Why Investors Should be More Selective with Consumer Packaged Goods Stocks

Quality Growth Boutique

Gillette’s men’s razor business used to be a market-share machine. With innovations, such as the three-blade Mach 3, followed by the five-blade Fusion, and a marketing budget that dwarfed rivals, the Procter & Gamble division held 70% of the US market in 20101. But by 2016, Gillette’s share had plummeted to 54%.2

What happened was a warning call to major consumer packaged goods (CPG) makers. In that time, two razor start-ups caught Gillette completely flat footed. With purely e-commerce models and convenient subscription services, Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club caused most of Gillette’s share loss3.

The rise of these upstart brands underscores a seismic shift in the CPG industry over the last decade. Once protected by big TV ad budgets and a lock-hold on store shelves, many CPG companies have seen their major barriers to entry crumble. Aided by social media, e-commerce, contract manufacturing and even the desire of once-faithful retailers to sell more exciting products, startup brands are increasingly taking share from legacy CPG companies.

Meanwhile, retailers – armed with their own consumer data –are taking share from another angle. They are launching far more sophisticated private-label brands that are equal to or better than national brands in quality and innovation. And they can have as much or more brand equity than their national counterparts. Consider Costco’s Kirkland brand. With $52 billion in sales annually, it would have a market cap of $76 billion if valued alone,4 or half of Costco’s total valuation.

When the walls around big brands fell, many CPG companies were caught off guard. During the past few years, some have been far faster to adapt than others. As a result, investors must be far more selective in choosing CPG stocks. To succeed in this new landscape, established CPG companies need to be more nimble. They must be more aggressive in managing their brand portfolios. That means being faster at jettisoning laggards and in acquiring small brands themselves to counter the small-brand threat – all with a disciplined eye for maximizing shareholder value. And they must be more digitally astute about what consumers want. Nestle is an example of a CPG company that has taken all these actions.

Our view is that if chosen astutely, CPG companies still play a valuable role in portfolio construction: They can offer significant downside protection when economic times are tough. But long gone are the days when investors could nearly throw darts to pick CPG stocks. In the forty years preceding 2010, the group outperformed every business sector in the S&P 500 index except one.5 In the last decade, however, the group has underperformed the index by two percentage points a year.6

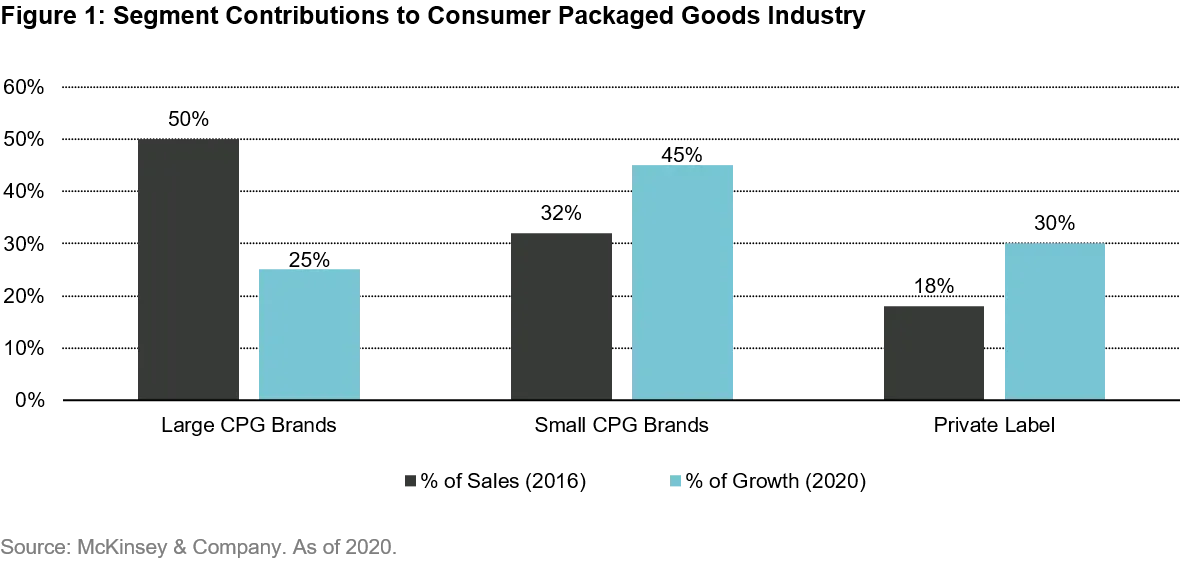

One only needs to look at the growth of small brands and private label to find the cause of that underperformance. While big brands accounted for 50% of US CPG sales at the beginning of 2016, they only made up 25% of the industry’s growth through 2020.7 Small brands, by comparison, only accounted for 32% of sales in 2016, yet they drove 45% of all CPG sales growth during the same period, nearly double that of big brands.8 Private label, meanwhile, accounted for 18% of CPG sales in 2016. Yet private label captured 30% of growth, surpassing the performance of big brands as well.9

Social media, e-commerce, and contract manufacturers open doors for small brands

The Internet and advent of e-commerce and social media opened the door to small brands. They knocked down barriers of hefty TV ad budgets and dominant shelf placement that protected big CPG brands. These barriers made it too costly for small brands to enter the market. But with social media, start-up brands could build brand awareness for free by telling a story around their brands. With digital advertising they could reach a much more targeted audience at the fraction of the cost of traditional advertising. Forget brick and mortar. Start-ups could launch sales on their own e-commerce sites or on platforms like Amazon.

When start-up Quip launched its sleek and compact electric toothbrush at the end of 2015, it created a homepage on Facebook to tell the brand’s story, while opening its own e-commerce site to sell its brushes. It spent a fraction of its total $300,000 start-up budget on Facebook ads to draw traffic to the site.10 If it had used TV, it would have spent one third of that budget, or $115,000 for a 30-second commercial on a national network, not counting production costs.11 Quip generated 100,000 brush sales in its first year.12 Today, it has 5 million users.13 “Facebook removes all kinds of barriers to entry for small companies,” says Shane Pittson, Quip’s head of marketing.

A subindustry has formed catering to the needs of small brands and helping them to grow. There are contract manufacturers like International Products Group (IPG) in Cleveland. Founded by a former L’Oreal executive, it targets small personal-care and beauty brands. IPG will take an equity stake in brands that it views as promising and helps with product design and marketing. There are also product brokerage firms, like Bdirect Cos. of Los Angeles, that specialize in helping small brands get off the ground and sell on Amazon and into retail chains. It provides brands with outside management expertise. It is also affiliated with private-equity firms that invest in these brands mid stage. And it has ties with major CPG firms, like Unilever, which are eager to buy successful small brands once they hit sales over a certain threshold. For example, Unilever bought Seventh Generation natural cleaning products for about $700 million out of Bdirect’s stable of brands. Dr. Pepper Snapple bought the drink brand, Bai, for $1.7 billion.

In fact, the hope for a lucrative payout is the biggest factor driving the formation of start-up brands. While roughly 80% of new CPG products fail, the number of start-ups keeps growing, as the number of exhibitors at the nation’s largest trade show for small brands demonstrates.14 Exhibitors at the 2019 Natural Products Expo West convention, the last before the pandemic, totaled 3,600. That’s nearly double 2010. For most big brands, small brands are the commercial equivalent of death by a thousand cuts. Most of these brands may fail, but they keep coming in greater numbers, collectively taking share from big brands on the margin.

Capturing the next generation with digital sales and consumer data

Small brands have competitive advantages over national brands. Because most start-up brands rely on digital sales and marketing channels, they have an advantage over legacy brands in reaching younger shoppers who thrive on searching for new and unique products on the web. Baby Boomers are still the biggest customers of established brands and they have been slower to adapt to the internet. This puts legacy CPG companies in a bind. If they shift more of their ad budgets away from TV to digital, they risk losing their core customers. TiVo Research estimates that for every $1 cut in TV ad spending, legacy CPG companies lose $3 in revenues.15 This has given smaller brands a leg up in capturing the next generation of shoppers.

Digital marketing and sales channels give small brands another, far greater advantage – granular information about their customers. Big brands, selling through brick-and-mortar chains, get little of this information. That’s because retailers are loath to share it. Without this information it is more difficult for big CPG companies to develop new products that finely meet consumers needs or see new product opportunities.

When Gautam Gupta founded healthy snack company Nature Box in 2012, he saw a market niche. Big CPG snack companies were too slow to move in a healthy direction. He specifically targeted customers in the 30- to 35-year old range because they are more likely to try a new brand and search online. “Older shoppers may tend to stay with big brands, but younger shoppers are moving away from them,” he says. He launched sales on his own website, Naturebox.com, using contract manufacturers to cut capital outlays. By closely analyzing the site’s sales data, Gupta could see what snacks its customers liked and disliked. It used this data to develop more appealing snacks. Better yet, it asked customers on its website for product ideas which gives them a sense of ownership and greater bond with the brand.

Then Nature Box started taking shelf space in brick-and-mortar stores, a transition that is happening with increasing frequency these days to the detriment of big brands. By selling online first, Nature Box established that it had a successful brand. When Gupta went to pitch major retailers, he could even show them which particular snacks were selling best in which particular regions. That saved a step for retailers, making the brand more attractive, since they didn’t have to determine which products to sell where. Now Nature Box is in national chains, like Target and Kroger, and regional chains, like Wegmans in the Northeast and HEB in Texas.

The fact is mass retailers increasingly want small brands. Every retailer can sell established CPG brands. That’s the problem. It does nothing to differentiate their stores from the competition, leaving lower prices as the biggest lever to draw consumers. Bringing in small brands helps retailers spice up their merchandising mix. The products generally offer more innovation than national brands. And retailers can earn higher margins on them. Target was the first mass retailer to follow this strategy. In 2016, it brought in Harry’s razors and blades.16 In the last five years, it has added over 100 small brands, including Quip17. Walmart and Kroger are following suit.

Private label is another force cutting into big-brand sales

While small brands chip away at sales of legacy CPG players from one direction, store private label is from another. Retailers no longer simply view store label as a cheaper alternative to national brands on which they can command higher gross margins. They see it as strategic way they can differentiate their stores and increase consumer loyalty. Online competition has necessitated this, as has the over-crowded brick-and-mortar landscape, where there are fewer distinctions between major chains. Big CPG companies are also to blame. Faced with slowing volumes over the last decade, they have increasingly leaned on price increases to boost revenue. This has created a wide window where retailers can more easily undercut national brands with lower, private-label pricing.

Armed with their proprietary consumer data, retailers now develop private label with the same sophistication of CPG companies. For instance, to launch its health-conscious, Good & Gather food brand in 2019, Target used numerous datasets.18 Its biggest insight was that Target shoppers’ definition of healthy revolved most around the elimination of artificial flavors, synthetic colors, artificial flavors and high-fructose corn syrup.19 Launched under advertising tagline – “A new way to eat well every day” – the clean-label offering of 650 items posted sales of $1 billion the first year.20 That growth would be a home run for any CPG company product launch.

Target’s success is not an isolated event. Kroger’s Simple Truth organic food line, launched in 2012, hit $1.6 billion in sales in three years.21 The US’ fastest growing food retailer, German-owned Aldi, almost exclusively sells private label at its 2000-plus stores.22 The same at Trader Joe’s, which is also German held. After a relaunch in 2009, Walmart’s Great Value offering of food and household products nearly tripled in sales to about $27 billion in fiscal 2020.23 Costco’s Kirkland brand also tripled to $52 billion during that time. To put Kirkland’s size in perspective, Procter & Gamble needed 65 brands to generate $71 billion in sales in fiscal 2020. Kirkland’s growth, meanwhile, came at the expense of national brands within Costco. In the last decade, Kirkland’s percent of total Costco store sales rose to 32%, from 20%24.

Private-label brands now rival national brands in terms of brand equity – they are no longer generic stepchildren. Consumer trust that private label is every bit as good or better than national brands rose to 89% in 202025, up from 85% in 201926. Costco’s Kirkland branded bacon, for instance, beat 14 other national brands in blind taste tests27, and Kroger’s three private label brands consistently rank higher in Net Promoter Scores than national-brand competitors.28 Private label has closed the quality cap with national brands, while remaining cheaper, an average of 29% lower.29

Nestle – Actively adjusting to the new reality

Given these headwinds, the CPG industry has become a more complex space to invest. Choosing CPG stocks is much more of a bottom-up exercise than it has ever been. This is now a more dynamic industry, due to the rise of successful small brands and private label. There are, however, still large brands that are winners. Our view is that these are companies, like Nestle, that have been actively responding to this new competitive landscape.

Nestle has become far more active in pruning its product portfolio in response to these forces in the last five years. For example, it divested its bottled water brands in lower priced categories, where a quarter of the market is controlled by private label.30 It kept premium water brands such as San Pellegrino, which face less private-label competition because of their strong brand names. Similarly, it sold its Skin Health business to focus on its core food business and entered joint-ventures for its ice-cream and European cold cuts businesses.

As it disposes of laggards, Nestle is buying upstart brands in fast-growing, new categories. In 2017, it bought Sweet Earth, which makes a variety of vegan frozen meals in the “plant-based meat” segment, which is growing at double digits.31 It has left Sweet Earth’s management independent to preserve the company’s entrepreneurial culture, while providing additional manufacturing capacity so it can grow faster. At the same time, it is also reallocating larger amounts of capital to categories that are fast growing and where it is easier to differentiate versus private label. This is evident in the vitamin, mineral and supplement space with acquisitions, such as Atrium, Vital Proteins and brands from The Bountiful Company. It is also evident in the coffee space, where Nestle was already the global leader, with the rights to Starbucks outside of Starbucks stores.

Nestle is also working to improve its digital capabilities and appeal to younger customers. It has invested heavily in internal IT systems to capture consumer data from across all its brands to sharpen product development and marketing. This helps offset the data gap with retailers. It has acquired the online-only brands Persona, which makes personalized vitamins and supplements, and Tails.com, a customized pet food company. Both sell direct to consumers on their own websites on a subscription basis, giving Nestle another big source of customer information. At the same time, the acquisitions and large investments have helped expand Nestle’s online sales and capabilities. From 5% of sales in 201632 it grew to high single digits in 2019 and readied the organization for the COVID induced push to 13% of total sales in 202033, a percentage that has continued to rise in 2021. This is helping Nestle reach younger shoppers. And Nestle has been very active in ESG, which helps cement relations with younger generations further.

Nestle is one example of how some CPG companies can transform to operate successfully in this new environment. In the meantime, we believe the stock still offers downside protection during market sell-offs, such as during the Great Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 crash.

In conclusion

For CPG, as with many industries, we have seen disruption in historical barriers to entry over the past decade. The changes in how media is consumed, where people shop, how products are made, and which products are trusted require the old playbook to be rewritten. It isn’t a gross exaggeration to say that the industry overall was not ready to face this challenge a decade ago. Since then, we have seen some players adapt, and others left behind.

For quality growth managers, therefore, the investible universe in the CPG sector is much narrower than it once was. Without change, many once great CPG companies cannot be counted on to show even modest growth. Investors cannot simply buy an ETF to get exposure to a sector that historically let investors sleep well at night. An investor today should assess how each company has been transforming to meet the new reality and not rely on past brand strength. The organization needs to be more agile with new ways of using media, data, and production, while the brand must be differentiated and innovative enough to stand up to new competition.

Any investments discussed are for illustrative purposes only and there is no assurance that the adviser will make any investments with the same or similar characteristics as any investments presented. The investments are presented for discussion purposes only and are not a reliable indicator of the performance or investment profile of any composite or client account. Further, the reader should not assume that any investments identified were or will be profitable or that any investment recommendations or that investment decisions we make in the future will be profitable.

Certain of the information contained in this viewpoint is based upon forward-looking statements, information and opinions, including descriptions of anticipated market changes and expectations of future activity. VAMUS believes that such statements, information, and opinions are based upon reasonable estimates and assumptions. However, forward-looking statements, information and opinions are inherently uncertain and actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected in the forward-looking statements. Therefore, undue reliance should not be placed on such forward-looking statements, information and opinions.

1. Andrew Menke, Global Edge, 1/27/2020, “The Not so Smooth Future of the Global Razor Market”

2. Sharon Terlep, Wall Street Journal, 4/4/2017, “Gillette, Bleeding Market Share, Cuts Prices of Razors”

3. Sharon Terlep, Wall Street Journal, 4/4/2017, “Gillette, Bleeding Market Share, Cuts Prices of Razors”

4. Michael Lasser, UBS, 3/22/2019, “UBS Evidence Lab inside: COST/BJ/Sam’s – Deep Dive Into The Clubs”

5. Udo Kopka, Eldon Little, Jessica Moulton, Rene Schmutzler, and Patrick Simon, McKinsey & Company, 7/30/2020, “What got us here won’t get us there: A new model for the consumer goods industry”

6. Udo Kopka, Eldon Little, Jessica Moulton, Rene Schmutzler, and Patrick Simon, McKinsey & Company, 7/30/2020, “What got us here won’t get us there: A new model for the consumer goods industry”

7. Udo Kopka, Eldon Little, Jessica Moulton, Rene Schmutzler, and Patrick Simon, McKinsey & Company, 7/30/2020, “What got us here won’t get us there: A new model for the consumer goods industry”

8. Udo Kopka, Eldon Little, Jessica Moulton, Rene Schmutzler, and Patrick Simon, McKinsey & Company, 7/30/2020, “What got us here won’t get us there: A new model for the consumer goods industry”

9. Udo Kopka, Eldon Little, Jessica Moulton, Rene Schmutzler, and Patrick Simon, McKinsey & Company, 7/30/2020, “What got us here won’t get us there: A new model for the consumer goods industry”

10. Elizabeth Segran, Fast Company, 04/03/2018, “This Startup Built Its Brand On Facebook. Now It Can Never Leave.”

11. Kelly Main, Fit Small Business, 01/21/2021, “Everything You Need to Know About TV Advertising Costs”

12. Paul Sawers, Venture Beat, 11/1/2017, “Toothbrush subscription service Quip raises $10 million”

13. Diana Pearl, Adweek, 12/3/2020, “Quip Expands Into Gum With Its First Major Product Extension”

14. Katy Askew, Food Navigator, 3/18/2019, “Most new products fail: Implicit sensory testing can help beat the odds”

15. EGTA, 3/2017, “Decreased TV advertising spend hurts sales”

16. Target Corporate Release, A Bullseye View, 8/3/2016, “Harry’s is Coming to Target! The Shave Brand’s Co-CEOs and Target’s John Butcher Talk Shop”

17. Target Accelerators Programs Alumni

18. Jessica Dumont, Grocery Dive, 9/16/2019, “Target looks to Good & Gather to define grocery business”

19. Category Management Association, 10/4/2019, “We Unpack Stephanie Lundquist’s Landmark Keynote and the New Brand Launch”

20. Category Management Association, 10/4/2019, “We Unpack Stephanie Lundquist’s Landmark Keynote and the New Brand Launch”

21. Eric Schroeder, Food Business News, 6/28/2021, “Kroger exec: ‘We go to market in a variety of ways’”

22. Mike Troy, Progressive Grocer, 8/17/2020, “Aldi CEO on Being America’s Fastest Growing Grocer”

23. Jack Neff, AdAge, 9/7/2009, “Why Walmart’s Great Value Changes The Game”

24. Costco Annual Report 2020

25. Daymon Private Brand Intelligence Report 2020, 8/2020, “The Future of Private Brands”

26. Krishna Thakker, Grocery Dive, 4/12/2019, “Shoppers want more premium private label products, report says”

27. Consumer Reports, 9/2013, “Which brand is making the best bacon”

28. Kroger Investor Meeting, 11/5/2019

29. Hannah Karp, Wall Street Journal, 1/31/2012, “Store Brands Step Up Their Game, and Prices”

30. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Global Database, 5/2020, “Sales of branded and private label flavored water in the United States in 2019”

31. PR Newswire, 3/16/2021, “Plant-based Meat Market Size To Reach $13.8 Billion By 2027, Owing To Rising Adoption Of Vegetarian Eating Habits Among Fitness Aware Consumers | Million Insights”

32. Nestle Full Year 2016 Results Press Release

33. Nestle Full Year 2020 Results Press Release