How to prep your bond portfolio for recession

TwentyFour

At the beginning of this year you would have struggled to find a single investment bank or asset manager (ourselves included) that thought owning 10-year US Treasuries (USTs) was a good idea. As we wrote in January , inflation was at that time making a mockery of central banks’ ‘transitory’ rhetoric and we thought government bond yields were set to scream higher, making 10-year USTs deeply unpopular among the people whose job it is to tell investors where to put their money.

That all changed on April 7 when Barclays strategists published a note entitled ‘Go long 10y US Treasuries’, and a handful of others have since followed suit; the world’s favourite safe haven asset looks to suddenly be back in fashion, and that is because for some, recession is now looking more likely and less far away than it did a few weeks ago.

In our view it is time for investors to think about gradually preparing their portfolios for this risk. In short, we think building a position in 10-year USTs is now a serious consideration for bondholders, as is gradually increasing credit quality and focusing on shorter dated bonds in the coming months in order to try to get maximum benefit from the higher yields on offer in fixed income today.

Inflation will outstay its welcome…

If the probability of recession is rising, it is because the Fed’s chances of engineering a soft landing for the US economy look to be shrinking with every month that inflation remains well above target.

In our January piece we highlighted that we thought central banks were clearly behind the curve as 2021 came to a close, but inflationary forces have proved to be even stronger than they were when the Fed performed its hawkish ‘pivot’ back in December. US consumer price inflation (CPI) climbed again to a mammoth 8.5% in March, but the bigger problem is that this was the 12th consecutive monthly reading above 4%. Consumers – the driving force of every developed economy – are being squeezed from every conceivable angle, from a recent surge in the price of palm oil to ongoing supply chain disruption from COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, not to mention a huge spike in energy prices.

The next squeeze is monetary tightening in the form of interest rate hikes and the Fed’s balance sheet reduction, and in our view this is chiefly where recession fears are coming from. Inflation has forced investors to price in a very aggressive rate hike strategy from the Fed and other central banks in the coming months; the big question is whether a soft landing can be achieved with rates rising at such a pace.

Deutsche Bank economists think not. In a report at the end of April they said a US recession was not only likely, but that it would be “worse than expected,” with core inflation running at 4-5% well into 2023 and receding only after the recession.

…and speed us into late-cycle

Our view is less pessimistic; we would put the chances of a US recession in 2023 at less than 50%, based mainly on the evident strength of the economy coming into 2022, which has so far provided an adequate buffer to the shocks listed above.

However, while views like Deutsche Bank’s are becoming more prevalent in the media (which tends to favour dramatic headlines), we are yet to see a looming recession show up in hard economic data. Consumer confidence has taken a hit of late, but gross retail sales have held firm and the Q1 earnings season has shown US and European corporates have been navigating these obstacles from a position of strength, with profit margins growing and a healthy percentage of firms beating estimates.

That said, we feel that the rate hikes currently expected, added to the tough 12 months consumers have already endured, will begin to impact business investment before too long, and put the economy firmly in late-cycle territory by the end of this year, by which point the strong GDP growth buffer we had in 2021 will likely have been eroded. We think that will leave the economy (and the markets) more vulnerable to a further shock that could tip us from late-cycle into recession.

Time to start building a late-cycle portfolio

So how can we build a portfolio for recession?

Firstly it is very important to note that, as the previous cycle neatly demonstrated, late-cycle conditions can last a very long time indeed, during which time risk assets can still rally and get very expensive relative to long-term averages. Making your portfolio too defensive too quickly can be very detrimental in such circumstances.

In our view, the best approach is to stay very liquid so that we can respond quickly to try to take advantage of any further intra-cycle dips, while building in enough protection against a potential recessionary sell-off. Therefore we think a rough balance of 15% in rates and 85% in relatively short dated credit is about right for today’s environment.

Let’s start with government bonds, or ‘rates’ in bond market parlance. If like everybody else you were avoiding longer dated USTs completely coming into 2022, then we think that view is now worth revisiting. The inflation-induced rates sell-off has seen 10-year UST yields rise from 1.51% on January 1 to 2.95% as of May 5. At almost 3%, we think a lot of bad news (and a good number of rate hikes) is already priced into this yield, and it can be a valuable risk-off position for a portfolio in the event of any worse-than-expected economic data.

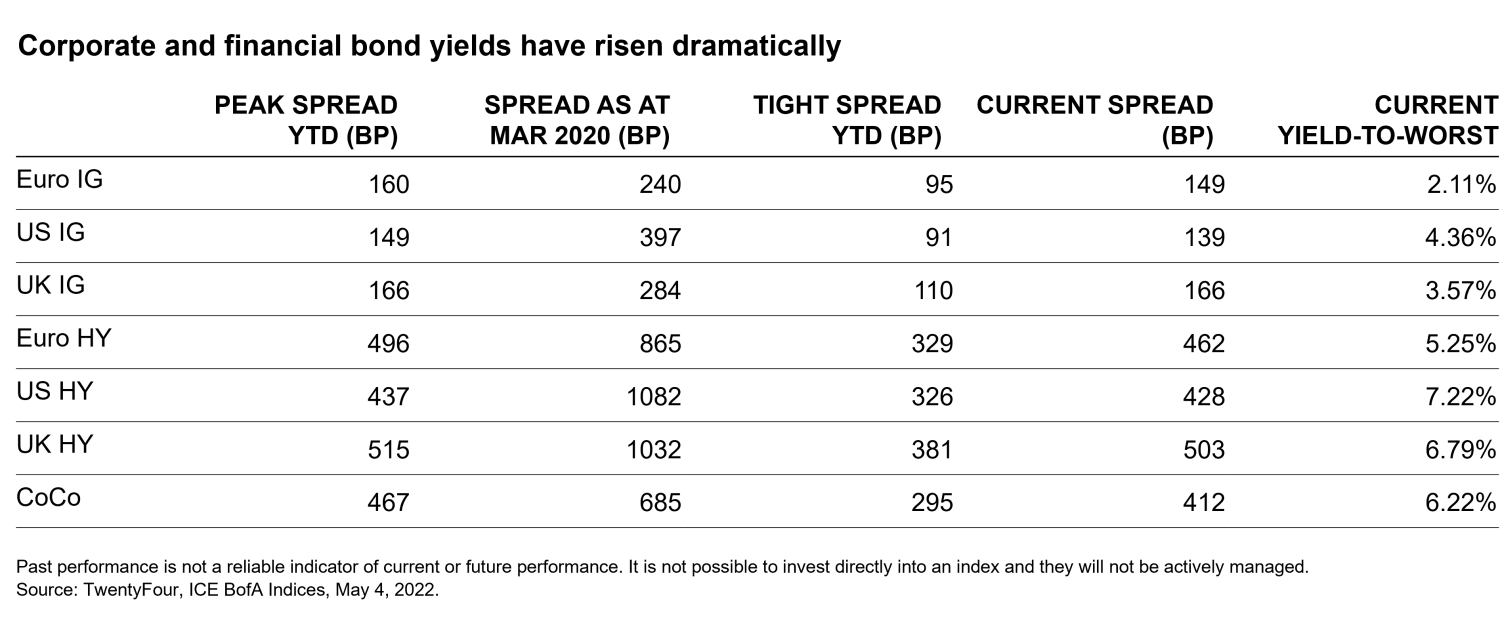

When it comes to credit, we want to maintain a high allocation but begin to favour higher credit quality and gradually decrease our overall credit duration by leaning towards shorter dated bonds, which should make the portfolio less exposed to any recessionary sell-off. Credit fundamentals remain strong with default rates still near record lows, but this isn’t a time to reach for risk in our view so we have moved up the ratings curve and we are avoiding CCC paper. We are also looking for companies able to pass on the rising cost of their inputs to customers without seeing a disproportionate drop in sales. For example, banks are extremely good at passing on costs to customers, as well as keeping a portion of each interest rate hike for themselves when they raise the interest rates on their own products. This makes the yield on subordinated bank debt (over 6% at the index level) look very attractive to us at the moment.

Fixed income has struggled in general so far this year, with the volatility in government bonds and geopolitical tensions leading to an aggressive widening in credit spreads. However, as the chart above shows, this does mean valuations in some sectors have dipped to levels not far off what we might expect to see in a recessionary environment, so we are shopping in a much cheaper looking bond market than we were in January.

In our experience those elevated yields can be a big help when navigating periods of volatility like the one we currently find ourselves in, since they give us confidence that we can still generate reasonable returns even if conditions worsen.

As a crude example, let’s take a simple bond portfolio that has a 15% rates allocation in 10-year USTs and 85% in credit, with a credit duration of 3.5 years and a starting yield of 7%. In a recession, if we assume a linear rally of 100bp in 10-year USTs, the rates allocation would contribute 1.5% to portfolio performance. If at the same time the yield on the credit allocation was to sell off by 200bp, meaning credit spreads would rise by 300bp (added to the underlying 100bp tightening in rates), then the portfolio would suffer a loss of around 6% from the credit allocation. Combining the rates and credit price moves we obviously get to -4.5%. However, over 12 months that number is more than compensated for by the starting yield of the portfolio (7%), resulting in a total return of around 2.5% on a one-year breakeven basis.

Ultimately, while we think recession (if it arrives) is many months away yet, in fixed income it is never too early to start preparing your portfolio for the risk.