When the music stops: preparing your portfolio for the end of easy money

Quality Growth Boutique

Key takeaways

- The music has stopped in the capital markets, and speculative portfolios are unlikely to continue to outperform in the next cycle. If history is a guide, during market corrections in the last 50 years, on average, markets fell by 30% from peak to trough and it took 5 years to return to previous highs.

- In our view, a conservatively positioned portfolio of less-cyclical companies that have pricing power will be resilient. Investors should not confuse companies with exciting stories with those that are quality. Sometimes a great story turns out to be a Google, sometimes it’s a Yahoo.

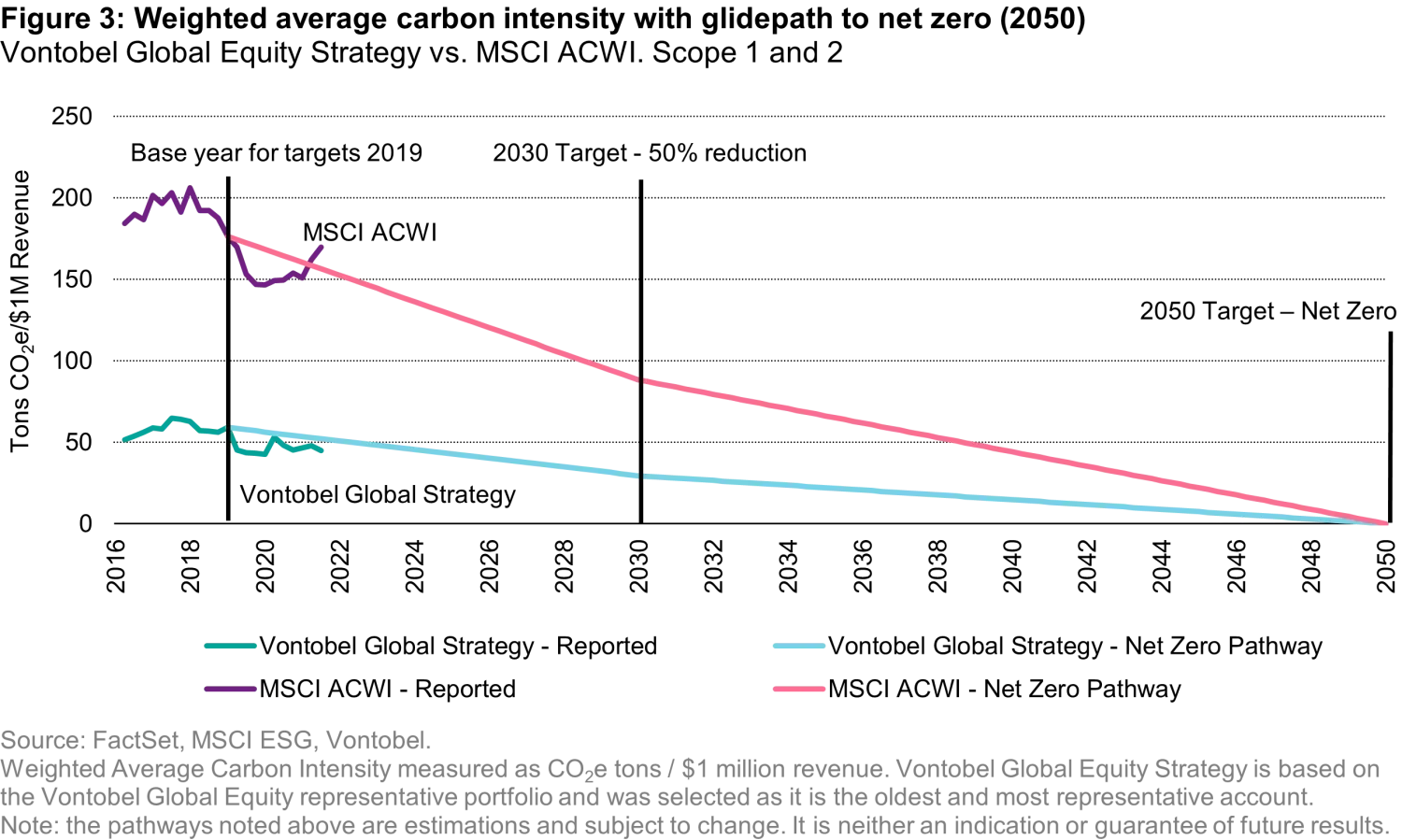

- Carbon emission liabilities are an underestimated risk to large CO2 emitter corporations. Most investors hesitate to adjust their fair value estimate to CO2 emission liabilities due to regulatory uncertainty, exposing them to the risk of material losses by ignoring environmental liabilities.

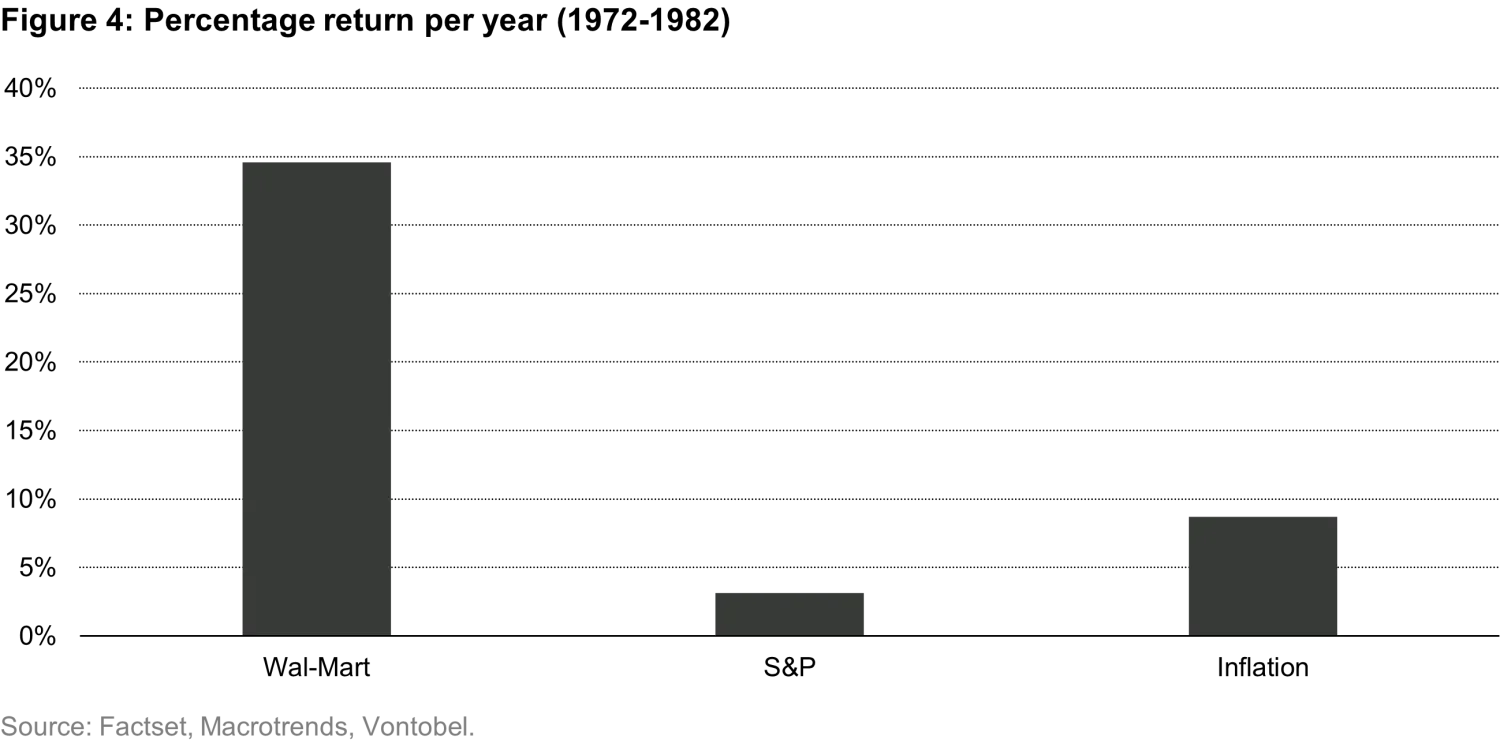

- Human ingenuity is not limited by the macro environment. Periods of great uncertainty can give way to prolific technological breakthroughs, and innovative companies can outperform despite inflation and economic volatility. In the 1970s, Wal-Mart handily outperformed both the market and inflation.

- The cycle of market excesses is coming to an end. We will continue to find great businesses and to seek to create absolute wealth for our clients even during difficult economic periods.

Chuck Prince, an ex-CEO of Citigroup, came to symbolize the excessive attitude towards risk on Wall Street that led to the global financial crisis after his infamous quote “…as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

The music has stopped in the capital markets. Ultra-low interest rates and TINA (There is No Alternative) are relics of the past. In our view, speculative portfolios that outperformed in the last five years are unlikely to do as well in the upcoming cycle.

I believe we are at the point of maximum uncertainty since the global financial crisis. Multiple forces are interacting simultaneously – persistently high inflation, war in Ukraine, high and volatile energy prices, and rising tension between the US and China. In complex systems, such as the weather and the global economy, small variations in input may result in large changes in long-term outcomes. Edward Lorenz, the founder of modern chaos theory, coined the term Butterfly Effect to explain this phenomenon – “A butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can produce a tornado in Texas.”

The recent panic in gilts is a case in point. The price of government bonds fell sharply, after the UK government announced a larger-than-expected package of energy subsidies and tax cuts. A decline in government bond prices was expected given the expansion of the fiscal deficit. Nevertheless, the price correction was exaggerated because of liability-driven investment strategies, a hedge designed to help pension funds manage expanding financial obligations due to a prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates. However, this had the unforeseen effect of triggering pension funds to sell gilts simultaneously to cover margin calls on derivatives ironically designed to protect portfolios.

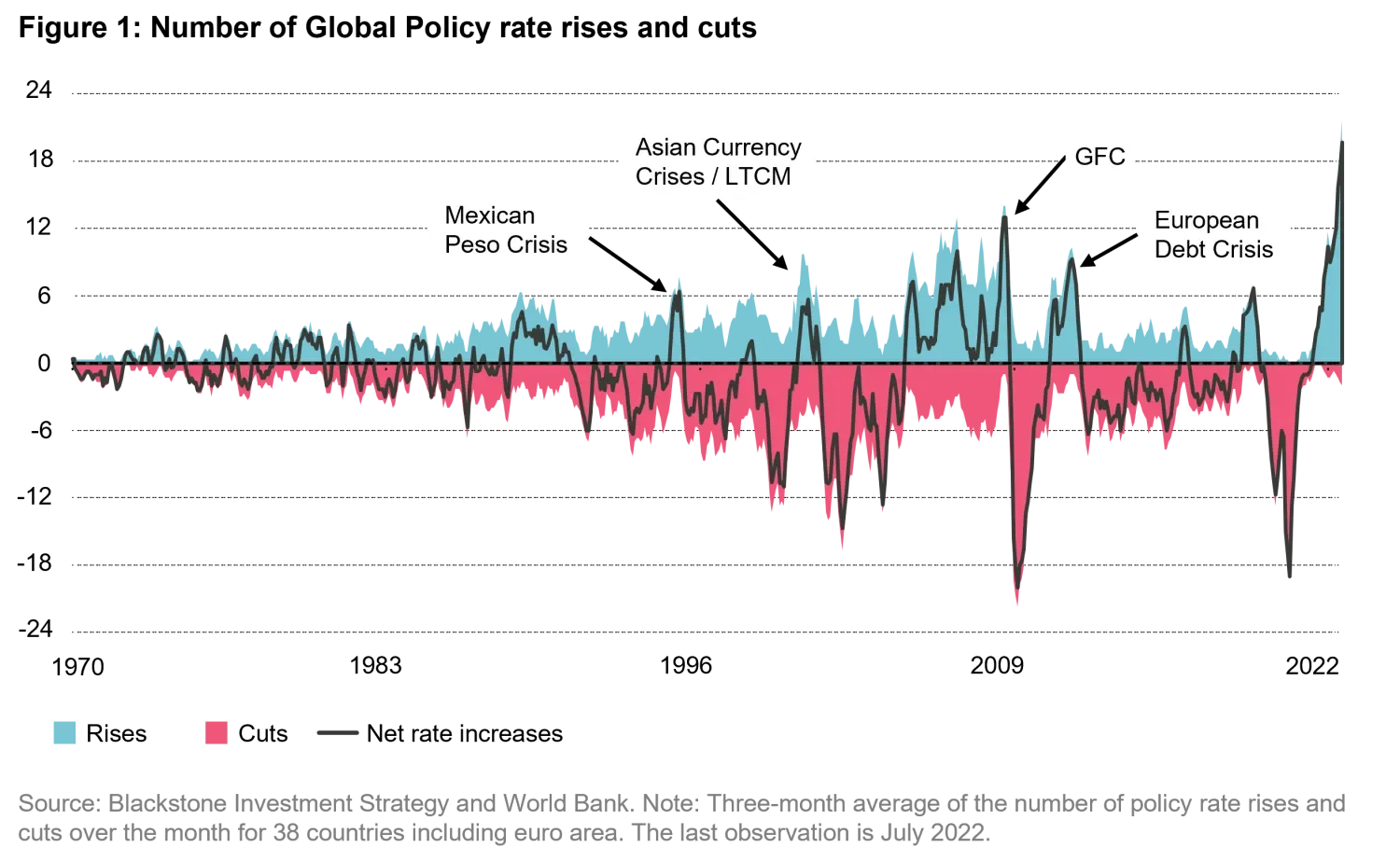

This is not the first time good intentions turned out to be disruptive to the financial markets. In the 1980s, “portfolio insurance”, a popular strategy adopted by institutional investors to limit market downside through automatic increases in short positions, helped fuel a one-day decline of 22.6%, the largest in the history of the stock market, also known as Black Monday. In JPMorgan Chase’s recent quarterly earnings call, Jamie Dimon, CEO, warned that investors should expect more blowups after the crash in UK government bonds. Economies around the globe have increased interest rates in a more coordinated fashion than ever before. History suggests that financial crises coincide with periods of large increases in global interest rates (Figure 1)

Preparation, downside protection, and profitability

While it is not always possible to accurately predict individual events, there are often advance warning signals which we can use to trigger preparations. Early in the year, we discussed the possibility of a market correction in our article Cloudy with a Chance of a Bear Market . While year to date, the S&P 500 is down by 20%, consensus numbers of 7% EPS growth in the next 12 months seem optimistic. In the last 30 years, the median earnings decline during recessions was in the low to mid-teens.

In the event of a market correction, downside protection can make a meaningful difference in the long-term accumulation of capital, since for a 50% loss of capital, investors will need to double their capital just to return to even. Looking back at market corrections over the last 50 years, on average, markets fell by 30% from peak to bottom and it took approximately 5 years to return to previous highs.

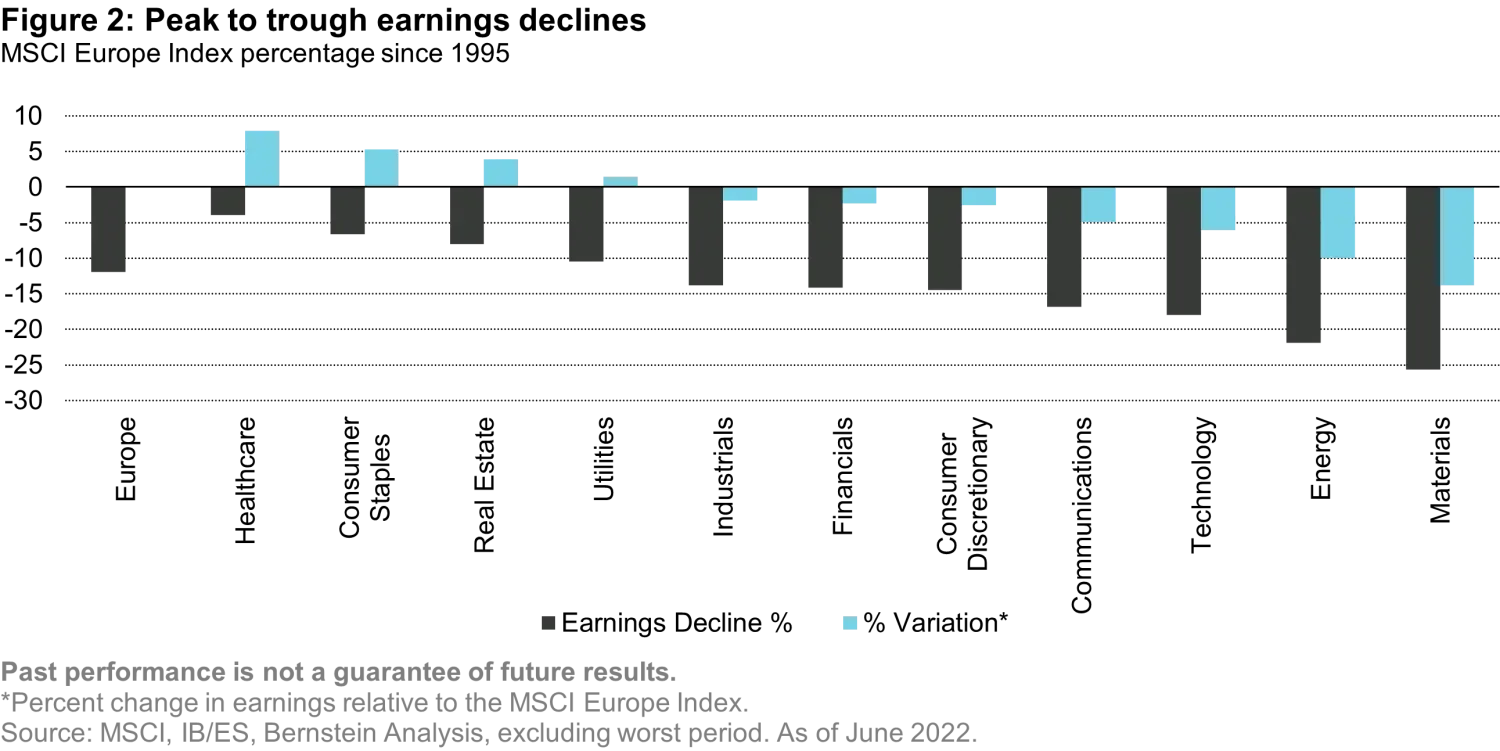

In a recession, not all companies are impacted equally. Companies that have pricing power in less-cyclical markets will fare better. In previous recessions, the difference in earnings declines between the best and worst sectors was material (Figure 2).

In the Vontobel International Equity strategy, we are conservatively positioned with an overweight to health care, consumer staples, and information technology, and an underweight to energy, materials, and financials. As a part of our risk mitigation process, each analyst on the team stress tests their names for earnings downside and balance-sheet risks for a recession scenario. In aggregate, we expect our portfolio companies to grow earnings in the low-single digits compared to a potential decline in aggregate earnings for the benchmark.

In our previous article,

Shades of Quality

, we argued that there’s a difference between quality companies and those with exciting stories. Shopify, for example, a Canadian e-commerce company, was one of the most popular stocks among international funds. But year to date, the stock is down more than 80%.

While Shopify has an interesting business model – a global platform to enable SME companies to sell online, and a huge total addressable market – the company is so far barely profitable. After many years of robust growth in gross merchandise volume (GMV), growth is coming in below expectations this year due to a shift in consumer spending to offline, a move from goods to services, and a weakening consumer spending environment. In July, management announced a 10% reduction in the workforce to adjust to this new reality.

Shopify may turn out to be a great opportunity. Nevertheless, in our definition of quality, a business needs to demonstrate a clear track record of profitable growth before being considered a viable investment. Until then, in our view, it is just an interesting story. Sometimes a great story turns out to be a Google, sometimes it’s a Yahoo.

Risk of ignoring carbon emission liabilities

At the moment, our concern is not limited to the risk of a recession. Carbon emission liabilities are one of the most material and under-rated risks to large CO2 emitter corporations such as heavy industrials and energy companies. Most investors hesitate to adjust their fair value estimate to CO2 emission liabilities due to regulatory uncertainty. Nevertheless, similar to the under-estimation of pension liabilities in the 90s and the exclusion of option-based compensation to earnings during the tech bubble, investors are at risk of material losses by ignoring environmental liabilities.

Take for example, Imperial Oil, one of Canada’s largest oil producers. Imperial Oil emits 23 million metric tons of CO2 per year with a carbon intensity of 1250 tons/revenues, almost 10x that of the majority of the companies in the benchmark. MSCI estimates that Imperial Oil’s climate value at risk is approximately $8 billion or 29% of its current market cap.

Imperial Oil has a long-term ambition to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. This will take massive investments in renewables, carbon capture and improvements in energy efficiency for a total investment in the billions of dollars. Imperial, like every other energy company, is a price taker and as such, investments in reduction of CO2 are not guaranteed to earn a return above the cost of capital. Unless one assumes that the price of oil will keep rising indefinitely in real terms at a time when oil demand is in structural decline. This is one of the reasons why energy companies are underweight in all our portfolios.

Due to the style of our International Equity strategy, we tend to concentrate on industries with low levels of CO2 emissions. Furthermore, Sudhir-Roc Sennet, our Head of Thought Leadership & ESG, developed a proprietary model ( How to Net Zero- seeking to achieve our goal and the goal ) that allows us to monitor the CO2 emissions for each company we own in the portfolio, and their long-term trajectory according to management guidance. We regularly monitor how most companies in the portfolio are doing relative to their targets, and to engage with management to ensure that they meet these targets. Figure 3 below illustrates the carbon intensity for our Global Equity portfolio, which is the broadest representative of our holdings across the Quality Growth Boutique.

Innovation ultimately creates value for shareholders

Despite the gloom and doom in the market these days, in the long-term, I am an optimist. Innovation ultimately creates value for shareholders and human ingenuity is not limited by the macro environment. In fact, periods of great uncertainty, like the first half of the 20th century, were prolific in technological breakthroughs such as the invention of the automobile, airplane, radio, and penicillin. Since the 1900s, life expectancy in the US has increased by 30 years from 48 to 78 years old (I am holding tight for every extra year). The world is not standing still; the number of patents issued in the United States doubled in the last decade.

It’s difficult to find great businesses that can perform through challenging markets, but not impossible. Wal-Mart is a perfect example: By revolutionizing supply-chain management in retail, Wal-Mart put forth a simple but powerful proposition – “Lowest Price Every Day”, turning a local chain of grocery stores in Arkansas into the largest global retailer with sales of US$600 billion. In the 1970s, despite high inflation and economic volatility, Wal-Mart’s stock price handily outperformed both the market and inflation.

The cycle of market excesses is coming to an end. While greed and fear will continue to drive markets, our investment philosophy anchors our foot on the ground during extreme ebullience or pessimism. Even during difficult economic periods, we will seek great businesses and aim to create absolute wealth for our clients.

Important Information: Companies discussed herein for illustrative purposes as means of illustrating our investment management and ESG processes. Presented for discussion purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any security. No assumption should be made as to the profitability or performance of any security associated with them. Further, the reader should not assume that any investments identified were or will be profitable or that any investment recommendations or that investment decisions we make in the future will be profitable.

Certain information herein based upon forward-looking statements, information and opinions, including descriptions of anticipated market changes and expectations of future activity. We believe that such statements, information, and opinions are based upon reasonable estimates and assumptions. However, there is no assurance that estimates or assumptions regarding future financial performance of countries, markets and/or investments will prove accurate, and actual results may differ materially. Therefore, undue reliance should not be placed on such forward-looking statements, information and opinions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current or future performance.

Environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) investing and criteria employed may be subjective in nature. The considerations assessed as part of ESG processes may vary across types of investments and issuers and not every factor may be identified or considered for all investments. Information used to evaluate ESG components may vary across providers and issuers as ESG is not a uniformly defined characteristic. ESG investing may forego market opportunities available to strategies which do not utilize such criteria. There is no guarantee the criteria and techniques employed will be successful.