

The economy in the eurozone is weaker than that in the US, and inflation momentum is slower, implying a faster convergence to the 2 percent target in the single-currency area and justifying the ECB cutting rates before the Fed. However, the ECB is risking a second policy mistake during this inflation cycle. Fearing excessive wage growth, recent statements from ECB officials suggest they could wait until the conclusion of spring wage negotiations before changing course. After first hiking too late and potentially too high, waiting to see where wages wind up puts it at risk of being tardy in climbing down from the current stance. The result could be a more significant recession. This is clearly an unfavorable scenario for European credit spreads, but favorable for duration bets in the eurozone, which did not rally as strongly as US Treasuries in November. Although not our baseline view, we assign this risk a higher probability than a deep US recession.

In economics, if you wait long enough, your forecast may eventually come true. The Fed’s much maligned “inflation is transitory” mantra ended up being somewhat correct after all, with Chairman Jerome Powell failing to foresee the transition lasting three to four years instead of a few quarters. The disinflationary process has been global, gradual, and orderly, with no deep recessions, crises, or systemic debt defaults in sight.

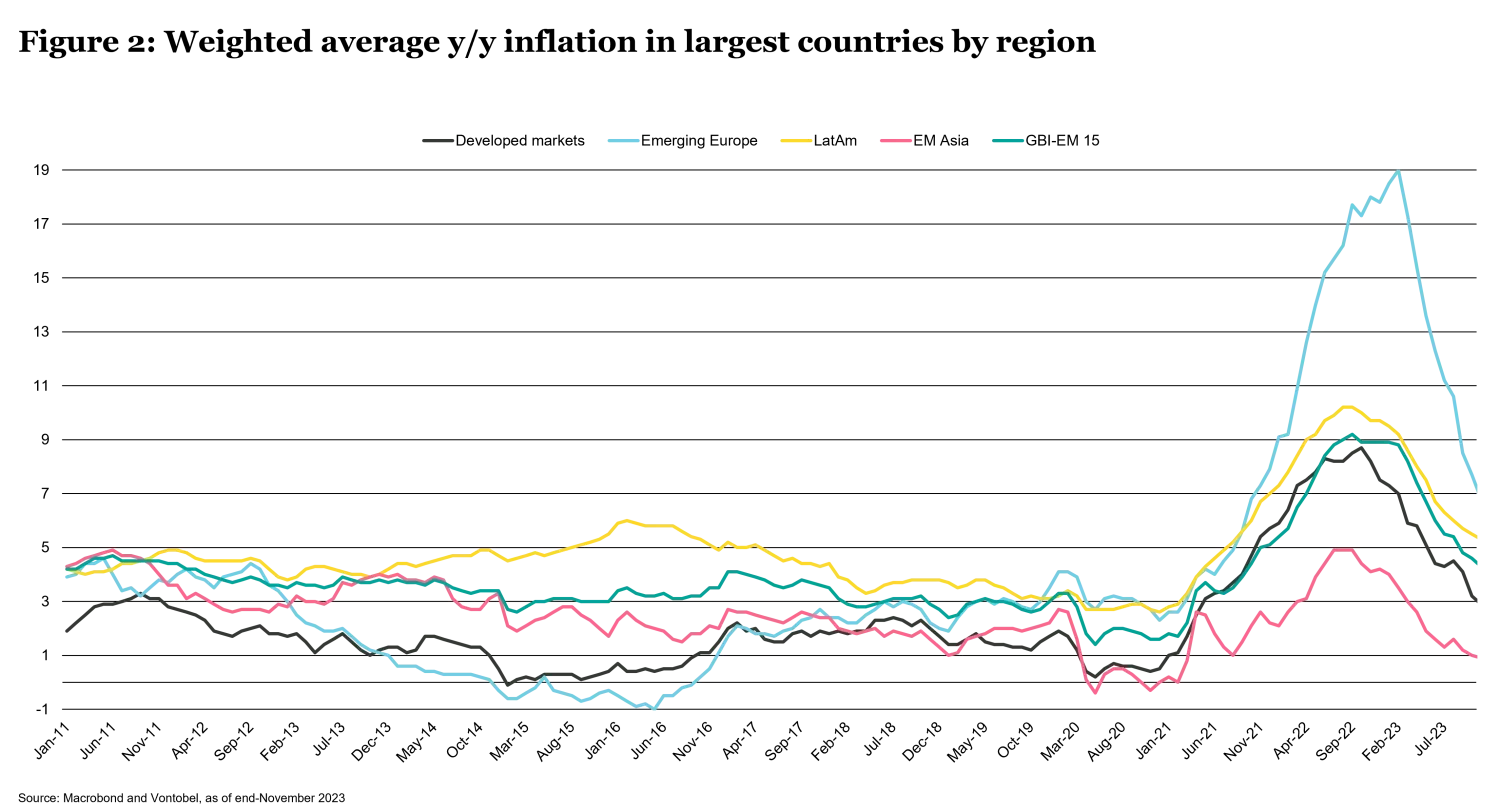

Inflation in Latin America has been declining in tandem with developed markets (see figure 2). In Eastern Europe, it fell significantly this year after peaking at extraordinarily high levels in 2022 due to high reliance on imported gas. In Asia, price gains are currently lower than pre-pandemic levels, driven by China’s weak economic recovery and moderate commodity prices. Although EM central banks have begun cutting rates, we think monetary policy across the regions will remain sufficiently restrictive for this to continue in 2024. Barring a strong recession next year, it will take until 2025 for most countries to get inflation back to target. A few EM countries are notably ahead of the cycle and will attain their goals in 2024.

US 10-year Treasury yields are trading around 3.9 percent, while market inflation expectations are around 2.2 percent, translating into long-term real interest rates of 1.7 percent (see figure 3). While the investor entry point isn’t as favorable as in October, when nominal 10-year Treasury yields peaked at nearly 5 percent, such high real interest rates haven’t been seen since 2008. Real equilibrium interest rates are governed by potential economic growth, demographics, savings, and investment behavior. Potential growth estimates have been trending downwards across developed markets for over a decade, and all mainstream forecasts suggest this trend is likely to continue, which does not support real rates at 15-year highs over the medium term.

Our societies are also ageing, with working-age population growth predicted to slow further. As a result, this should drive real rates lower. Finally, savings rates have been depressed on the back of pandemic fiscal stimuli as well as high inflation, spiking the anticipation of consumption. With inflation down to 3 percent, declining from a peak of over 9 percent in 2022, and savings being rewarded more handsomely, this is unlikely to remain the case.

The currently elevated real interest rates appear to be driven by tight monetary policy and uncertainty about the pace of decelerating inflation, both of which are cyclical, not structural. This is why we think real interest rates are unlikely to stay this high. They may not return to pre-pandemic levels of zero or even negative, but real rates will likely go down from here, providing a good fixed income entry opportunity for the medium term.

Global credit is well-positioned to gain from a soft landing and contained risks

Our baseline scenario for a soft economic landing and elevated real yields provides investors with a good medium-term opportunity in global credit markets. Historically high starting yields provide attractive risk-adjusted income and capital appreciation. Moreover, even if a significant recession materializes, the fundamentals of investment-grade companies are sufficiently solid and should withstand a more severe downturn without spreads widening dramatically. Starting positions matter, and conditions today are far better than at the beginning of the pandemic or during the global financial crisis. Global credit is a good place to be, even for investors who may be unconvinced of a soft landing.

Duration will play a greater than usual role for global credit portfolios. With yields at multi-year highs, investors have prospects for much better forward returns with global corporate bonds. Slowing but positive economic growth is often the ideal environment for companies to exercise cautious balance sheet management. While a few company outlooks were mixed recently, credit metrics are seen stabilizing, with reasonable earnings expected for the coming quarters from the increased likelihood of a soft landing.

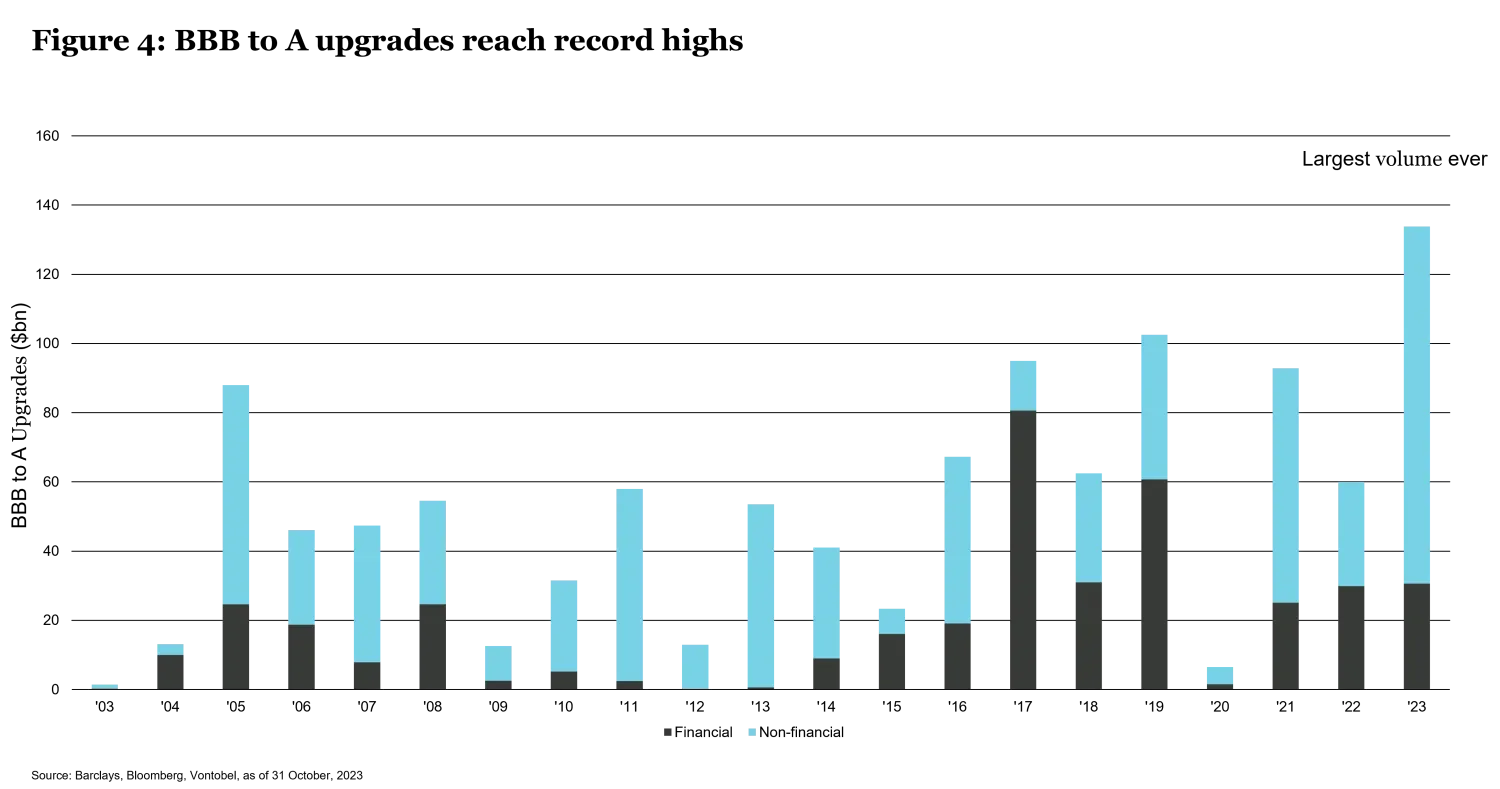

We see this reflected in the positive trend for credit rating upgrades. During 2023, BBB-rated companies benefitted the most, with upgrades from BBB to A at a record high (see figure 4). We expect this trend to continue into 2024 in our soft-landing case.We see this reflected in the positive trend for credit rating upgrades. During 2023, BBB-rated companies benefitted the most, with upgrades from BBB to A at a record high (see figure 4). We expect this trend to continue into 2024 in our soft-landing case.

Euro corporates are well positioned to benefit from the current outlook. Inflation momentum slowing more significantly in the eurozone is translating into more bullish duration bets for euro-denominated bonds than for their dollar counterparts. While we acknowledge the risk of the ECB maintaining current rates for too long, any economic damage would end up translating into lower long-term inflation and deeper rate cuts than markets are pricing in for the second half of 2024.

Labor markets and the services sector have proven resilient, remaining relatively unaffected by ongoing industrial sector contraction, with negotiated wages growing in real terms, providing support for consumption and services. Europe has a weaker economy in comparison to the US, and we think relative valuations reflect this. Contrary to the US, European spreads are currently wider than their long-term averages, implying additional risks are already priced in with good potential for spread tightening should our soft-landing scenario play out.

Our credit team favors a barbell strategy for European credit, with a preference for senior banks and less cyclical industrial sectors such as telecoms, utilities, and transportation. On the flip side, higher beta-subordinated structures haven’t fully recovered from the shock demise of Credit Suisse. European banks should be able to sustain their strong credit quality and capitalization next year despite slowing growth. Less cyclical industrial sectors look better in value and quality than their cyclical counterparts, where spread premiums remain low relative to the economic slowdown.

Globally, slowing growth lends a favorable backdrop for high-yield bonds. The forward-looking return potential looks strong for developed markets, given their starting yield level of almost 8 percent. We see potential for generating equity-like returns with much lower volatility in our soft-landing scenario. We also see more limited spread-widening risks than in previous late-stage cycles if major risks materialize due to a more significant recession. The starting yield is so high that there would need to be a very large negative shock or crisis to fully erode expected carry returns in 2024.

Default rates running at 2 percent for developed market high-yield bonds during the last 12 months are exceptionally low for this stage of the cycle. As the global economic slowdown starts to bite, we see default rates trending to 3-4 percent in the next 12 months. This is well below previous down cycle peaks for three reasons:

- Overall high-yield credit quality improved over time. The BB segment currently comprises 57 percent of the global high-yield universe, up from 48 percent a decade ago, as fallen angels entered the mix, while the single B and CCC segments shrank.

- The US energy sector contributed half of US high-yield defaults in the last two default cycles. With relatively high oil prices, energy companies are generating ample free cash flow, indicating defaults in the US HY energy sector will likely be low this time.

- Corporate balance sheets are in good shape overall at this stage of the credit cycle.

The bond supply and demand picture is favorable for all global credit, particularly for high-yield and EM. Elevated financing costs led companies worldwide to postpone refinancing or seek alternative funding when possible, resulting in a lower than usual bond supply. This is particularly the case for high-yield and EM issuers because many of these companies and sovereigns have been facing prohibitively high borrowing costs and have made the most effort to postpone issuances.

The face value of the US high-yield bond market shrank from USD 1.5 trillion to USD 1.3 trillion, while the European high-yield bond market contracted from EUR 610 billion to EUR 490 billion in the last two years. Higher all-in yields have led companies to refinance debt with alternative instruments or simply pay down debt with cash, providing fundamental and technical support to the asset class.

High borrowing costs deterred high-grade companies from going on a borrowing spree. Even for investment-grade corporates, we expect net issuance to slowdown in 2024 until global rates decline more significantly. Investor appetite should remain high, driven by “yield-buyers” starting to lock in once-in-a-generation yields and coupons. In European credit markets, we expect the net supply of non-financials to remain limited and be supportive of credit spreads that are still above their long run averages.

EM are poised to deliver high single-digit or double-digit returns in 2024

Our global soft-landing baseline would be a positive outcome for EM fixed income for several reasons, for both hard and local currency debt. Sovereign and corporate hard-currency issuers would see their yields decline in parallel with US Treasury rates and potentially experience some spread compression absent a recession. In the case of a mild US recession, we think EM spreads will remain stable, as we’ve seen with European high-yield spreads amid ongoing economic contraction but no crisis in the eurozone.

The expected economic slowdown in developed markets is also likely to affect many large EM in 2024 as the delayed effects of tight monetary policy continue to work their way through the system. With an investment universe of 80 countries, there are exceptions, and a few countries, such as India, will be experiencing relatively fast growth. In contrast to developed markets, where rate cuts are expected to begin around mid-2024, many EM central banks have been cutting rates for several months. This is particularly true in Latin America and Eastern Europe, which started hiking earlier and have seen the effects of tight monetary policy on their economies and inflation dynamics. We see EM central banks continuing their gradual easing cycle through 2024, which should support local currency bonds and ease domestic financing conditions for corporate issuers, which can also refinance in their domestic debt markets.

Let’s take an early hiker like Brazil as an example. The South American country started hiking rates aggressively well ahead of everyone else in March 2021 and began cutting rates in August 2023, we can already see the domestic market reopening for many issuers and reducing refinancing risks. We think this dynamic will expand to several major EM markets next year, well ahead of developed markets. Corporates and sovereigns in large EM countries with well-developed domestic financial systems will benefit from this trend of easier domestic financing conditions.

Some may worry that with EM central banks cutting rates ahead of the Fed, EM currencies will suffer and sour sentiment towards the asset class. This was the case during the Fed’s 2018 hiking cycle, when several EM central banks refused to follow the Fed. However, EM local-currency bonds have delivered returns of almost 10 percent year-to-date showing that EM central banks don’t need to move in lockstep with the Fed for the asset class to perform well. In 2018, many EMs had low inflation and were unconcerned about their exchange rate stability, hence their refusal to follow the Fed. Those EM countries that hiked aggressively during 2021 and 2022 are cutting rates, albeit at a cautious pace. With inflation still above target, they’re aware that cutting aggressively would result in FX pressures. We expect EM central bank cautiousness to remain at play, at least until the Fed starts cutting, which should remain supportive of EM local-currency bonds.

Investment-grade issuers are usually seen as the market segment benefiting the most from declining rates in developed markets given their higher correlation with US Treasuries. However, with lower US Treasury yields, many high-yield issuers are likely to regain market access over the next twelve months, creating a virtuous cycle as the fear of default is taken off the table. We remain positive on a selected group of high-yielders with low short-term default risk.

The default cycle in EM has been running years ahead of developed markets since the pandemic, and not in a good way until now. Defaults typically occur in the early stages of a crisis, when companies and sovereigns see their revenues fall dramatically. Covid and the war in Ukraine sparked severe crises in many countries, resulting in high default rates in the last four years. For those countries that managed to avoid default so far, it makes no sense to do it now that the crisis is over.

In the case of sovereigns, apart from Ukraine, which is expected to go ahead with debt restructuring following a two-year standstill agreed to in 2022, Ethiopia is the only sovereign expected to default and this is already in the price. This compares favorably with six sovereign defaults in 2020 and five in 2022, representing a return to the historical norm of zero to two defaults per year. The domino effect of EM sovereign defaults some analysts expected failed to materialize, and these fears are now behind us. EM corporate defaults are also expected to decline going forward now that most troubled Chinese property developers have already defaulted, the Russia and Ukraine-related defaults are behind us, financial conditions in large EMs are already starting to ease, which facilitates domestic refinancing, and lower US Treasury yields should help high-yield companies regain market access.

If US Treasury yields, EM spreads, and the dollar remain constant, the yields of 7.1 percent for hard-currency sovereigns, 6.2 percent for EM corporates, and 5.3 percent for EM local currency provide decent guidance for future returns. But we are more constructive than that. In the current environment, it’s only reasonable to expect lower US Treasury yields and EM local rates over the next 12 months. If we assume US and EM rates fall by 100bps while spreads and the dollar remain constant, we would see total returns of almost 14 percent for EM hard-currency sovereigns, more than 10 percent for corporates, given the lower duration, and almost 15 percent for local-currency bonds.

Local EM bonds could do even better in a weakening dollar environment, which isn’t unusual during a Fed easing cycle. Sovereign EM and hard currency issues could see tighter high-yield spreads if our lower default rate scenario plays out, further compounding returns. All EM fixed income experienced outflows of USD 120 billion in the last two years, and if only some of this money were to return, we could see further spread compression and EM FX gains. As with developed market high-yield, the main risk would be the materialization of a more severe downturn that could result in spread widening. Here too, the carry cushion is so high that it would take a very large negative shock to end up with negative returns. In a severe recession scenario where US Treasury yields may fall by 200bps, for example, one would need EM sovereign spreads to widen by more than 300bps and EM corporate spreads by 350bps to end up with negative returns. Such dramatic spread widening episodes occurred during the global financial crisis and the covid pandemic but proved to be rather brief.

Important Information:

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Information herein does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status or investment horizon. All investing involves risks including possible loss of principal.

Any projections or forward-looking statements regarding future events or the financial performance of countries, markets and/or investments are based on a variety of estimates and assumptions. There can be no assurance that the assumptions made in connection with the projections will prove accurate, and actual results may differ materially. The inclusion of forecasts should not be regarded as an indication that Vontobel considers the projections to be a reliable prediction of future events and should not be relied upon as such. Vontobel reserves the right to make changes and corrections to the information and opinions expressed herein at any time, without notice.