What we don’t know: the gap between AI hype and economic reality

Quality Growth Boutique

Key takeaways

- AI is a transformative technology, although its long-term impact remains uncertain. Historically, investment returns do not always match the hype of innovation.

- Unlike recent advancements in software and the Internet, today’s AI cycle is marked by the capital-intensive nature of building datacenters and meeting their substantial energy demands.

- AI investments must become self-financing and deliver adequate returns to be sustainable. While the “big four” hyperscalers generate sufficient free cash flow to support large-scale investments, many large LLM developers rely heavily on debt and equity financing.

- Business models for AI applications remain undefined, making it challenging to forecast revenues. The rapid depreciation of AI chips raises questions about whether the big players’ margins will improve.

- We seek to identify long-term growth opportunities in travel, entertainment, and luxury goods, which are less reliant on AI.

- History demonstrates that stock prices invariably follow earnings growth. We seek to invest in what we know: companies that we believe have predictable, sustainable earnings growth.

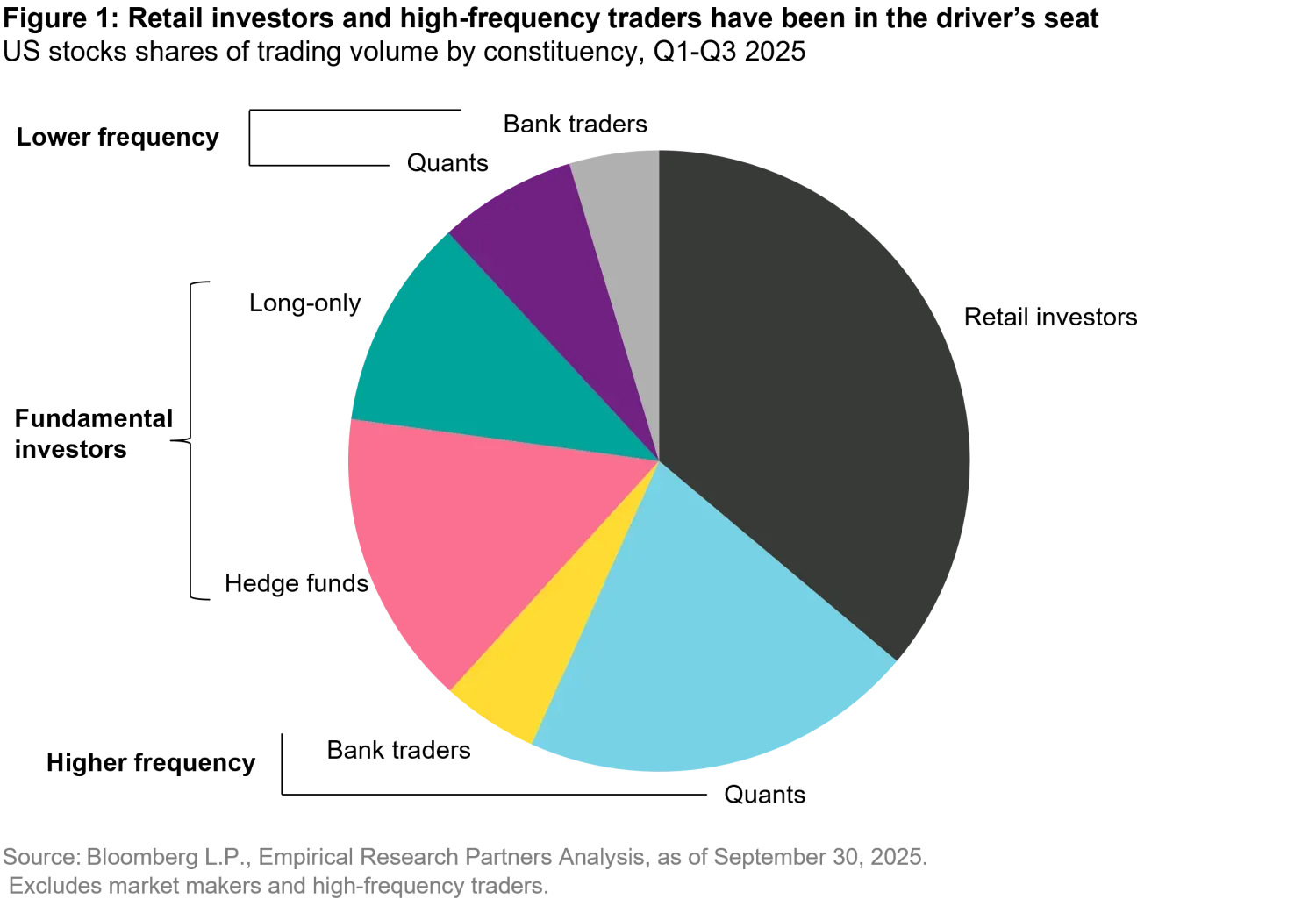

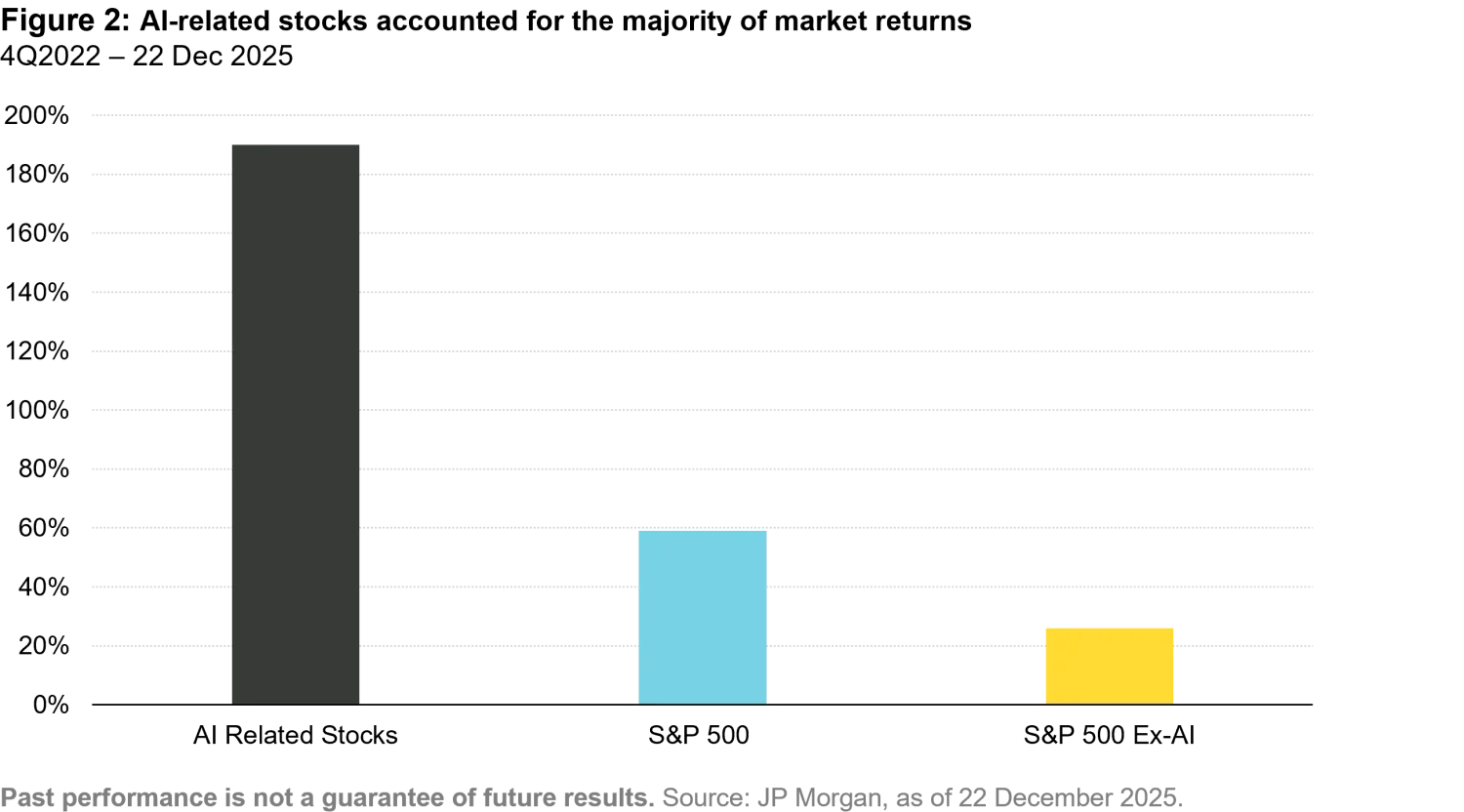

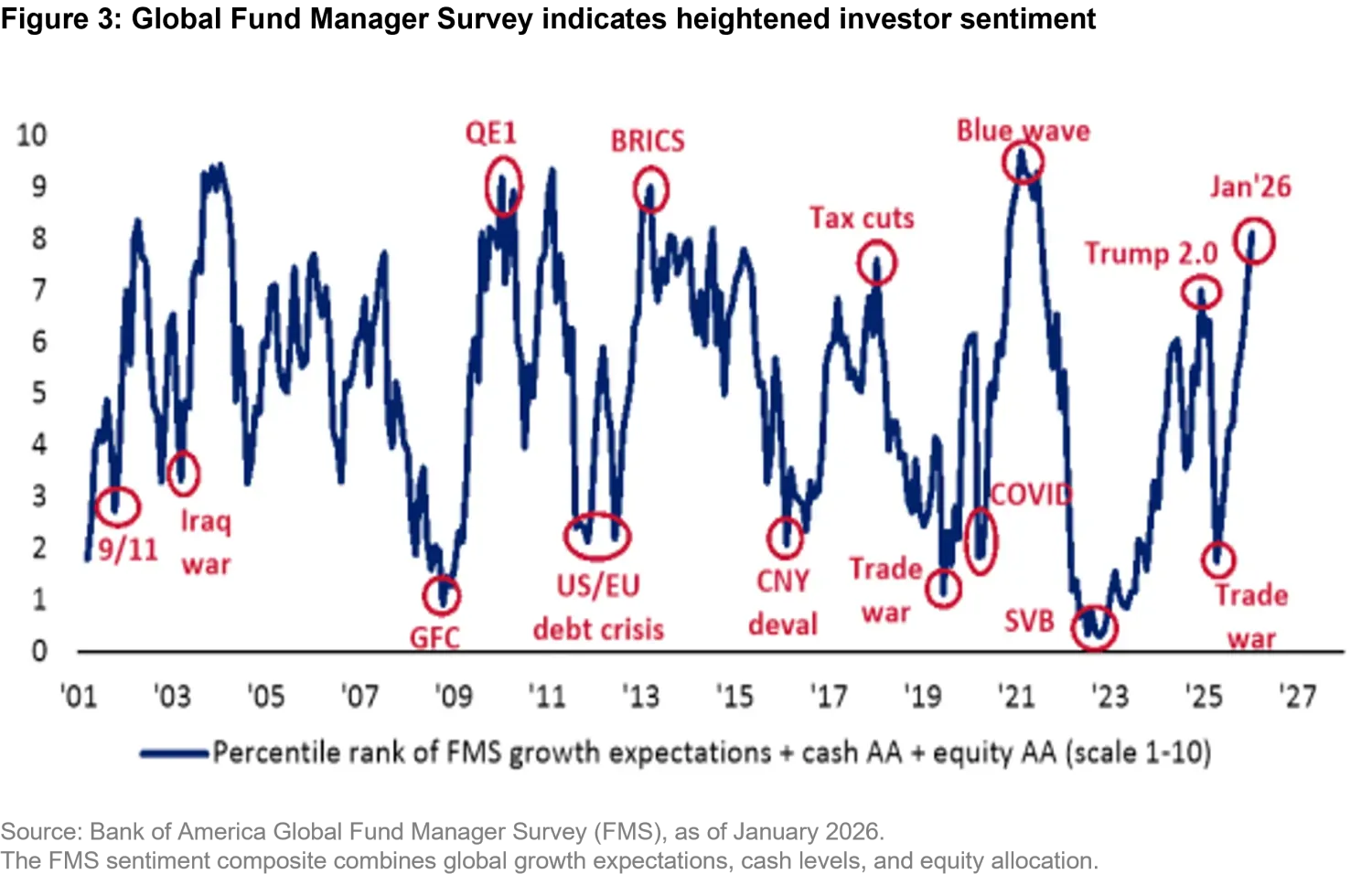

Many centuries ago, Socrates argued that wisdom begins with the admission of ignorance. Today’s investors have little patience for such platitudes (Figure 1). Since the launch of Chat GPT in late 2022, just 42 AI-related stocks accounted for more than half of market returns (Figure 2). Reflecting this enthusiasm, Bank of America’s global fund manager survey reveals that global investor sentiment is now at its most bullish level since July 2021 (Figure 3).

Beyond AI, developments in the global economy and geopolitics warrant concern

The post-war, US-led Western democratic order is increasingly being put to the test. Over the past year, the US administration has strained the global trading system that was in place since 2001, when China joined the WTO. Through a convoluted approach to tariffs, the US has not only driven a wedge between itself and China but also created tensions with several of its traditional Western allies. Even once-sacrosanct beliefs, such as the independence of the Federal Reserve, an essential anchor of global financial stability, are now being openly questioned.

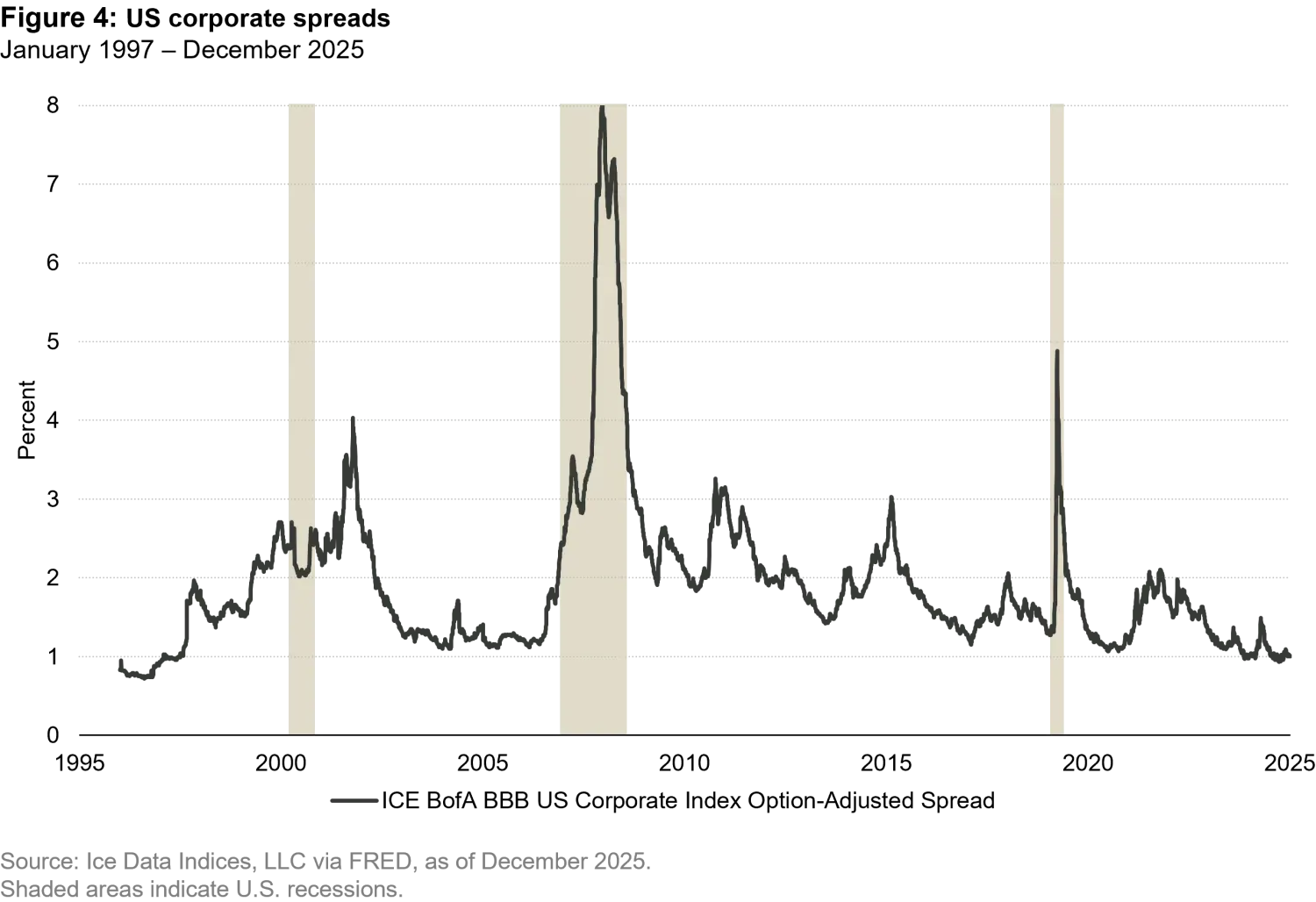

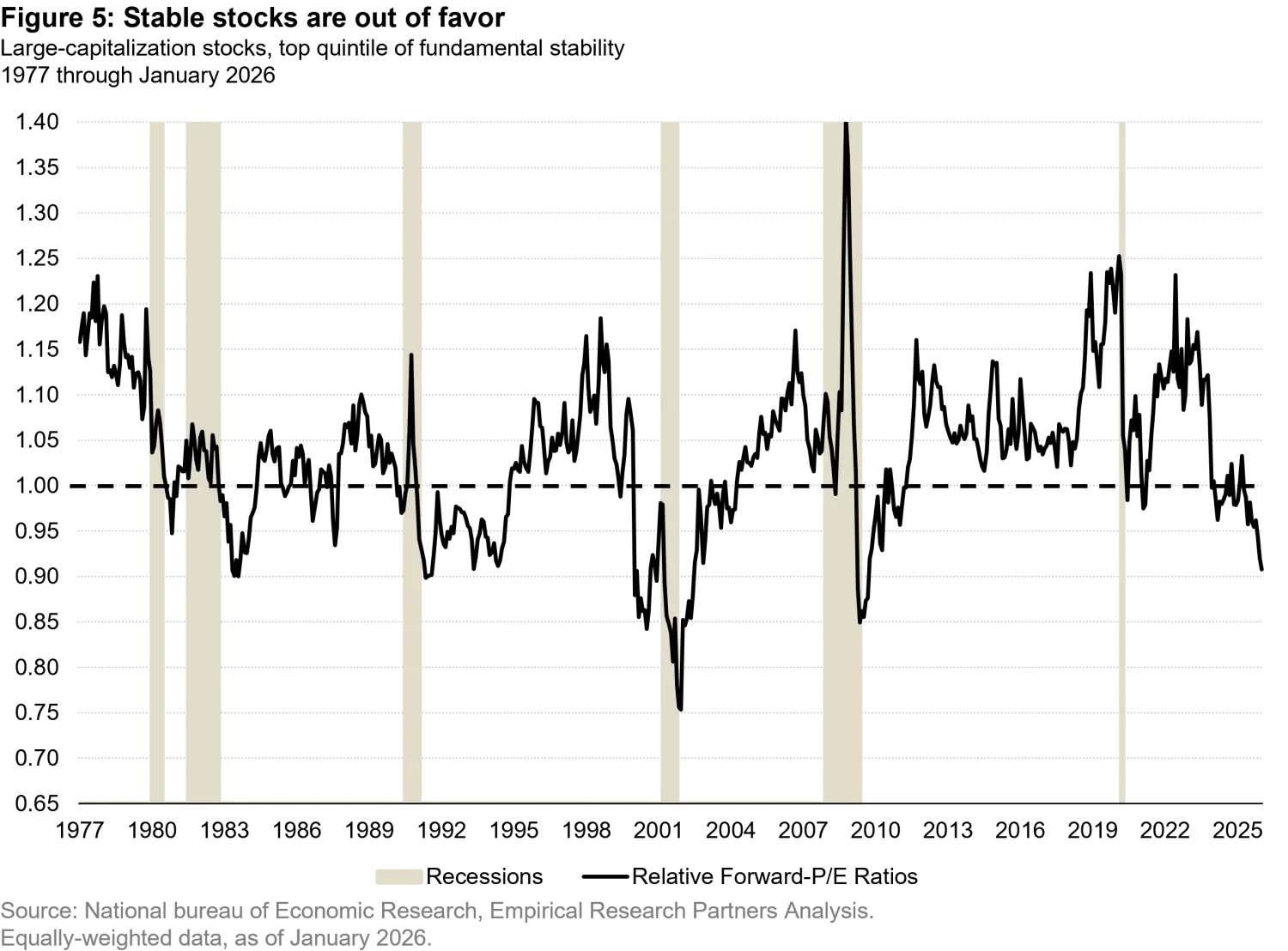

And yet, investors are sleeping like babies. Risk management has become an afterthought. Last year, quality stocks underperformed, while credit spreads between investment-grade corporate debt and Treasuries are tighter than skinny jeans (Figure 4).

Investing is ultimately an exercise in conviction – not only in what you choose to do, but also in what you consciously choose not to do. In this article, we reflect on several uncertainties surrounding AI that the market may be quietly sweeping under the rug and we share what we are choosing to do instead.

Will AI evolve in a continuous upward trend?

In a world filled with so many uncertainties, I turned to the most reliable opinion I could find: Large Language Models (LLMs). And even here, there is controversy. ChatGPT told me that “The bubble risk is in expectations and capital allocation, not in the technology.” Gemini, on the other hand, was more diplomatic, saying “Whether artificial intelligence (AI) is a bubble is a subject of intense debate among tech leaders, economists, and investors, with no consensus reached. The current market exhibits both classic bubble characteristics and fundamental differences from past booms, such as the dot-com era.”

There is no doubt that AI will be a transformative technology. The examples of its applications are real. Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, explains that up to 30% of Microsoft’s code is now being written by AI. Similarly, Dave Bozeman, CEO of C.H. Robinson, a US- based logistics company, argues that AI is transforming the company with direct impact to the bottom line, stating, “We (C.H Robinson) are an undervalued AI play.” McKinsey estimates that AI could contribute between 0.1% to 0.6% per year of labor productivity growth1.

History shows that the path to innovation is rarely linear

Vaclav Smil, a scientist specializing in energy transition, food production, and technical innovation, argues in his book Invention and Innovation: A Brief History of Hype and Failure that the path from invention to widespread application, i.e. innovation, usually takes longer than initially expected and frequently falls short of expectations.

Consider the example of electricity, clearly one of the most transformative technologies of the 20th century. While the first electric generators appeared in the late 19th century, meaningful productivity gains took 40 years to materialize. This was due to the time it took for factories to redesign their processes, which had been built around steam power. Similarly, we argue that today’s excitement around AI consumer-facing LLM’s will only translate into real productivity gains after private and public organizations successfully redesign their processes to harness the benefits of AI technology.

Periods of technological transition also bring about uncertainty around who the winners will be. In the early years of electricity, a fierce battle was fought between Alternating Current (AC) and Direct Current (DC) technologies. Despite Thomas Edison’s smear campaign to discredit AC technology, it ultimately became the global standard due to its cost advantage in transmitting electricity over long distances.

Similarly, during the personal computing era, PCs powered by Microsoft’s operating system went from zero market share in the mid-1970s to an overwhelming share of nearly 90% for almost 20 years. This dominance persisted until the PC began to lose relevance to smartphones in the 2010s.

As with the PC transition, Nokia and Blackberry, the initial leaders of the mobile phone era, became merely footnotes in the history of mobile computing after Apple and Samsung introduced smartphones. Ironically, Google, which started as a search platform operating on Microsoft’s Explorer browser during the PC era, became the dominant operating system in smartphones with the Android platform.

AI’s path may be similar to other technology transitions

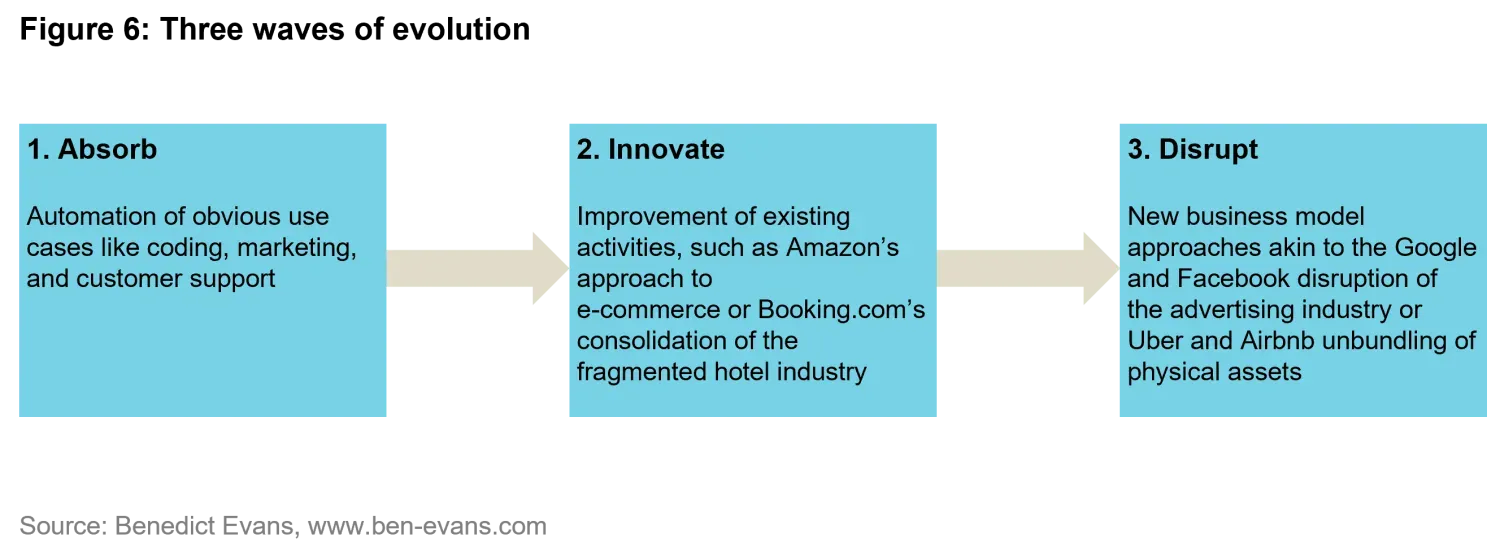

At the moment, the LLM market is quite open with dozens of models competing for dominance but little differentiation in performance among the leaders – Anthropic, Google and Open AI. Drawing from the evolution of past technological breakthroughs, Benedict Evans, a technology consultant and venture capitalist predicts that AI will follow the same three waves of evolution: absorb, innovate, disrupt (Figure 6).

Mr. Evans cautions that this transition will likely take longer than people expect. For example, after a decade, cloud computing accounts for only 30% of enterprise workloads. Similarly, e-commerce, despite its explosive growth over the last 30 years, has a share of just 15% of retail sales in the US.

What are the economics of AI?

Investors tend to compare the current AI cycle to the recent cycle of technological breakthroughs in software and the Internet. Both innovation cycles are similar in terms of digital innovation to enhance productivity and a “winner takes all” business model due to the economics of scale of leveraging the same LLM across a large customer base. However, AI differs in one important aspect: the capital intensity required to build large-scale datacenters and supply them with enormous amounts of power.

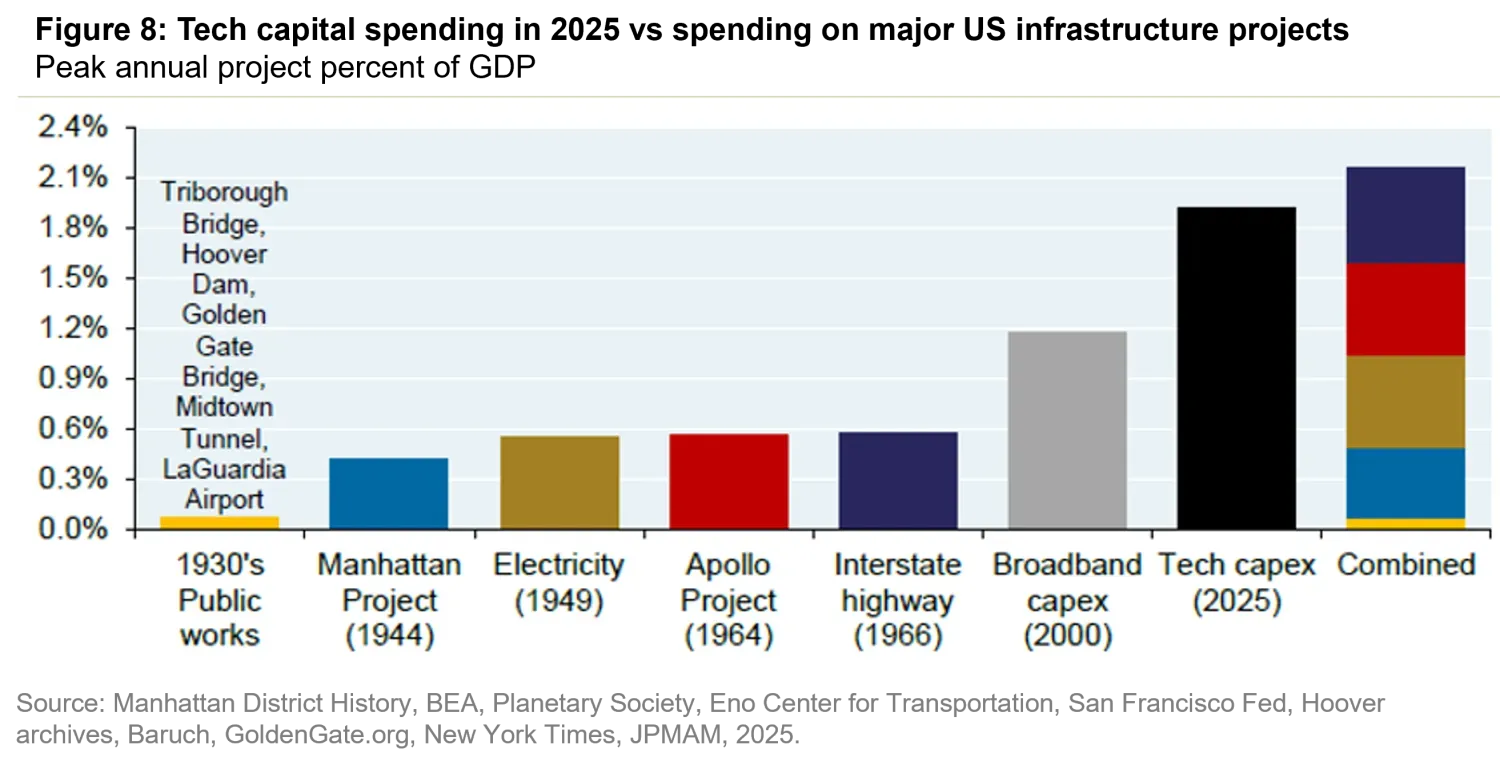

In a way, the AI industry is more akin to a hybrid of the software industry of the1980s and the major US infrastructure projects of the 20th century. Nevertheless, the magnitude of AI-related capital expenditures (capex) is astounding when viewed as a percentage of GDP, especially considering that AI projects often have shorter depreciation periods compared to traditional infrastructure investments.

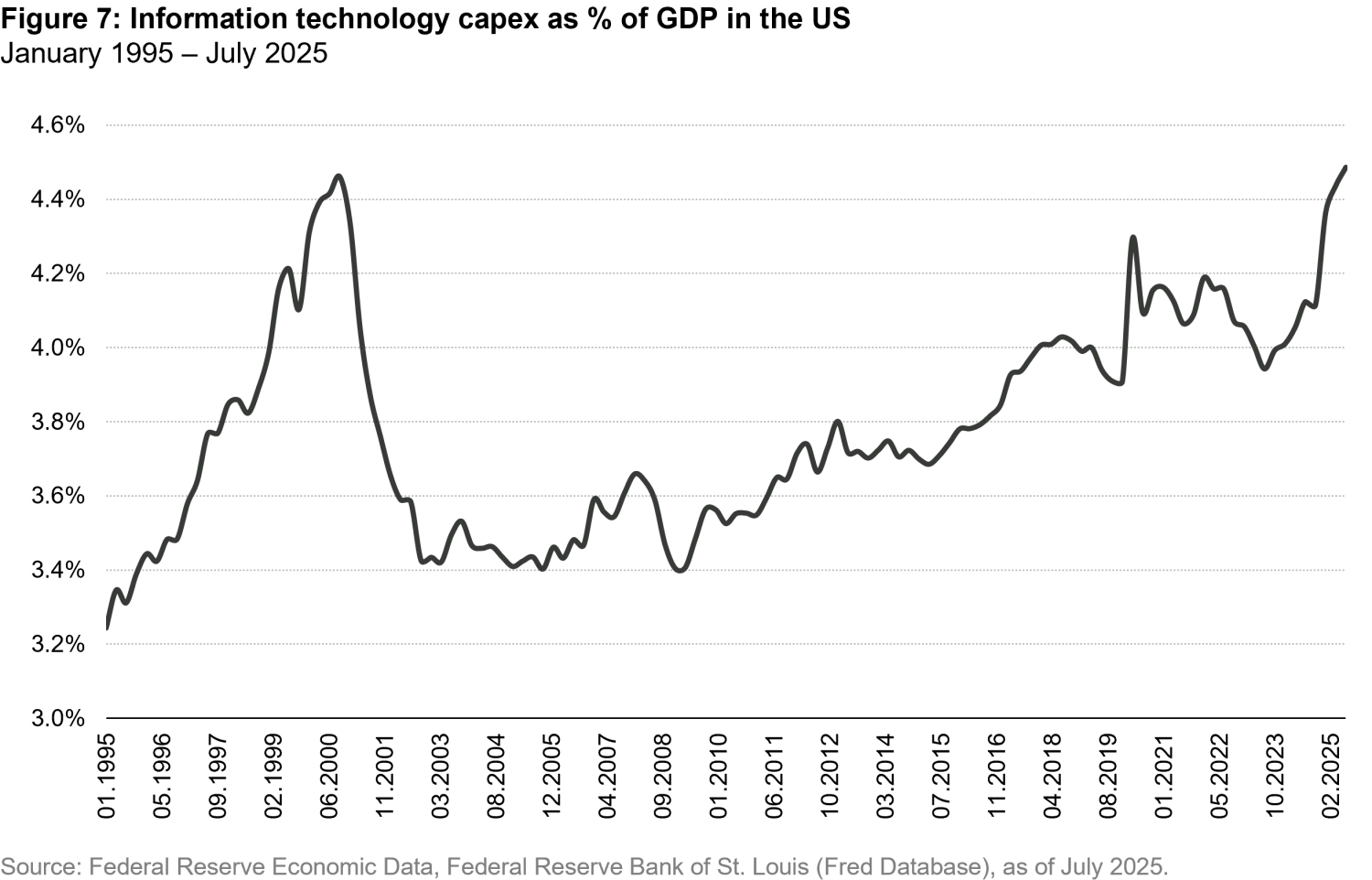

And the numbers just keep getting larger. In 2025, the “big four” AI hyperscalers, Meta, Microsoft, Google and Amazon, revised their investment in technology upward by 25% to USD 350 billion, a four-fold increase in the amount invested over the past five years. For 2026, their guidance for investments is on the order of USD 450 billion. These investments in technology are enormous even in historical terms. As a percentage of GDP, technology investment is now similar to levels observed in the dot-com era (Figure 7) and the total investment in technology in 2025 is equivalent to the combined investment of large US infrastructure projects over the last hundred years (Figure 8).

In an industry defined by “winner takes all” dynamics, where laggards are disrupted and consigned to oblivion, it is only natural for incumbents to suffer from “FOMO” (fear of missing out) anxiety while challengers adopt a “go for broke” strategy to secure their place at the top of the food chain. Open AI announced plans to invest close to USD 1.5 trillion in AI infrastructure over the next eight years while bleeding cash on a daily basis.

While the future of AI is uncertain, the laws of economics are immutable: for investments to be sustainable, they must eventually become self-financing and generate an adequate rate of return. The big four generate enough free cash flow to fund those massive AI investments, but large LLM developers rely on debt and equity financing, including circular financing agreements with their suppliers.

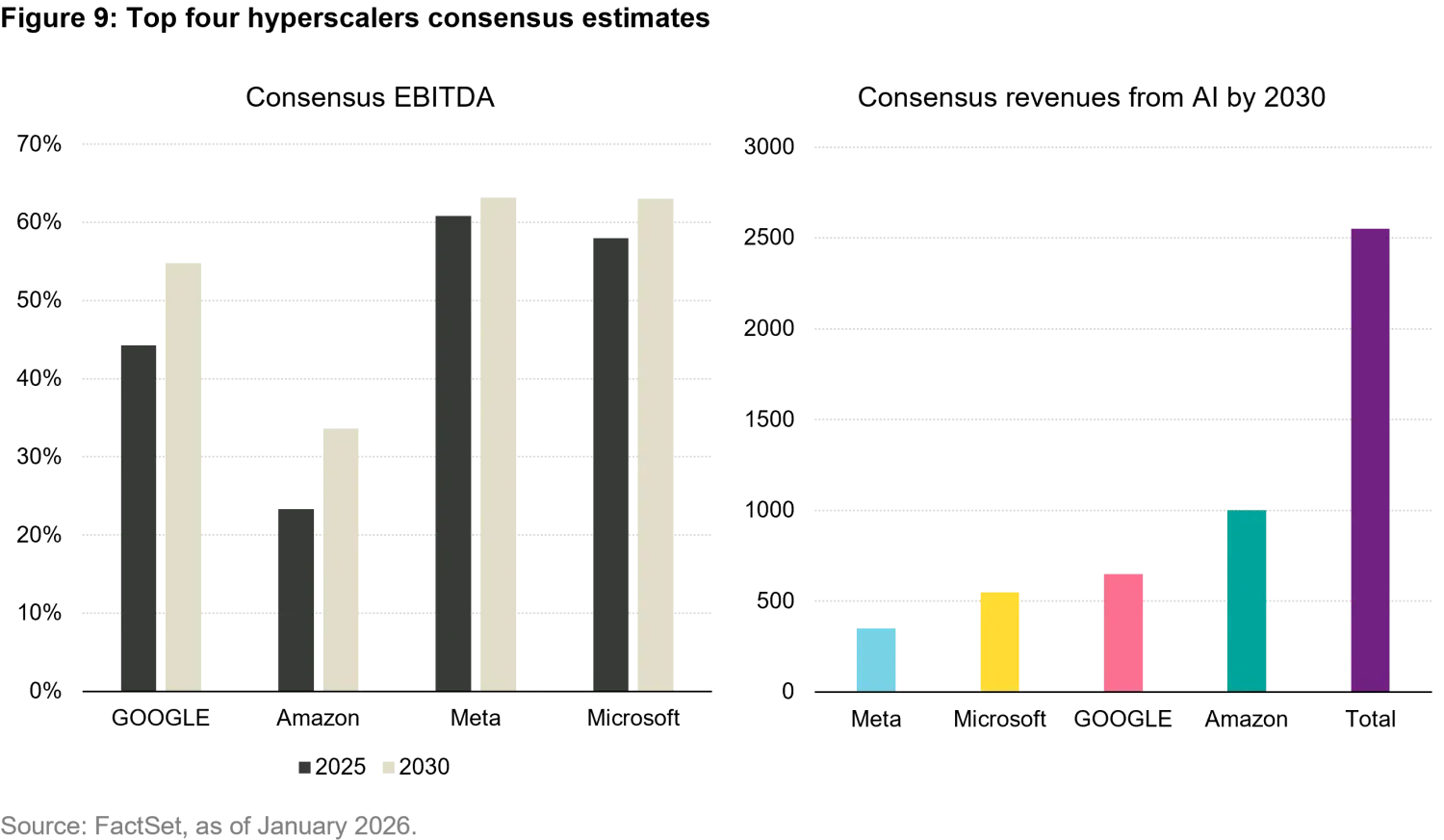

While uncertainties about the future business models and profitability of AI loom large, the equity market seems over-confident that all the pieces will fall into place. Based on consensus numbers, investments by AI hyperscalers should reach approximately USD 4 trillion over the next 5 years. Assuming a generous EBITDA margin of 60%, this would imply revenues of $2 trillion and EBITDA of $1.3 trillion by 2030. Interestingly, those projections are in line with consensus estimates (Figure 9).

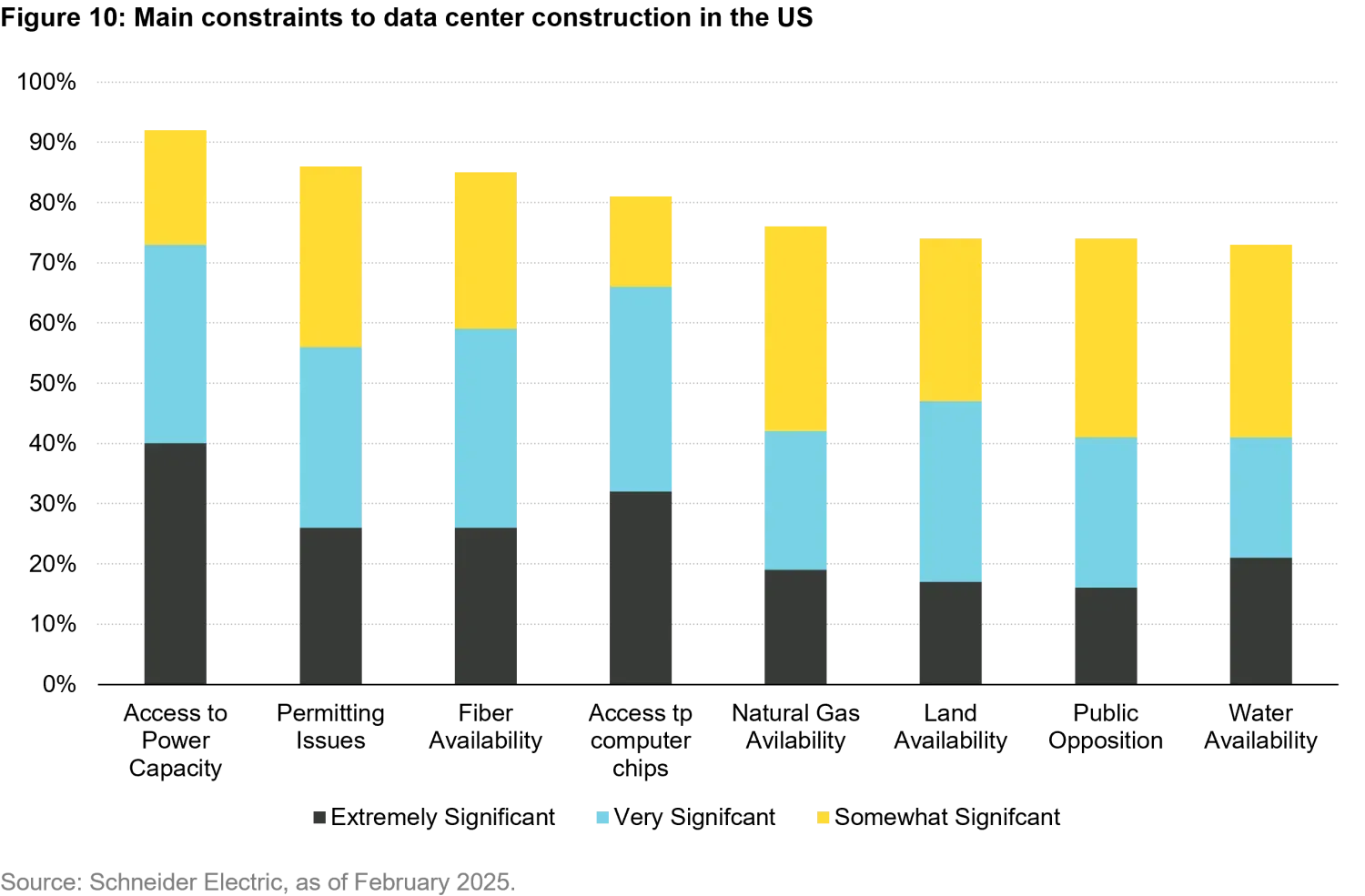

This tells us that sell side analysts are probably working with projections close to 80 GW (just for the four large hyperscalers) of additional power capacity being installed over the next 5 years to support AI growth. Experts project that the US will need to add between 100-200 GW of power capacity for AI datacenters over the next 5 years, or 20- 40 GW per year. To put this in perspective, the US adds, on average, 20-30 GW per year. This means AI could potentially account for one half to two-thirds of the incremental load.

The speed of development is already straining supply chains and creating price inflation. For example, there is a significant shortage of memory chips, with DRAM prices increasing by more than 100%. Manufacturers of power generation equipment indicate delivery times of 3-7 years for combined cycle turbines, with prices also rising by more than 100%. As a result, AI datacenter developers are turning to creative solutions, such as installing old aircraft engines or working with expensive diesel power generation. This trend has benefited companies like Caterpillar, which is known for its heavy construction machines. Caterpillar has seen exponential growth in its smaller power division, making it one of the best-performing stocks over the past 12 months.

Not surprisingly then, according to a survey of datacenter developers, 92% identified access to utility capacity and transmission networks as the major bottleneck for building more capacity (Figure 10).

Who will be disrupted?

One thing we know with certainty is that every technological transition creates both winners and losers. It is difficult to know at this point who the disruptors and the disrupted will be. Business models and applications are undefined, as mentioned above, and we are not sure where the technology will lead. The next “Google” of AI may very well be in the process of development in a garage anywhere in the world right now.

In his recent blog2, Professor Aswath Damodaran, Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University, provides an interesting analysis of the types of business models that are at risk of being disrupted by AI. He noted, “For businesses that are built around collecting and processing data, and charging high prices for that service, unless they can find other differentiators, they are exposed to disruption, with AI doing much of what they do.”

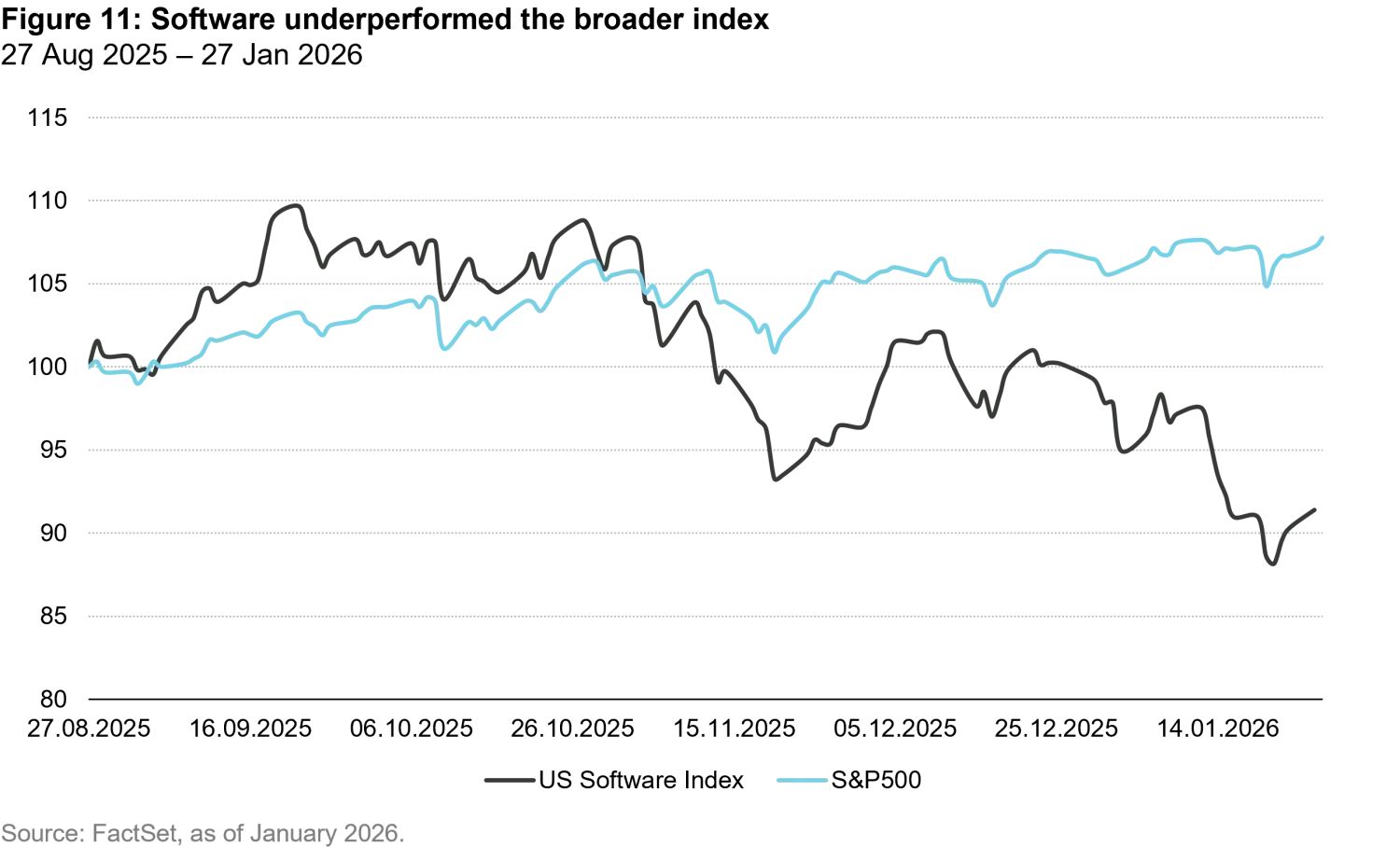

AI’s impact is already being felt in the software industry

Last year, software companies were among the worst performing stocks in the market. The market took the view that AI can write code better than humans, which will democratize access coding leading to an explosion in new software being introduced in the market, ultimately turning software into a commodity.

My colleague Max Rowland, our in-house futurist, developed an interesting framework to differentiate between those software companies with a moat and those at risk of being disrupted. Max believes that new development tools and autonomous agents are rapidly reducing software costs, lowering barriers to entry for new competitors.

However, incumbents remain protected by three key characteristics. First, network effects provide a powerful defense, as established user ecosystems are difficult to replicate. Second, platforms built on proprietary datasets are insulated from commoditization, as the primary value lies in the data rather than the code. Finally, complexity presents a moat against new entrants. While development costs have come down, human involvement is still needed, and it cannot be discounted that some complex pieces of software require rare specific domain knowledge. These characteristics are not mutually exclusive and, the more a company has, the wider its moat will be.

For example, RELX and Verisk both supply software to the insurance industry, which helps them price risk. This software is powered by claims data provided by the insurance companies. The software that these companies provide is not the value add and could be replicated easily. Their moat stems from their proprietary data, which would be difficult for a competitor to reproduce and market. HubSpot, a provider of CRM software, on the other hand, does not have proprietary data, network effects, or a complex product. In our view, HubSpot may have a tougher time defending against new competitors in the future.

Some things won’t change, and AI may make them even better

AI has the makings of an extraordinary technology and perhaps its impact will echo the great technological breakthroughs of the 20th century: electricity, the automobile, aviation and the personal computer.

It is too early to tell and, even so, history shows that investment returns do not always follow the hype of innovation. In fact, they tend to move in opposite directions, at least in the initial stages.

That said, despite the uncertainties regarding the future of AI, below are some examples where we are still finding long-term opportunities.

Travel: Travelling is a physical experience, at least until someone invents teleportation technology. Concerns that video call technology would replace business travel never materialized. Airplanes, however, need engines to fly and those engines are very expensive to develop and difficult to build. There are only three companies in the world that can make them at scale. These engines are built to last a long time and require a lot of maintenance, repairs, and spare parts to remain in operation. Two examples of aerospace companies are Safran and GE Aerospace.

Entertainment: If AI lives up to even half of the current hype, we will be able to accomplish far more in much less time. Hence, it begs the question, what are we going to do with all this free time? No worries, we have two groovy ideas for you – board and video games. There is nothing more retro and fun than playing board games with friends and family. One standout company in this space is Games Workshop, a UK-based midcap company with several popular gaming franchises, namely Warhammer 40k, based on futuristic war among armies of different galaxies. Players need to buy, build, and paint their figurines to build their armies, which can range from tens to hundreds of pieces. Games Workshop regularly introduces new figurines, keeping the game fresh and interesting and the players engaged

Video Games is a segment that some may argue is at risk of being replaced by AI since advancements in technology make it easier to develop new games. However, the best video games are often the result of the evolution of well-established franchises with a loyal following of fans. As long as developers continue to keep their games fresh and exciting, these franchises can likely thrive for long periods of time. For example, the charming plumbers Mario and Luigi have been entertaining generations of small and big kids for almost 50 years.

In the video game space, Capcom is a Japan-based company known for its iconic long-term franchises such as Resident Evil, Monster Hunter, and Street Fighter. We are also invested in Tencent, a Chinese company that owns and distributes popular games such as Honor Kings, League of Legends and Fortnite. Learn more in our recent article Beyond the AI bubble: finding predictable growth in video game stocks.

Luxury Goods: Since antiquity, when pharaohs and aristocrats used gold and rare pigments to signify divine connections and social standing, luxury items have acted as powerful status symbols that delineate class distinctions and communicate success. The world has changed a lot since the time of pharaohs. We may dress differently and have access to better technologies, but human desire for beauty and self-expression are essentially the same.

Not long ago, the only fashion available in China was the blue Mao suit. Today, China has become one of the largest markets for luxury goods, with all the major brands present on the high streets of its major cities. With or without AI, we believe that future generations of consumers will continue to be fascinated by the craftmanship and leather quality of a Hermès bag or the design, technology, and drivability of a Ferrari.

What we do know: stock prices invariably follow earnings growth

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that only a small number of portfolio managers active today were also managing money during the dot-com bubble of 1999/2000. I am proud to say that my colleague, Ed Walczack, a founding partner of the Vontobel Quality Growth Boutique, is one of them. Read Ed’s views in History often rhymes: the dot-com bubble vs today’s AI euphoria.

We believe investors should avoid what they do not know and invest in what they do know – companies with predictable earnings growth. As market history has shown, no matter the fad or the macro risk of the day, stock prices invariably follow earnings growth. In this way, we believe we can continue to help our clients protect capital and compound long-term wealth.

1. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/tech-and-ai/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier

2. Data update 1 for 2026: The Push and Pull of Data! https://aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com/2026/01/data-update-1-for-2026-push-and-pull-of.html