Energy, metal, and grain prices spike after Putin’s aggression

Quantitative Investments

Key takeaways

- After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, western importers of Russian energy, grains, and metals are wondering what’s in store for them

- Europe must prepare for another inflationary shock

- Nord Stream 2, the much-criticized gas pipeline between Germany and Russia, is now off the table.

- Russia sends two thirds of its oil exports westward and has never cut supplies except one time during World War II

- Russia, an eminent producer of palladium, aluminium, nickel, and platinum, supplies much of Germany’s auto industry.

- Ukraine and Russia account for almost a third of all global wheat exports

With Vladimir Putin’s designs on Ukraine now becoming apparent, western importers of Russian energy, grains, and metals are wondering what’s in store for them. To nobody’s surprise, commodity prices have risen to new record highs, contrasting the downturn on equity markets. Europe must prepare for another inflationary shock – and more human suffering.

Already in the run-up to the crisis, commodities were pricing in elevated geopolitical risks, and that has increased with Russia’s invasion as well as every daily escalation. The broad-based Bloomberg Commodity Index is up 26.5% year-to-date, while crude oil is up 50%, aluminium 30%, and wheat almost 45%.1 All commodity sectors are facing severe potential supply disruptions and are likely to create inflationary shocks in Europe the longer the war drags on. This isn’t the type of price increase people are prepared for. The combination of supply disruptions, rising prices, and low commodity inventories will ultimately have to lower demand. Central banks can’t do much because raising key rates would endanger the economic recovery, which makes inflation less transitory than thought at the start of the year.

Nord Stream 2 going south

Nord Stream 2, the much-criticized gas pipeline between Germany and Russia allowing Europe’s largest supplier to increase its already commanding market share, is now off the table. Germany, finally responding to calls from western allies, has stopped the approval process. This isn’t a problem in the short term as Europe has enough natural gas for the remaining weeks of winter weather. However, it’s now becoming clear there won’t be enough capacity to fill up Europe’s gas tanks later in the year. These are already 15% below their five-year average levels and may run almost dry before the next winter starts. Thus, natural gas prices are likely to remain high and volatile for the foreseeable future, causing electricity prices to stay elevated in Europe. The gravity of the problem was driven home by news that the German government may keep the remaining three nuclear power plants running, and even discuss extending the life of domestic coal mines. Similar policy changes are discussed in Eastern Europe and Italy but let’s not forget that some of these economies depend on Russian coal.

Russian oil deliveries are also in focus. The country, second only to Saudi Arabia in terms of global market share, sends two thirds of its oil exports westward, about 3.5 million barrels per day. So far, it has never cut Europe off, except one time during World War II, and wants to be seen as a reliable energy supplier even during crises. It’s also worth noting that the European Union's sanctions so far don’t extend to energy flows. But trouble is brewing for Russia as a producer (and Europe as a consumer) in a different area. A growing number of European, US, and even Chinese lenders are restricting financing for purchases of Russian commodities to reduce legal and reputational risk, and to mitigate the consequences of a Russian counterparty default. And of course, excluding Russian banks from the international payment system SWIFT makes money transfers cumbersome, stalling trade in physical commodities. Despite the current 20 USD discount Russia is offering on the barrel, no western consumer is willing, or indeed able, to trade. This means that inventories in Europe are in a rapid decline, falling daily by 2 to 3 million barrels.

Bring on more oil barrels

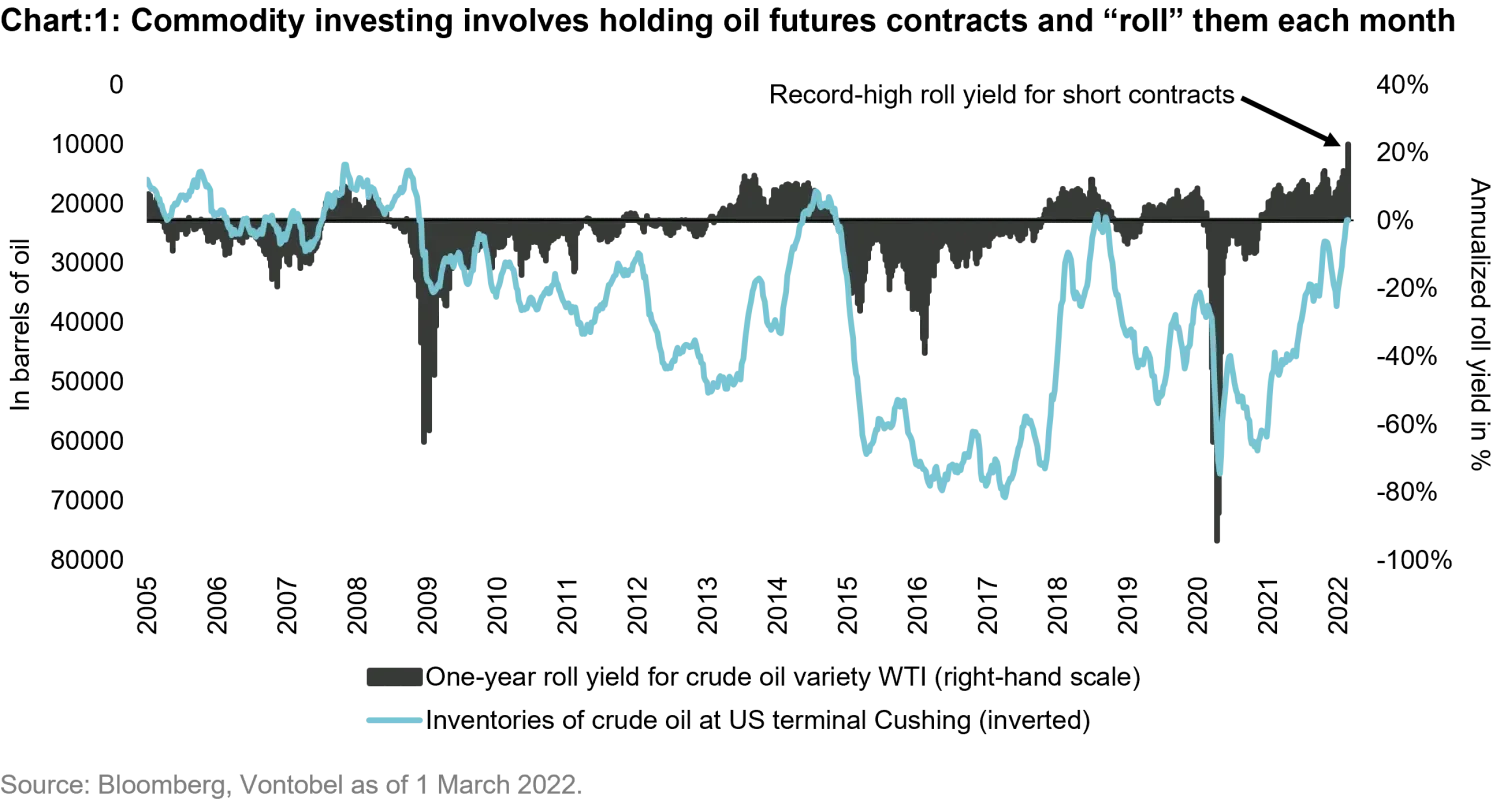

Russia is loosely tied to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which rarely lets geopolitical considerations guide its steps. As expected, the organization said in early March it would aim to raise production by 400,000 barrels a day in April, sticking to a pre-agreed path of modest monthly production increases. At the same time, western powers are trying to reach a deal with Iran to bring that country’s nuclear energy program under control. If these negotiations succeed, Iran would be allowed to sell its oil globally again, and markets are increasingly expecting such an agreement. But even a come-back of Iran as an exporter would only result in a daily addition of 1 million barrels per day at the most within three to six months, too little to make up for a possible loss of Russian oil deliveries. To put this into perspective: the announcement of the US government to release another 60 million barrels of strategic oil reserves failed to calm energy markets. With oil inventories in a continued decline, so-called roll returns have spiked to record highs for crude oil, meaning that buyers are paying a significant premium to secure instant delivery of the commodity. Rolling futures contracts – selling contracts that are about to expire, buying longer-running ones instead – is a commodity futures trader’s daily bread, and the gain on such transactions is called the risk premium. Given that oil inventories can only go down, futures contracts with short maturities could easily spike to USD 150 per barrel, we reckon, increasing the risk premium further (see chart 1).

Metals: pedal to the metal?

Less conspicuous, but of eminent importance nevertheless, is the effect of the war on metals. Russia, a metals heavyweight globally accounting for 40% of palladium, 6% of aluminium, 7% of nickel, and 10% of platinum production, supplies much of Germany’s auto industry. Carmakers would love to finally ramp up production after pandemic-linked disruptions, but metal deliveries from Russia seem highly uncertain now amid logistical and financing problems. Even shipping companies have started to refuse to transport metals coming from Russia. At the same time, European producers are hit by spiking natural gas prices and electricity costs because the smelting process is highly energy-intensive. Many European aluminium and zinc smelters have recently stopped working because they struggled to cover their costs. Given the currently high and volatile European natural gas prices (Dutch TTF natural gas +160% since the start of the year), the situation may not improve. All of this comes on top of already almost depleted metal inventories in Europe.

Prospects for Ukraine’s grain planting in tatters

Ukraine and parts of Russia are blessed with black earth, which makes them the world’s breadbasket. Between them, they account for almost a third of all global wheat exports. Ukraine alone contributes 15% to all global corn and rapeseed shipments. Global agricultural inventories are already very low due to previous crop issues in drought-hit Latin America. In Ukraine, the corn and wheat planting season will start in four to six weeks, an unlikely prospect given rising diesel prices and the damage done to roads, ports, and bridges. While European countries will be able to deal with accelerated food inflation, wheat-importing economies like Egypt or many African countries are in a much weaker position. Let’s also not forget that grain production may fall in other parts of the world as well because fertilizer prices tripled last year. And here, we have another problem: Ukraine and Russia are among the biggest fertilizer exporters.

From a strictly rational perspective aimed at mitigating inflationary and geopolitical risks in a portfolio, it seems reasonable to hold a position in commodities, an asset class that has rallied by 26.5% so far this year. Putting away our investing hat, we stand aghast at the human tragedy unfolding on our doorstep.

1. All percentage changes as of March 1, 2022.