An introduction to global CLOs

TwentyFour

Collateralised loan obligations, or CLOs, have become an increasingly popular asset class within global fixed income. While CLOs share a number of features with other securitisations such as mortgage-backed securities, the key distinction is that CLOs are backed almost exclusively by leveraged loans and the portfolio is actively managed.

Today, the global broadly-syndicated CLO market stands at around $1.2tr, with US CLOs accounting for the majority at $930bn (this excludes around $131bn of smaller “middle market” US CLOs) and the European market making up the remaining $290bn having grown rapidly in recent years. 1

Since their introduction in the late 1990s, we have seen CLOs grow into a mature asset class that has exhibited strong performance across multiple market cycles. With typically higher yields than similarly rated credit assets and a historically low default rate, we believe CLOs consistently offer one of the most attractive risk-return profiles in global fixed income.

What can CLOs offer investors?

Investors who include CLOs in their fixed income portfolio can benefit from several distinct characteristics of the asset class.

What is a CLO?

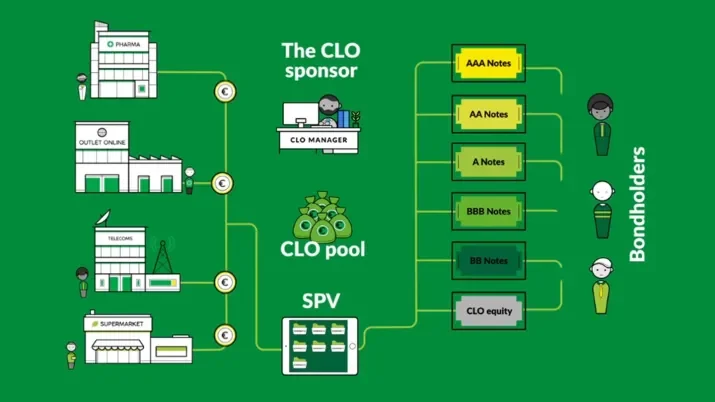

Like other forms of securitisation, a CLO funds the purchase of a portfolio of assets by selling securities to investors at varying levels of credit risk.

For CLOs, the portfolio of assets is almost exclusively made up of leveraged loans, which are senior secured corporate loans made by banks to typically non-IG companies (those rated BB+ or lower).

The layers of securities sold to investors, known as tranches, generally carry different ratings and offer different yields depending on their seniority in the structure (see Exhibit 1). A typical CLO comprises five or six tranches of bonds rated between AAA and B, plus one tranche of unrated equity.

As the leveraged loans in the CLO pool pay interest and principal, this pays interest and principal on the bonds in order of seniority.

The AAA tranche at the top is the first in line for payment, while the equity tranche at the bottom is the first to suffer any credit losses, which – on the rare occasion they occur – flow up the layers in the same way as payments feed down.

Unlike the bond tranches, the equity tranche does not have a set coupon; the equity tranche represents a claim on all excess cashflows once the obligations for each debt tranche have been met.

What is a leveraged loan?

Leveraged loans are senior secured corporate loans made by banks to typically non-IG companies (those rated BB+ or lower). Leveraged loans can be thought of as the “raw material” in CLOs; it is the cashflows from the repayments on these loans that pay the coupons of the CLO’s bondholders.

Senior secured loans enjoy the highest claim on a company’s assets in the event of a bankruptcy. Therefore, they are considered the least risky investment in non-IG corporates.

A typical loan included in a CLO portfolio generally has a rating between BB+ and B-, a maturity of around five to seven years, and floating rate interest payments indexed to either the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) or Euribor.

As of May 2025, outstanding leveraged loans totalled $1.5tr in the US and €344bn in Europe. 2 Leveraged loans are an investable asset class in themselves with an active secondary market, which enables CLO managers to build a portfolio of loans that is well diversified by industry and geography.

How big is the global CLO market?

The global CLO market currently stands at around $1.2tr.

As Exhibit 2 shows, the volume of CLOs outstanding plateaued in the wake of the global financial crisis as demand for securitised investments faded. A new era, dubbed CLO 2.0, began in 2010 in the US with deals that were structured to reduce risk for bondholders. Compared to pre-crisis deals (which became known as CLO 1.0), this new vintage of CLOs generally feature lower leverage, greater subordination and more stringent rating and collateral tests. Newer deals also shorten the period during which a CLO manager is able to actively manage the portfolio, which is aimed at limiting extension risk.

Europe’s CLO 2.0 era began in 2013, and primary market issuance has grown strongly in recent years to match increasing demand from investors – 2024 was a record year for post-crisis European CLO volume with €49bn of new deals in addition to €33bn of resets (see Exhibit 3).

The CLO investor base

CLO investor types tend to vary by tranche (see Exhibit 4). US, European and Japanese banks, for example, are very active buyers of AAA notes, with around 70% of the most senior notes from deals issued in 2024 being allocated to them according to CitiVelocity data.

Asset managers tend to be the biggest buyers of the lower rated mezzanine tranches. US insurance companies are a relevant player in these tranches as well, though their European peers are deterred by punitive capital treatment under Solvency II.

For CLO equity, the investor base has become more diverse in recent years. In 2024 we saw a significant increase in equity being allocated to third-party capital, including asset managers, hedge funds and private equity funds, marking a big shift from 2023 when the vast majority of equity positions were retained by CLO managers’ own captive equity funds.

In terms of geography, while we observe US investors generally make up 30-40% of the investor base for European CLOs, European investor participation in US deals is only around 20%, as a smaller proportion of US deals are considered compliant with EU risk retention rules.

Trading and liquidity in CLOs

One distinct feature of CLOs is the way they are traded, with around 25% of all secondary market trading occurring via Bids Wanted in Competition (BWIC) lists.

In more mainstream markets such as government and corporate bonds, dealers “make markets” by matching buyers and sellers directly and holding an inventory of securities on their own book for providing liquidity to clients.

For CLOs, BWICs are an additional source of client-to-client liquidity, which can help to mitigate liquidity risk. Investors can share a list of their bonds available for sale with dealers, who then share the list with their clients. The bonds are effectively sold via an auction process, which allows investors to receive bids from the broader market, which can help them to achieve better execution. Colour on BWIC execution is also generally shared with the market after trading, which helps contributes to better market transparency and overall liquidity, another marked difference from mainstream bonds where colour on trading flows is often a closely guarded commodity for dealers. Dealers that have executed a BWIC trade often share the second best bid price they received, for example, which can be particularly useful for holders of less liquid mezzanine CLO bonds as bid levels give an indication of where these bonds could be traded.

As Exhibit 5 shows, BWIC activity has grown in recent years with annual trading volume more than doubling between 2017 and 2024. Notably, BWIC volume has tended to increase in periods of greater volatility (such as early 2020 and late 2022) which can give CLO investors access to an additional source of liquidity when they may need it most. This differs slightly to secondary trading in more mainstream bond markets, where dealers’ appetite for making markets tends to decrease in volatile periods as there is an increased risk to holding bonds on their balance sheets.

How are CLOs managed?

CLOs are actively managed by an asset manager. The CLO manager typically selects a large number of loans (120-350) from companies of different sizes, geographies and industries to build as diverse a portfolio of corporate loans as possible – this helps to mitigate the default and recovery risk presented by the individual companies in the portfolio. The CLO manager can acquire or dispose of loans in an effort to optimise returns, but they are subject to strict limitations regarding the type, quality and underlying features of the assets.

These loans are placed into a special purpose vehicle (SPV) which houses the assets so they can be administered by the CLO manager. The purpose of the SPV is to hold the assets and distribute interest and principal to bondholders. This also means that CLOs, like other types of asset-backed securities, are “bankruptcy remote”; bondholders’ credit risk is contained to the underlying assets rather than the issuer of the CLO.

Additionally, the SPV provides investors in the CLO with transparency; they can see the exact details of every company in the portfolio, from its credit rating and management to the specific terms of the loan.

As a result, CLO bondholders can continually analyse the companies to which they are exposed and assess the performance of the CLO manager, which can help to further mitigate the default and recovery risk of the underlying assets. Investors can also stress test the portfolio and run adverse scenarios, in order to understand what might happen to the CLO’s returns under changing economic and market conditions which might negatively impact asset performance.

The lifecycle of a CLO

There are several specific phases in the lifecycle of a typical CLO (see Exhibit 6).

The first is known as the warehouse period, which typically lasts several months. During the warehouse period the CLO manager will acquire the leveraged loans needed to construct the portfolio, delving into the market where the manager sees opportunity.

The next phase is the ramp-up period. The ramp-up period lasts a further six months and the manager will use this time to make further purchases. Once the manager finishes acquiring new assets, the CLO will become live and the CLO manager will shift their attention from building the portfolio to its management.

The CLO then enters its reinvestment period. At this stage, the CLO manager is permitted to actively trade the portfolio and reinvestment using principal cash flows. The reinvestment period can last up to five years and the manager’s goal is to maximise the performance of the portfolio.

A CLO’s non-call period begins at the same time as the reinvestment period. During this phase, typically lasting six months to two years, the manager cannot refinance any outstanding CLO notes. Afterwards, the majority of equity noteholders have the right to refinance any outstanding notes.

Finally, the CLO enters its amortisation period, if it is not refinanced prior to this. The CLO manager is no longer able to reinvest any principal cashflows, and the cashflows are used to pay down the outstanding CLO notes. At the end of the amortisation period, a CLO is considered successful (in common with all fixed income investments) if its investors have been repaid their principal investment along with the promised interest payments.

Analysing a CLO

While CLOs are becoming increasingly mainstream and appearing in more investor portfolios, they are still considered a specialist credit product, and one that in our view demands a certain level of expertise and resources dedicated to performing due diligence on the assets in order to understand and mitigate risks.

When analysing individual CLOs, we concentrate on three fundamental components:

1. The manager

There are material differences between CLO managers which can impact the relative attractiveness of their transactions.

Different managers can manage CLOs in very different ways, and this mostly reflects the firm’s risk-taking culture and the incentives attached to equity returns. For example, CLOs where the majority of the equity is provided by third-party capital tend to have more aggressive target returns than deals where the manager uses its own funds. CLO managers are compensated through management fees (typically 0.4-0.5%), and through whatever portion of the equity tranche they retain, which provides additional financial income.

One key parameter we look at is a manager’s trading style, for example how quickly they look to have identified and exited problem assets. More formal due diligence can be performed on a CLO manager’s risk management and compliance capabilities, its investment process and other systems. However, factors such as staff turnover and corporate culture can be equally important.

There are over 150 active CLO managers in the US, and around half that in Europe. Increasingly, the larger managers with strong track records operate and issue CLOs in both markets (see Exhibit 7).

2. The pool

CLO investors have complete transparency on the asset pool, which means there is a huge amount of data available for analysing the underlying loans. Having access to the assets in a CLO pool allows investors to scrutinise the broader characteristics of the pool when the CLO is issued, and also monitor metrics such as concentration risks at the pool level over time – this work forms the basis for cashflow modelling.

Because the CLO manager typically has the ability to buy and sell loans for the first five years of the CLO’s life, an investor’s assumptions around the reinvestment profile are also important. To determine what they expect a CLO portfolio to look like over the years, and thus better project future cashflows or potential risks, investors also need to have an understanding of the dynamics of the leveraged loan market, such as:

- Issuance

- Spread performance

- Broad market default cycle

- Prepayments and refinancing

Internally, modelling and stress-testing with adverse economic scenarios can also be performed on the pool to understand the level of underperformance the model suggests would be required to impact returns on the different tranches (this is usually substantial given the credit protection afforded by the CLO structure).

3. The structure – built-in protections for investors

While CLO structures and documentation are somewhat standardised, every CLO is different, so investors must individually analyse the specific features of each CLO and constantly monitor the characteristics and performance of the loan portfolio.

Like with other fixed income securities, CLO bondholders are subject to credit, liquidity and mark-to-market risks. However, when it comes to credit risk, CLO investors benefit from a number of features which are intended to protect their coupon and principal payments from potential losses on the underlying assets.

The major structural protections for investors are:

Subordination

Subordination is created by the structure of the CLO itself, with each lower rated tranche providing subordination to all the tranches above. The level of subordination enjoyed by each tranche will vary from deal to deal depending on their relative sizes. For bondholders, the most important source of subordination is the equity tranche, which is seen as the most risky and normally highest yielding as it is the first to absorb any losses from the collateral pool.

Credit enhancement

Credit enhancement refers to techniques used by CLO managers to improve the creditworthiness of the debt tranches of CLOs. These include features such as overcollateralisation (ensuring the principal value of the underlying loans exceeds that of the CLO’s debt) and cash reserve funds, whereby a predetermined proportion of cashflows is held back to make up any shortfall in coupon payments that might occur as a result of unexpected portfolio losses.

Portfolio limits and collateral tests

To further increase the comfort of investors and mitigate risks, CLO managers make binding commitments on how they will build and manage the asset pool. Limits are set on exposure to lower rated loans or exposure to certain industries, for example, to address concentration risk. CLO managers also implement collateral quality tests, which establish minimum levels for metrics such as overcollateralisation and interest coverage ratios. If these measures dip below their minimum thresholds, then cashflows can be diverted away from the equity and junior tranches to either repay the principal value of the senior tranches or to purchase additional assets to restore the portfolio to the minimum thresholds.

US vs. European CLOs

While US and European CLOs are structurally usually very similar, there are important differences in the risk-return profiles of the two markets.

The most obvious one is size. The US market is four times larger at around $930bn, though the European market has grown steadily in recent years and is expected to keep doing so, with new CLO managers entering the space and US CLO managers increasingly looking to issue deals in Europe.

In terms of the CLOs themselves, one key difference is risk retention. In Europe, regulation requires CLO managers to retain a minimum 5% economic stake in every CLO they issue to ensure alignment of interest with investors. Issuers typically achieve this by taking a “vertical slice” of the deal, retaining 5% of each tranche. US CLOs have effectively been exempt from risk retention rules since 2018, though some issuers voluntarily meet the requirement in order to increase the comfort of bondholders.

In terms of collateral, European CLO pools tend to have larger B2/B rated exposures than their US counterparts, though US pools tend to have more CCC rated exposures. US CLOs tend to be more diversified by industry, but US managers tend to deploy more leverage in their deal structures. European CLOs clearly offer greater geographical diversification given they are generally pan-European, though the assets tend to be heavily weighted towards Western European economies.

Sector exposures in US and European CLOs have shifted over time, but as Exhibit 8 shows, there are meaningful differences in certain sectors which reflect the make-up of the US and European economies.

European CLO investors tend to benefit from greater structural protection, and leveraged loan documentation in the US tends to be weaker.

On the whole, European CLOs have performed better during historical periods of weakness; they experienced lower losses through the global financial crisis, for example, and fewer downgrades during the Covid-19 crisis.

Historical performance: CLOs have a strong default record

As a result of the structural protections described above, CLO debt tranches have historically delivered much stronger credit performance than direct investments in leveraged loans.

Even during the global financial crisis, when leveraged loan default rates peaked above 10%, the vast majority of CLOs were able to pay coupons and principal to investors. This is partly due to the active management of CLO portfolios, which enables CLO managers to pick up additional assets at depressed valuations during periods of market stress. Of the 5,797 pre-crisis CLO tranches rated by S&P globally, just 62 experienced a default (either a missed interest payment or a principal loss), giving a lifetime default rate of 1.07%.3

The historical credit performance of CLO debt also compares favourably to similarly rated corporate debt. Since peaking at 2.53% in 2002, the annual default rate for sub-IG CLO tranches (those rated BB+ or lower) has never exceeded 1%, compared to a long-term average default rate of around 4% for sub-IG corporate bonds (see Exhibit 9). No AAA rated CLO tranche has ever defaulted, according to S&P data, while for European CLOs there have been zero defaults in sub-IG CLOs issued post-2008.

On top of this strong historical performance, it is worth noting how big a buffer against portfolio losses CLO debt tranches have thanks to features such as subordination and credit enhancement. With complete transparency on the composition of the loan portfolio and the structure of the CLO, bondholders can calculate a “breakeven” level for each tranche – i.e. a threshold level of cumulative defaults the asset pool would have to experience to trigger the first dollar of principal loss.

Using an illustrative example of a typical European CLO, Exhibit 10 shows how the default thresholds for both AAA and BBB CLOs provide a large buffer against the rolling default rate on CLO collateral.

How do CLO spreads compare to corporate debt?

As Exhibit 11 shows, CLOs have tended to offer a material spread premium over corporate bond markets of a similar rating.

This is partly down to the perceived complexity of the asset class and its more comprehensive underwriting process. However, another factor in our view is that CLOs, despite their growing popularity, remain an under-researched and poorly understood asset class across the wider investment community, which helps to preserve the spread premium over more mainstream fixed income markets despite their comparatively attractive risk profile.

How do CLO returns compare to corporate debt?

This excess spread means that CLOs have historically tended to deliver excess return versus corporate debt of a similar rating (see Exhibit 12).

Over the past five years, the annualised return of both US and European BB rated CLOs has far outstripped that of their respective HY bond indices, whose average ratings are also BB. The same is true for BBB CLOs against their respective IG corporate bond indices. It is also worth noting the material outperformance of AAA CLOs against IG credit given their far superior credit quality.

Conclusion

We have consistently viewed the risk-return profile of CLOs as one of the most attractive available in global fixed income.

Higher yields than similarly rated corporate debt, historically strong credit performance and built-in protections for investors are all attractive features of the market in our view, and the flexibility of the structures means they can be suitable for investors of varying risk appetites.

However, CLOs are a specialist asset class and they are undoubtedly more complex than more mainstream areas of fixed income such as high yield bonds. In our view, understanding the risks and aiming to maximise returns in this market requires specialist knowledge and dedicated resources for analysing managers, deal structures and collateral pools effectively.

1 BAML Factbook, 20 December 2024

2 JP Morgan Leveraged Loan Index, 30 May 2025

3 S&P Global Ratings, 31 December 2023

Important Information

The views expressed represent the opinions of TwentyFour as at 30 June 2025, they may change, and may also not be shared by other members of the Vontobel Group. The analysis is based on publicly available information as of the date above and is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or a personal recommendation.

Any projections, forecasts or estimates contained herein are based on a variety of estimates and assumptions. Market expectations and forward-looking statements are opinion, they are not guaranteed and are subject to change. There can be no assurance that estimates or assumptions regarding future financial performance of countries, markets and/or investments will prove accurate, and actual results may differ materially. The inclusion of projections or forecasts should not be regarded as an indication that TwentyFour or Vontobel considers the projections or forecasts to be reliable predictors of future events, and they should not be relied upon as such. We reserve the right to make changes and corrections to the information and opinions expressed herein at any time, without notice.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Value and income received are not guaranteed and one may get back less than originally invested. Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against loss. TwentyFour, its affiliates and the individuals associated therewith may (in various capacities) have positions or deal in securities (or related derivatives) identical or similar to those described herein.

Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. In particular investors in collateralised loan obligations (CLOs), and other forms of asset-backed securities, generally receive payments that are part interest and part return of principal. These payments may vary based on the rate at which the underlying borrowers pay off their loans. These instruments are particularly subject to credit and liquidity and valuation risks. High-yield bonds may present additional risks because these securities may be less liquid, and therefore more difficult to value accurately and sell at an advantageous price or time, and present more credit risk than investment-grade bonds.

CLOs are themselves subject to credit, liquidity, and mark-to-market risk, and the basic architecture of CLOs requires that investors must understand the waterfall mechanisms and protections as well as the terms, conditions, and credit profile of the underlying loan collateral. CLOs are therefore considered complex investments and not suitable for all investors. The loans that underlie the CLO involve special types of risks, including credit risk, interest rate risk, counterparty risk, and prepayment risk. These underlying loans may offer a fixed or floating interest rate and are often generally below investment grade, may be unrated, and can be difficult to value accurately and may be more susceptible to liquidity risk than fixed-income instruments of similar credit quality and/or maturity.