Dispelling myths about sovereign distress and defaults. Case study: Russia and Sri Lanka

Fixed Income Boutique

Key takeaways

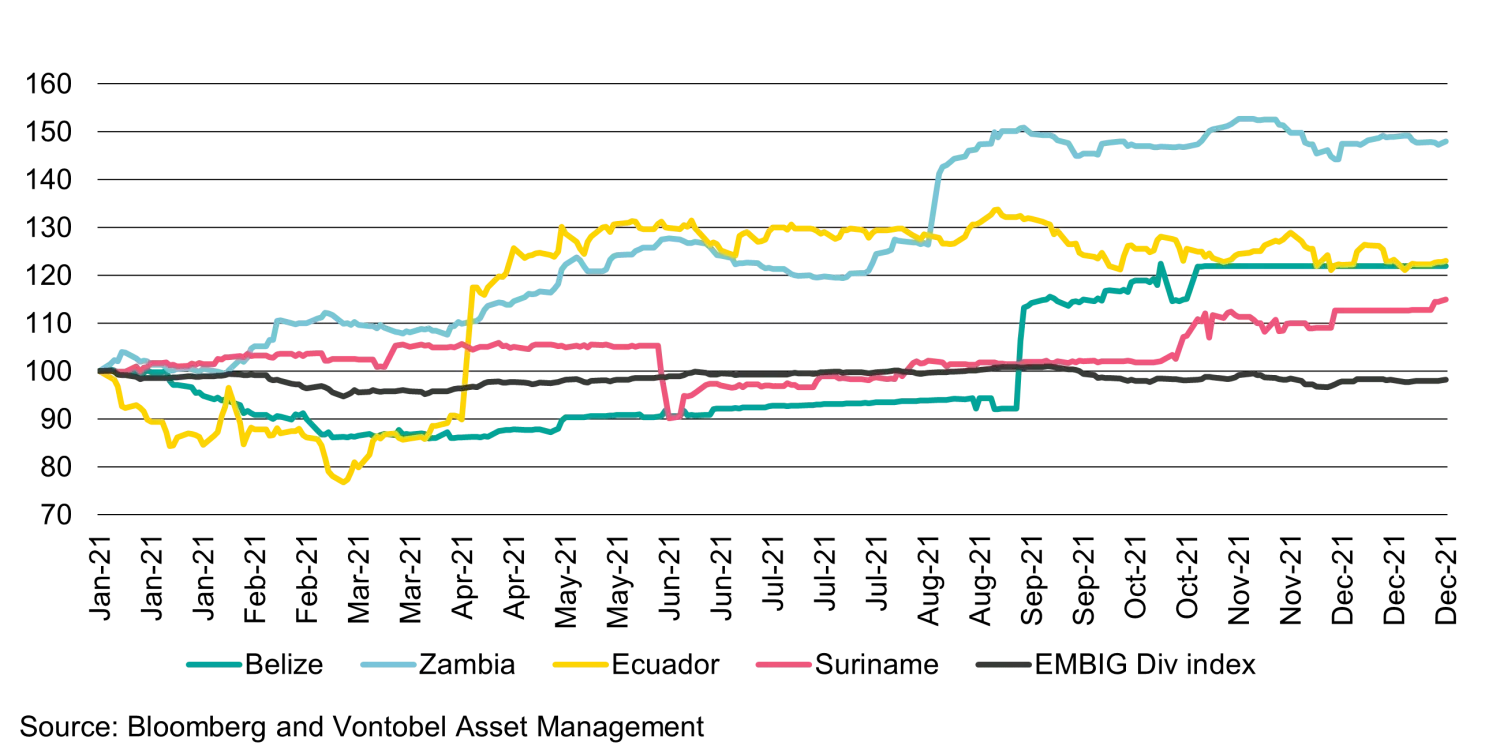

- Investing in distressed debt can be exceptionally profitable if you get the timing right. Three out of four of the top performing sovereigns in 2021 had defaulted previously.

- What those in power say will move markets. Often they get it wrong, creating opportunities for active investors.

- Default doesn’t mean zero. On average EM sovereign defaults realized 53% recoveries, albeit with broad variability.

- Investing in distressed debt can be highly profitable for those able to buy at deep discounts, at the expense of forced sellers.

- We believe that sanctions will force Russia into default and this may remain unresolved because sanctions will prevent restructuring.

- We expect Sri Lanka to default before its July 2022 bond maturity.

- An active approach plus an experienced team are key to unlock value from defaults.

Investing in distressed and even defaulted debt can be exceptionally profitable, especially if one gets the timing right. For example, last year, as the chart below shows, three of the top four best performing sovereigns were bonds that had defaulted: Zambia (+48%), Belize (+22%), and Suriname (+14.9%).

Defaulted and restructured bonds were the best performing sovereigns of 2021

Despite these impressive returns, sovereign defaults have become a more prevalent worry for investors since the onset of the pandemic given the additional burden that the crisis has put on most countries’ public finances. The war in Ukraine has only added to these worries.

We often receive questions from investors asking us about sovereigns in distress and defaulted bonds and their prospective recovery values. In this article, we discuss a few recent distressed-bond situations, some important concepts around sovereign defaults, and explain how investors can approach distressed sovereigns – those whose bonds trade with spreads above 1,000 bps.

Poisoning the well with words

Words matter, especially the words of those with power and influence. One example is the miscommunication debacle from the government of the Bahamas, which caused market mayhem last September. Following a statement from Prime Minister Philip Davis, Bahamas sovereign bonds dropped 13%. The New PM was asked by a journalist about a news article claiming that the Bahamas and Trinidad and Tobago would be the next Caribbean sovereigns to default. The article in question wasn’t well founded and markets would have probably ignored it were it not for PM Davis’ failed attempt to reassure investors. The PM said that the administration was “assessing the country’s debt arrangements and will seek to negotiate where necessary to avoid default.”

From an investor’s perspective the PM’s statement was contradictory because the terms of a bond contract can only be negotiated through a debt restructuring, and any debt restructuring is, by definition, an event of default. Thus, it’s not surprising that Bahamas bonds dropped on the PM’s comments as he was unintentionally saying that the Bahamas would restructure their debts. The government later clarified that they do not intend to restructure, and that the PM’s use of language was inappropriate. However, Bahamas bonds have continued to underperform in recent months despite the ongoing recovery in tourism, the island’s main source of FX revenues. Tourist air arrivals have already reached 83% of their pre-Covid level in Q4 2021. Therefore, we believe, the damaging rhetoric and low likelihood of default, combined with an improvement in the country’s economy, does not justify the low valuation.

Default doesn’t mean zero

A default rarely means that investors get zero, defaults are almost always followed by a restructuring. Formally, a default occurs when a debtor fails to make a timely payment of interest or principal as agreed on a bond contract. That doesn’t mean that the investor won’t get paid at all. In almost all cases, sovereigns restructure their debts by exchanging the old bonds with new bond contracts that must be agreed by a qualified majority of bondholders.

Sovereigns agree to restructure because remaining in default would imply remaining in financial autarky1, which has proven to negatively affect the economic growth and prosperity of a country. Sovereigns often restructure pre-emptively to avoid a hard default to improve their chances of regaining market access in the short term. The new bond contracts tend to have less favorable financial terms for creditors and usually have at least one or potentially all three of the following features: longer maturity, lower coupons, and lower principal.

Restructuring, a default by another name

A restructuring where maturities are extended but the principal and coupons remain the same is referred to as a reprofiling. Politicians often believe that reprofiling is not a default, but this is wrong.

Money has a time value because we all prefer a certain amount of money today to the same amount in the future. Investors incur a loss if they’re paid the same amount later than originally scheduled because the price of the new bonds will be lower than that of the old bonds.

Much feared haircuts are only one element in determining the recovery value

A reduction of the principal repayment is referred to as a haircut, but (100 - haircut) is not the same as the recovery value.

Let’s look at Belize as an example, which has agreed to repurchase its outstanding bonds at 55 cents on the dollar, but that is not a 45% haircut (as some media reports have stated). A 45% principal haircut would imply that Belize repays USD ~249 million to bondholders between 2030 and 2034 when the original bond was meant to mature – in addition to quarterly interest payments. If we assume an exit yield (or discount rate) of 12% given Belize’s reluctance to undertake a credible macroeconomic adjustment, then the recovery value of such a hypothetical restructuring would be just 34 cents on the dollar. In contrast, the recovery value of this repurchase agreement is marginally lower than 55 cents on the dollar as bondholders received an immediate payment equivalent to 55% of the principal including past due interest.

We welcome Belize’s ESG friendly restructuring. Belize obtained financing for the repurchase of its bonds via a Blue Bond issuance sponsored by The Nature Conservancy, as the country has pledged to invest USD 23 million in a marine conservation trust that would help to preserve one of the largest barrier reefs in the world. As bondholders, we supported this creative and ESG friendly restructuring.

Rejoice, most Covid-related defaults are probably behind us

Sovereigns typically default and restructure their debts at the onset of a crisis because this allows to shift resources they would have otherwise used for short-term-debt servicing to tackle basic needs. This allows them to recover faster from the crisis and in a less painful way for their population, i.e., enduring less severe budget cuts. We are now at an advanced stage of the economic recovery in most countries following last year’s economic shock brought about on by the pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns. Therefore, we believe that most Covid-related defaults are now behind us. We will publish a detailed article on this topic, sharing our outlook for six further markets which were thought likely to default.

Sovereigns rarely postpone restructuring until it’s inevitable

It would be irrational for a government to continue servicing their debts through a crisis unless they are fairly confident they can ultimately avoid default without causing excessive suffering to their voters. But sometimes, governments can be overly confident of their ability of being able to endure a crisis without defaulting. This was arguably the case of Venezuela, which unnecessarily postponed its default by at least two years until November 2017 – their economic depression started in 2014 – while forcing severe cuts in imports and private and public consumption. By then, the country was subject to US financial sanctions, which reduced the benefits of continuing to service the external debt.

Historically, the average recovery value has been around 53 cents on the dollar

Recovery values can vary significantly depending on the economic prospects of the sovereign and on their government’s willingness to negotiate in good faith. Bondholders recovered about 80 cents on the dollar from Ukraine’s 2015 debt restructuring and on top of that they received a GDP warrant. High recoveries like these or those expected for Zambia and Suriname contrast with relatively low ones mentioned above for countries with weak economic prospects like Argentina, Belize, and Lebanon.

In Sri Lanka’s case, the recovery value could be close to the historical average if the political situation is resolved quickly and the government reaches an agreement on an IMF program relatively quickly, as they have said they intent to do. But the recovery could be more in line with current bond prices (low 40s) if the political situation is not resolved quickly and the economy continues to be neglected.

Investing in distressed debt can be highly profitable, even if recoveries are below 100%

While the average recovery value is only slightly above 50% and not often above 80%, investors can reap high double-digit annualized returns when investing in distressed debt. This may sound counterintuitive, but the fact is that unconstrained EM bond investors almost never pay the full price for bonds that are likely to be restructured. On the contrary, they can often buy them at deep discounts.

Unconstrained and distressed investors benefit from forced-selling

Many investors are constrained as to what they can hold in their portfolios, for example, many cannot hold CCC-rated and defaulted bonds. A academic paper published by the IMF went through all EM sovereign distress situation of the 20 years preceding the Covid crisis and shows that a hypothetical distressed-bond investor that would have bought all EM sovereign bonds when spreads increased above 1,000 bps or when downgraded to CCC – a possible hedge fund strategy – would have made annualized excess returns of 17.2% (above the risk-free rate) over the 20 years preceding the Covid crisis. In contrast, constrained investors who are forced to sell bonds at the onset of a crisis – when downgraded to CCC or when spreads widen above 1,000 bps, hence reflecting a high implied probability of default – would have lost 1.75% (annualized below the risk-free rate) on this distressed part of their hypothetical portfolio. Meanwhile unconstrained investors, defined in the paper as buy-and-hold investors who do not sell bonds when a crisis begins, would have realized excess returns of 3.3%.

| Type of investor | Excess return (annualized) |

|---|---|

| Unconstrained | 3.26% |

| Constrained | -1.75% |

| Distressed | 17.22% |

Past performance not a guarantee of future results. Source: Andritzky and Schumacher (2019): Long-Term Returns in Distressed Sovereign Bond Markets: How Did Investors Fare?

In rare occasions recoveries can be extremely low

While the average historical recovery value is 53 cents on the dollar, there are also examples of very low recoveries. Probably the worst negative example is that of Cuba, which defaulted on its debts in 1986 and only reached a restructuring agreement with the Paris Club of bilateral creditors in 2015 on the back of the Obama-era rapprochement policy. Yet Cuba has failed to meet these new commitments and re-scheduled repayments once again. Moreover, the island-nation has not restructured its debts to the London Club of private creditors, who have delivered a few proposals since 2015. Thus, for private creditors the recovery has been zero so far.

These situations are extremely rare because governments usually have incentives to resolve their defaults quickly to be able to regain access to international capital markets and to avoid unnecessarily costly litigation processes and potential asset seizures. Venezuela is the only other clear example in which a sovereign defaulted years ago (in 2017) and is not expected to restructure in the short term because US financial sanctions prohibit a bond exchange.

Case study Russia: Possibly a rare example of an unresolved sovereign default due to sanctions.

In our recent article: Three Ukraine-Russia scenarios and bond recovery values for Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus , we explained that US sanctions are likely to force Russia into a sovereign default in the short term and that the prospects for recovery may be very low because sanctions on the finance ministry would prevent the country for restructuring its debts. Like in Venezuela’s case, investors may have to wait until the US provides sanction relief to allow a restructuring, which may take years.

Unlike Venezuela, Russia’s remains financially sound even after the seizure of half of its international reserves. Russia’s indebtedness is very low, and it remains a twin surplus country able to generate large amounts of foreign currency revenue. In other words, were it not for sanctions preventing bondholders from receiving payments a default would not be necessary. An alternative solution would be for the sovereign to appoint a non-sanctioned domestic financial entity to repurchase Russia’s sovereign bonds at deep discounts.

Case study Sri Lanka: Cruising on autopilot to default

The government clearly overestimated its ability to muddle through the covid crisis. Sri Lanka’s bonds have been trading at deep discounts since the beginning of the pandemic, but the government has repeatedly stated they will avoid default. Gross external financing needs are considerable in the short-term and FX reserves have been dwindling and are now at worrisomely low levels. Since last year, we have been expecting Sri Lanka to default before its July 2022 bond maturity.

Sri Lanka is a highly indebted nation whose main source of FX revenues are remittances and tourism. Tourism arrivals dropped to zero since the beginning of the pandemic and only started to recover more meaningfully in the last six month. It had recovered by to around 44% of its pre-Covid level in March 2022 despite a significant decline in arrivals from Russia. Moreover, the ongoing protests are likely to discourage holidaymakers from visiting Sri Lanka.

Remittances performed well in 2020 but started to decline after the central bank pegged the currency at 200 rupees per US dollar, which created a weaker parallel exchange rate and disincentivized formal remittances. Remittances were down by more than 60% year on year in the first two months of 2022. Losing its two main sources of FX revenues, while simultaneously pegging the exchange rate for almost a year (it has been liberalized recently) and continuing to service its external debt resulted in a predictable decline of the central bank international reserves from USD 7.9 billion in February 2020 to just 2.3 billion in February 2022.

Active investment is key to unlocking returns from distressed debt

Investing in distressed debt, need not be a distressing experience. As we have shown, investors often overreact to initial news of defaults or restructurings and forced sellers can even exacerbate the situation, thus providing active investors with a window of opportunity.

For a portfolio to profit from distressed requires a thorough understanding of the underlying issuer and a high conviction from the investor that the recovery value will be significantly above the prevailing market prices.

Important Information

Fixed income securities are subject to certain risks including, but not limited to: interest rate, credit, prepayment, call and extension. International investing involves special risks including, but not limited to currency fluctuations, illiquidity, and volatility. These risks can be heightened for investments in emerging markets. Diversification does not assure a profit or protect against possible losses.

1. Financial independence, i.e. without access to international financial markets