Is China’s “Japanification” on its way?

Multi Asset Boutique

Key takeaways

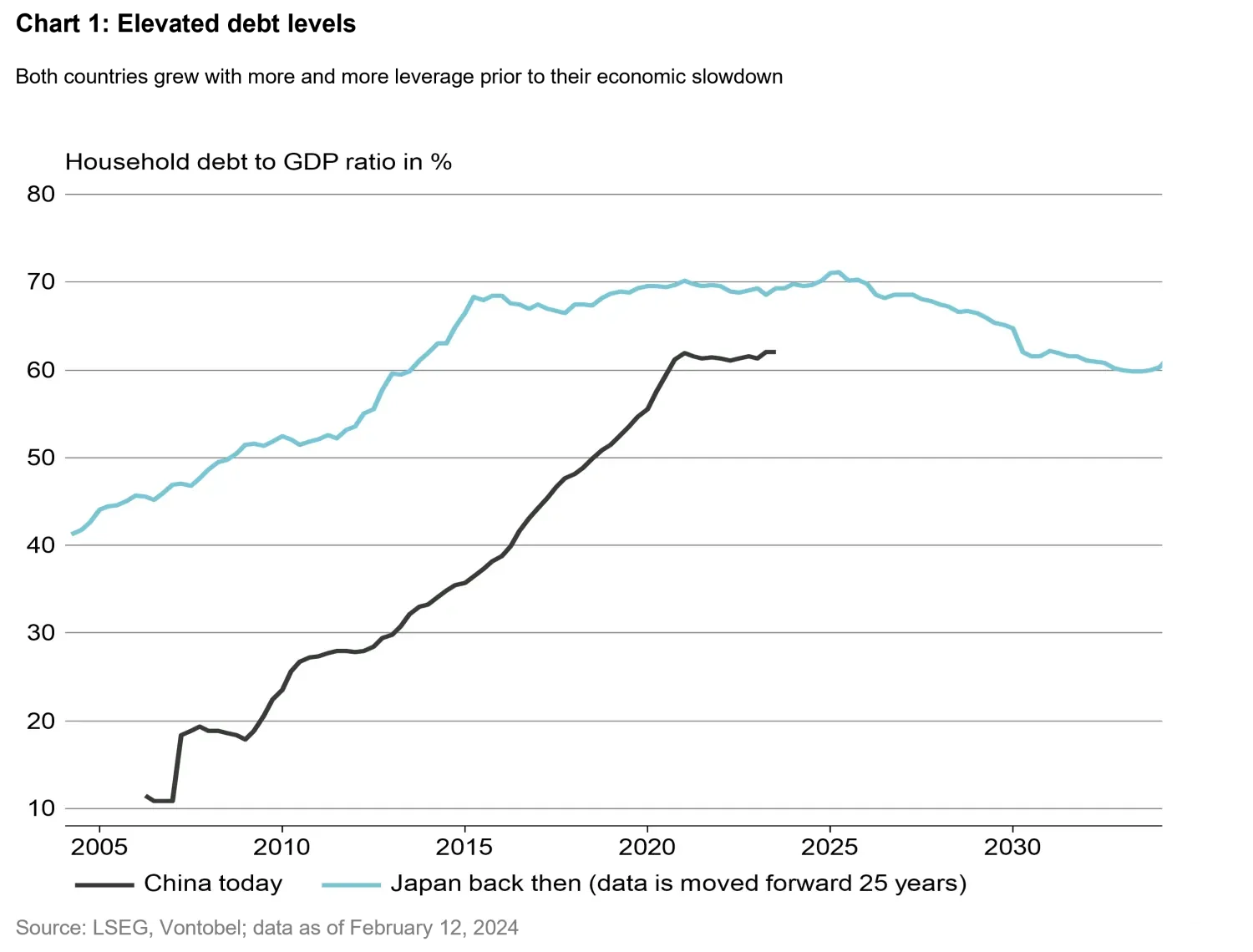

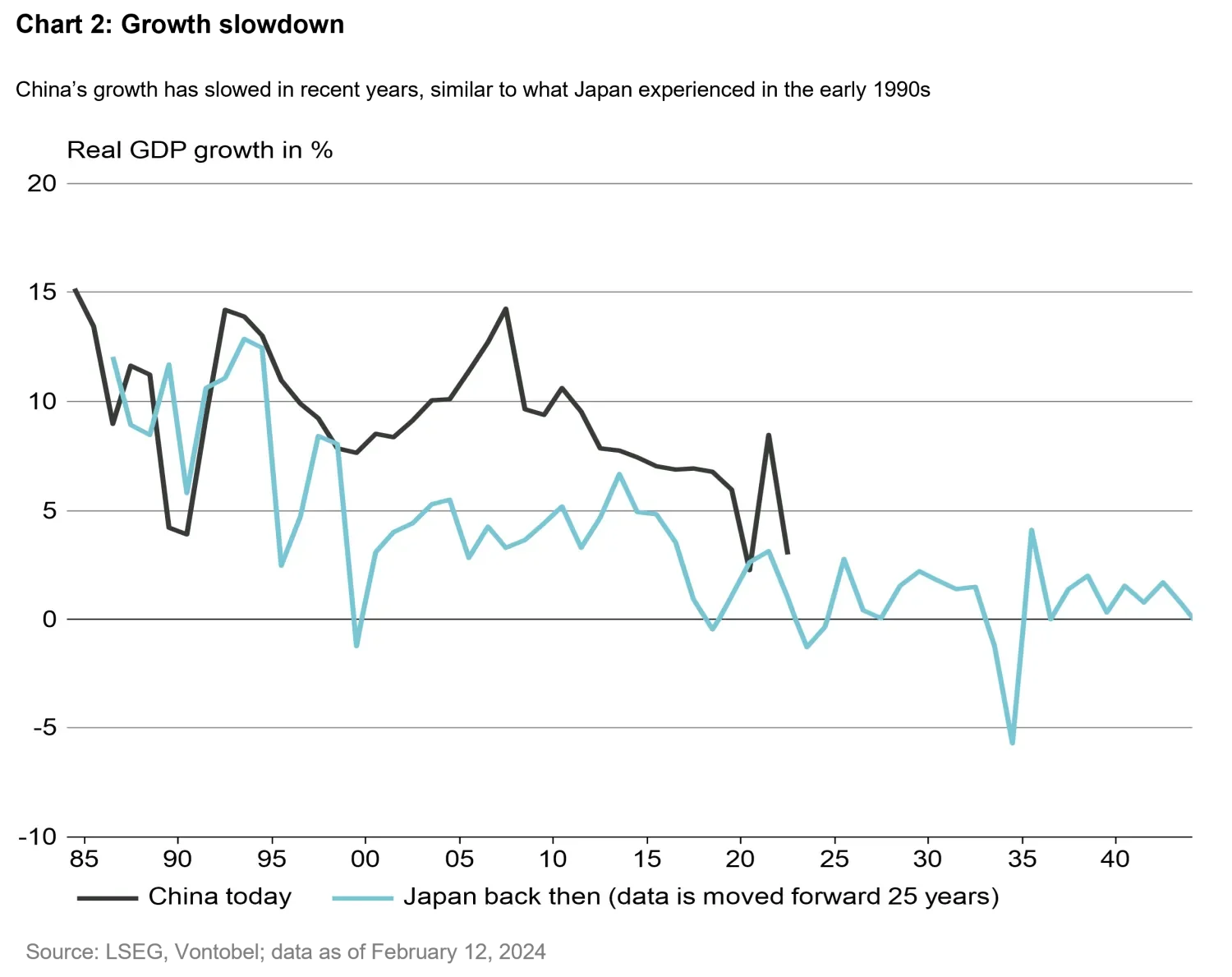

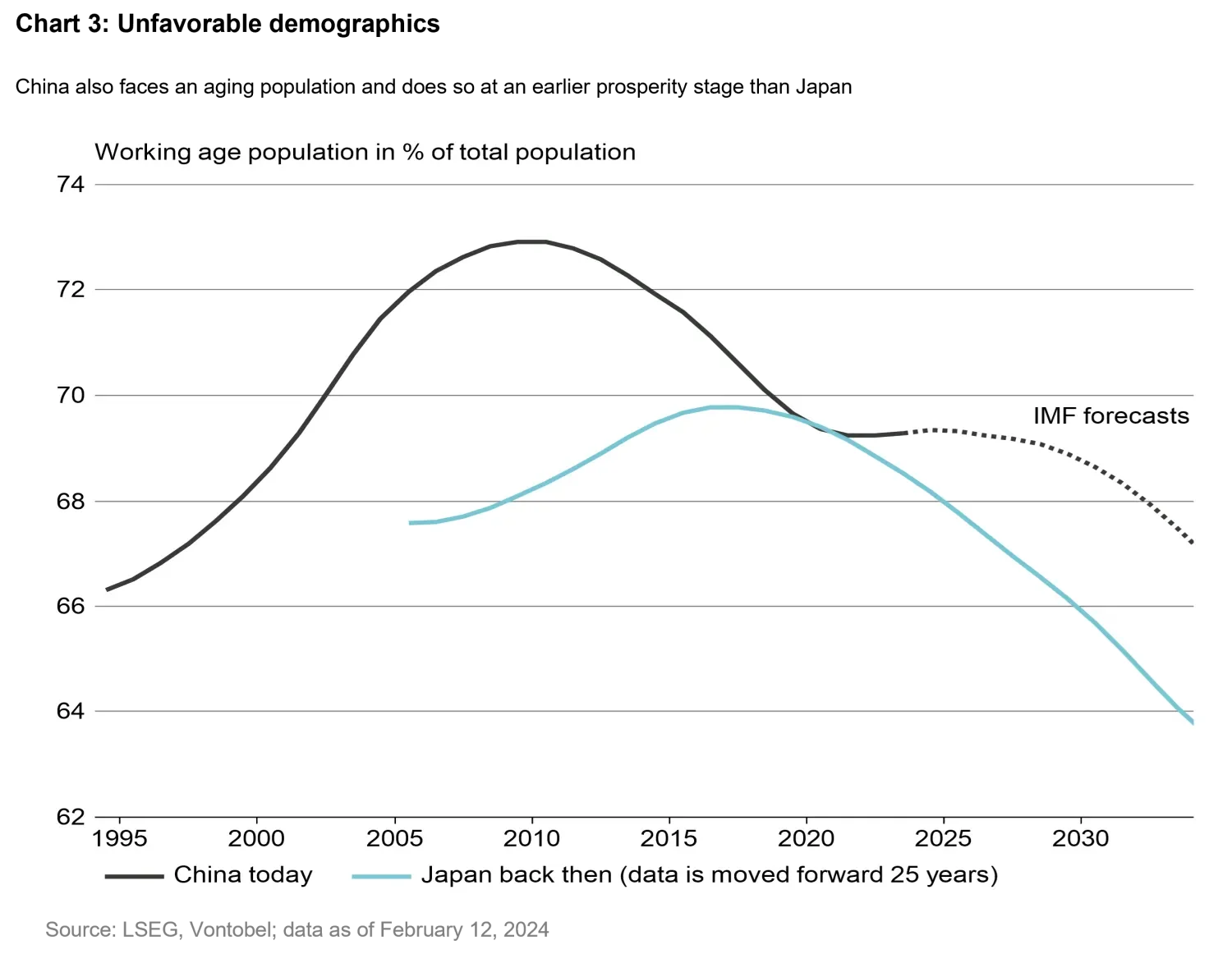

- There are similarities between China today and Japan in the 1980s and 1990s, such as the high level of debt, the state of China’s real estate market, and unfavorable demographic trends.

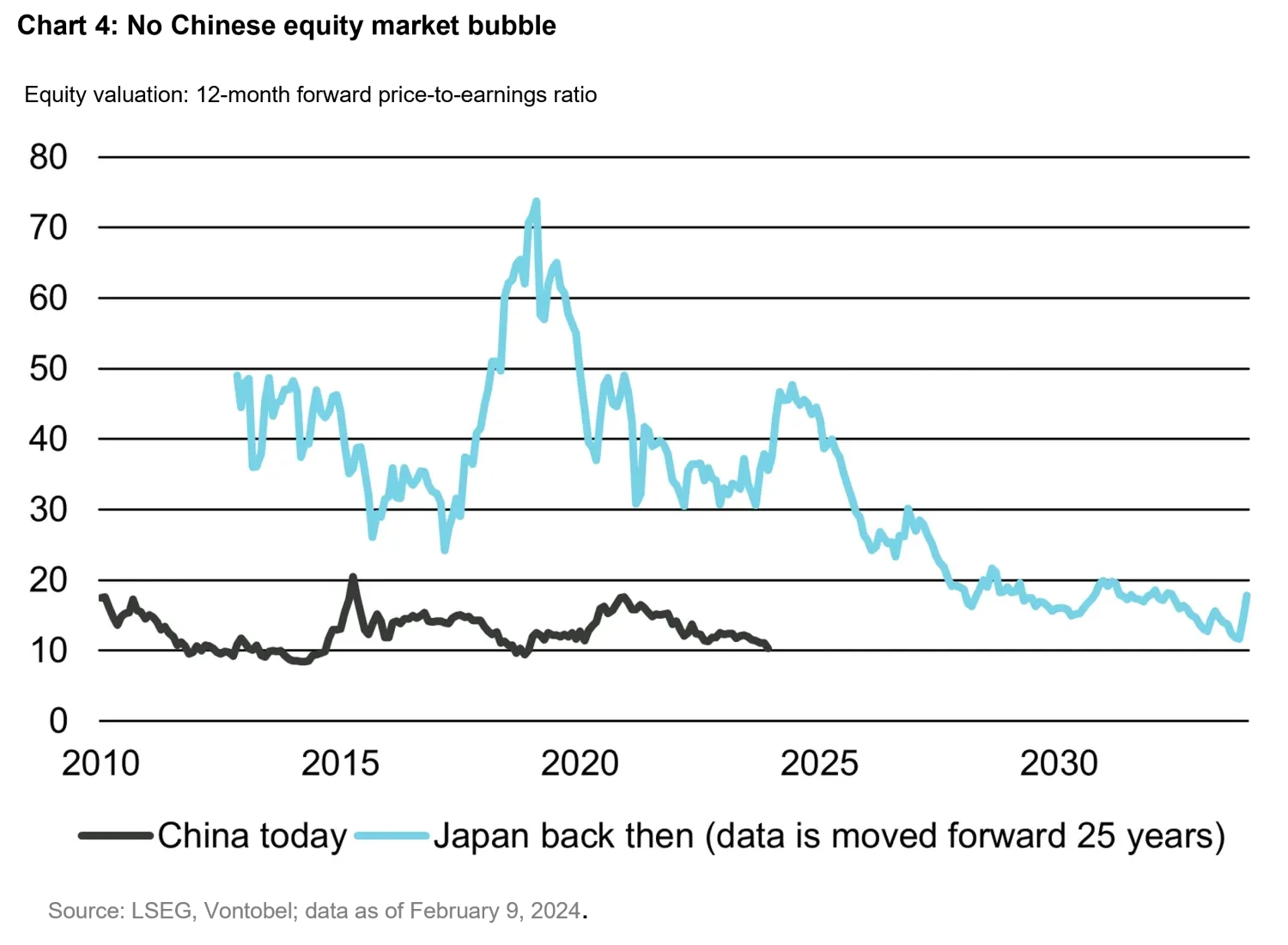

- While we count several parallels between China today and Japan in the 1980s and 1990s, it’s not a one-to-one comparison. There are differences in its stock market environment and currency trends.

- Should China face the same situation as Japan, it would reverberate throughout the global economy, given China’s much higher contribution to the world’s GDP and its importance for commodity markets.

Sony’s Walkman as a coveted technology gadget. Nintendo’s early gaming consoles that made children’s hearts beat faster. Along with Toyota’s and Honda’s cars making their way onto the world’s streets, these Japanese success stories were the embodiment of a phoenix rising from the ashes after the country’s industry was almost completely destroyed during World War II. But the economic miracle didn’t last, resulting in the “Lost Decade” and China subsequently taking its place as the world’s second-largest economy. Comparing the Japan of yesteryear with today’s China raises the question whether China could soon face a similar fate.

Japan experienced an economic boom after World War II up to the early 1990s. In 1988, Japan’s theoretical land value exceeded all of that in the US (which is almost 25 times the size of Japan) by a factor of four to five, and real estate prices climbed to dizzying heights. A year later, eight of the world’s 10 largest companies by market capitalization were domiciled in Japan, and the Nikkei 225 stock index soared from one high to the next.

Japanese companies also made bold moves abroad at the end of the 1980s, with Mitsubishi Estate Co. acquiring a 51 percent majority stake in the Rockefeller Group Inc., which owned the Rockefeller Center and other high-profile properties in midtown Manhattan.

Bank of Japan (BoJ) policymakers were concerned about the overheated economy, though mostly stayed on the sidelines, especially in the aftermath of the 1987 Black Monday shock. But one week after Yasushi Mieno took office as Governor of the BoJ at the end of 1989, he raised interest rates, saying the move would contribute to sustainable growth driven by domestic demand while simultaneously maintaining price stability. More hikes followed over months. Then, the Japanese asset bubble burst, triggering a balance sheet recession1 and ushering in the “Lost Decade”. The Nikkei 225 lost almost two- thirds of its value by 1992, while real estate prices plummeted around 70 percent by 2001.

China as the “Japan 2.0”?

There are similarities worth considering, such as the high level of debt. In the 1990s, Japanese household debt amounted to almost 70 percent of GDP. China’s debt has swelled to 62 percent in the third quarter of 2023 (the latest available data) from around 11 percent in the early 2000s (see chart 1).

The state of China’s real estate market evokes memories of what transpired in Japan. Property developers’ heavily leveraged business model has come under pressure after years of soaring Chinese house prices, and a Hong Kong court in January ordered the liquidation of troubled real estate developer Evergrande. A further escalation of the crisis could have a drastic impact, as the real estate market accounts for almost 30 percent of China’s GDP.

China’s GDP growth is expected to slow to 4.6 percent this year and to 3.5 percent in 2028, from around 5 percent in 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund (see chart 2). This is also reflected in lower price pressure, with signs mounting that China faces even more deflation. Lower prices may be positive at first glance, but harbor the risk that consumers postpone purchases in anticipation of even lower prices and thus of a deflationary spiral, as has been seen in Japan for decades.

Both countries are grappling with unfavorable demographic trends, such as a shrinking working population. Japan’s fertility rate (number of births per woman) peaked in 1967 at 2.2 and has fallen continuously since then, dropping to 1.5 in the early 1990s and remaining at 1.3 since 2020. China’s latest available fertility rate (2021) is even lower, at 1.2 (see chart 3).

Deteriorating US-Chinese relations over the last few years (trade war, “near-shoring” or “friend-shoring”, etc.) is also reminiscent of Japan, which faced increasing US criticism for unfair trading practices.2

What speaks against a Japanification of China?

For one, the Chinese economy appears to be struggling primarily with a hot real estate market, but not with a hot stock market. The Nikkei 225 was trading at 70× price to earnings (P/E) at the height of the Japanese bubble, while the Shanghai Composite is currently trading at around 12× (see chart 4).

The Japanese yen appreciated 20 percent in just a few months after the 1985 Plaza Accord.3 That’s not the case for the Chinese yuan, which, unlike the free-floating yen, is pegged.

Despite its growing influence in the world, China is still an emerging market. Developments like years of increasing urbanization speak against a Japanification of China as it’s often associated with higher economic growth. And finally, Chinese decision-makers do have one advantage: they can draw lessons from Japan’s economic history.

Food for thought

While we count several parallels between China today and Japan in the 1980s and 1990s, it’s not a one-to-one comparison. Should China face the same situation as Japan, it would reverberate throughout the global economy, given China’s much higher contribution to the world’s GDP and its importance for commodity markets. China will probably have to bolster the economy with a supportive fiscal policy rather than via monetary policy (see chart 5).

1. A balance sheet recession is a period characterized by deflation and weak growth and occurs when high levels of private sector debt lead to a slowdown or decline in economic growth amid a focus on repaying debt rather than investing or spending. According to economist Richard C. Koo, fiscal policy, not monetary policy (i.e., rate cuts), should be used to fight a balance sheet recession.

2. Source: Article by Bruegel think tank, “Will China’s trade war with the US end like that of Japan in the 1980s?”, published May 13, 2019.

3. An agreement between France, West Germany, Japan, the US, and the UK to weaken the overvalued US dollar.