Why inflation risks are still tilted to the upside

TwentyFour

With inflation running at 40-year highs in many parts of the world, it is easy to get carried away with making comparisons to the dark economic days of the early 1980s.

We know supply side shocks have contributed significantly to today’s inflation levels and in the fullness of time these will improve, and we also know that central banks have finally woken-up to the growing inflation threat and have changed their stance emphatically. Given many of the secular drivers of lower inflation over the last decade are also likely to be present in the coming decade, it is easy to see how these facts would naturally lead to expectations of lower inflation levels in the future.

Why then are we still worried that inflation risks are tilted to the upside? While we certainly expect inflation will retreat later this year, it is the level it ultimately retreats to that we think may still surprise to the upside. This is very important for asset valuations, especially as much of it is supply side related and central banks feel they have little control over this.

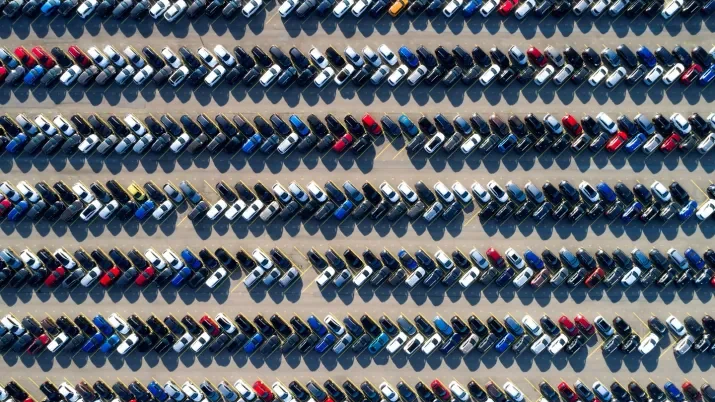

If we look at the current drivers of inflation, it is clear to us that some are likely to leave a mark more permanent than central bankers are currently projecting. Let’s start with COVID-19 and its supply side shocks. The world’s supply chains, which were running rather efficiently in early 2020, were stopped dead by the pandemic and trade in many sectors all but ceased for several months. What followed was a gradual – and uneven – reopening of trade around the world, followed of course by equally uneven re-closures. To assume that the world would suddenly reopen and trade would flow as efficiently as before was more hope than reality. Global trade will take several years to run as efficiently as it did pre-pandemic and companies will seek to hedge their supply chain risks. This will mean companies having a more diverse source of suppliers, and not necessarily choosing the most cost-efficient solution. You could almost categorise this as a disaster recovery plan for supply chain shocks, and we know this type of expense is a permanent additional cost. Some companies will have reacted quite quickly, some may just be doing this now and some will only react in the future, so this is a live and ongoing source of new inflation.

The demand surge that followed the reopening of global economies exacerbated the supply shock, and we have to question whether this has had any permanent impact on consumer and business behaviour. Certainly the enormous liquidity injections from central banks created pockets of uncomfortable valuations in all sorts of assets. However, one would think that a reversion towards more normal policies would reign a lot of this in. The central banks are certainly alive to this now.

Then of course we have the war in Ukraine which has added significantly to the commodity price shock that was already building before the Russian invasion. With soaring commodity input prices, the second order effects are going to be incredibly widespread. Statistically they might be temporary (or ‘transitory’) but the second order effects will take time to filter through. Businesses will also be seriously evaluating counterpart and country risk when it comes to entering into long term contracts for commodity provision.

This brings us nicely on to the last topic which is ESG. This was always going to be a driver of inflation because there is a cost to doing good, and again the war in Ukraine has made this a much more urgent and important topic. Country risk is now first and foremost in investor concerns. We have rapidly seen what excluding Russia can do to commodity prices, and those businesses and economies that were overly reliant on one source of delivery are facing some very difficult decisions. Diversifying country risk will have a similar effect to the supply chain issues mentioned above, with businesses and economies not necessarily selecting the lowest cost option.

Here we need to touch on China, which for many investors and businesses might be a country that feels uncomfortable to invest in or partner with given what has happened with Russia. Given the hugely important role that China has played in keeping producer costs lower over the last few decades, any significant move away from Chinese production is likely to have the opposite effect. While it is not a base case for there to be a such a move, at the margin we think some businesses will be seeking to diversify some of this risk. In the world of fund management the industry is currently torn on whether to exclude Chinese country risk from sustainable labelled funds, and it certainly feels like pressure is building on this front.

Overall then there are a few reasons why longer term inflation may be a little higher than in the previous economic cycle. Central banks can tighten policy to deal with the demand side of the equation, but some of these supply related issues do look set to linger for longer. So the move higher across risk-free yield curves is justified in our opinion, at the front end because rates will be going up rapidly and at the long end because inflation expectations are simply not as anchored as previously.

From a fixed income standpoint the move higher in risk-free yields is certainly welcome, as at some point in this cycle investors are going to need to rebalance portfolios with more rates-sensitive bonds, and doing so at higher yields is of course a benefit. That point in time is getting nearer as we mentioned last week, as we are soon to be heading into late cycle territory where global economies have much less of a buffer to sustain future shocks and investors’ risk-off product of choice will as usual be US Treasuries. Timing of course is very important and trading US Treasuries is notoriously difficult for short term investors, hence we prefer to think of our own allocations in a pro-cyclical manner.