European Equities: The Road to Revitalization

Quality Growth Boutique

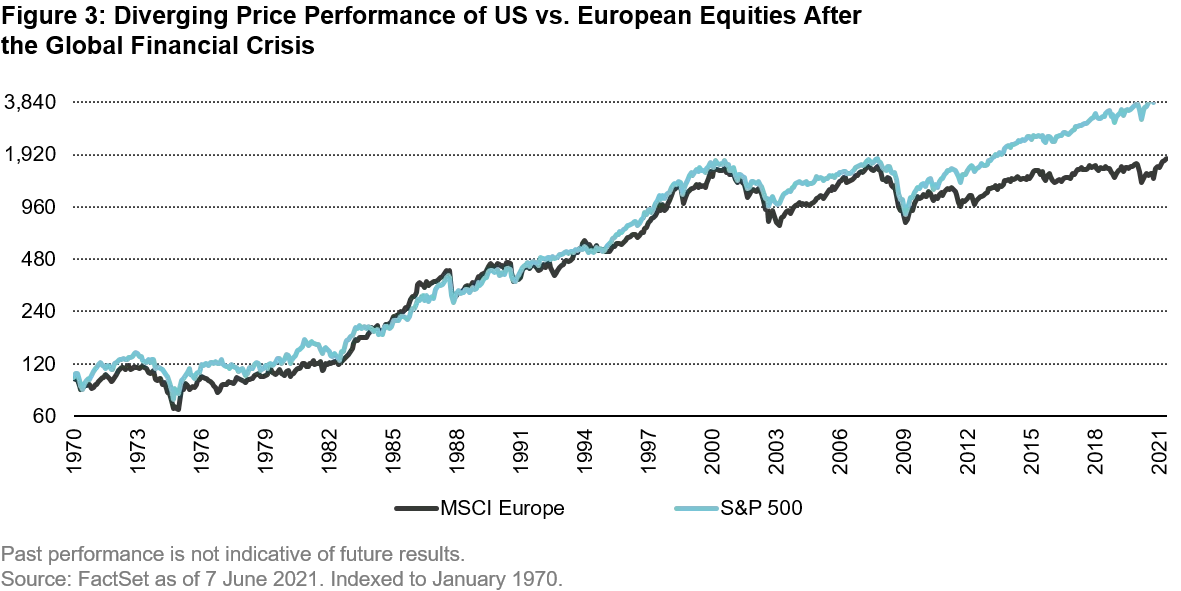

European equities have lagged the US significantly since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). However, this has not always been the case. Europe and the US performed in line for many years leading up to the GFC. After at least four decades of growing at a similar pace, what had changed? And is there any reason to believe that this scenario can reverse?

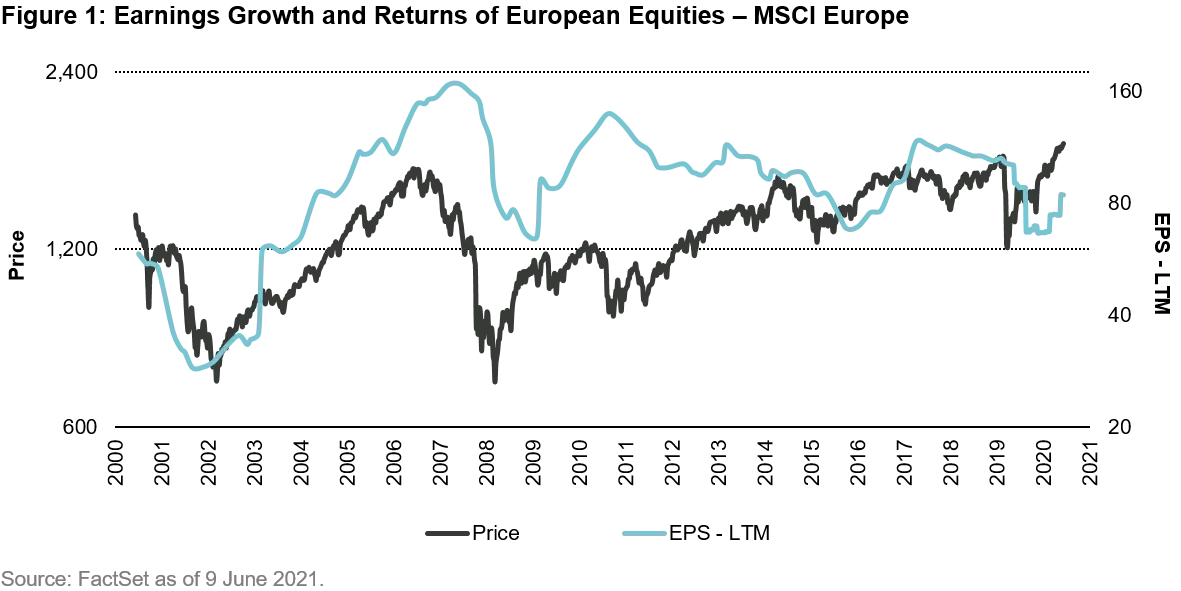

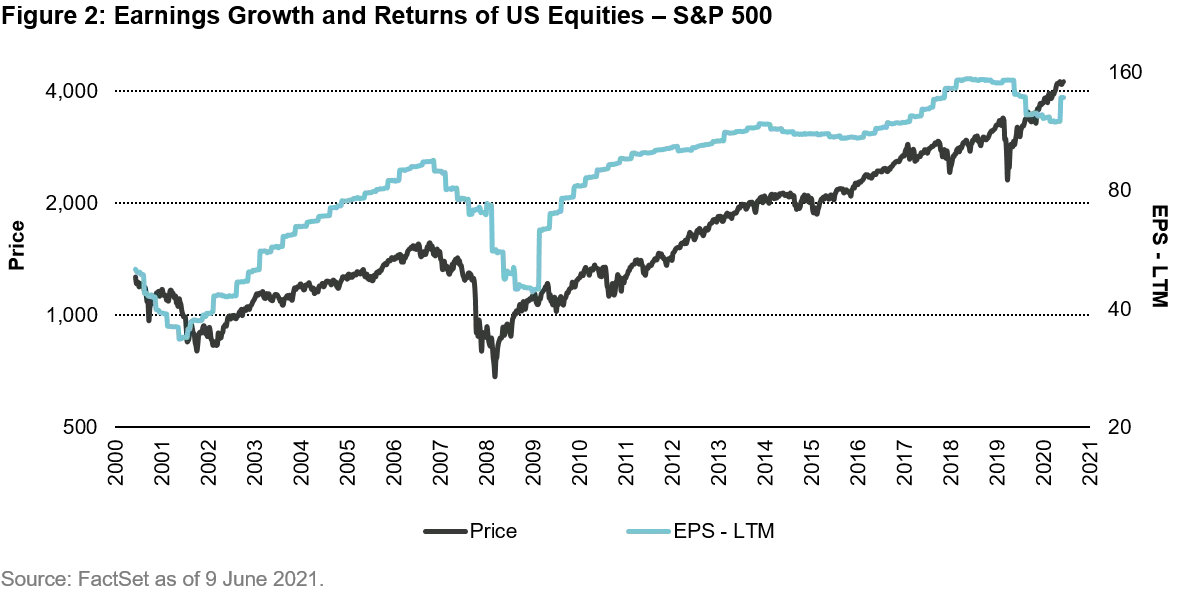

There are many reasons that support an improvement in Europe’s relative performance going forward. From the GFC through the end of 2019 (pre-pandemic), Europe’s underperformance was driven overwhelmingly by lower earnings growth, as earnings in the MSCI Europe Index declined 22.5%, while they rose 58.8% for the S&P 500. This largely explains the relative underperformance, although valuations also played a role, with multiples for the S&P 500 increasing only slightly more than they did in Europe at 32% vs 25%, while also starting from a higher base.

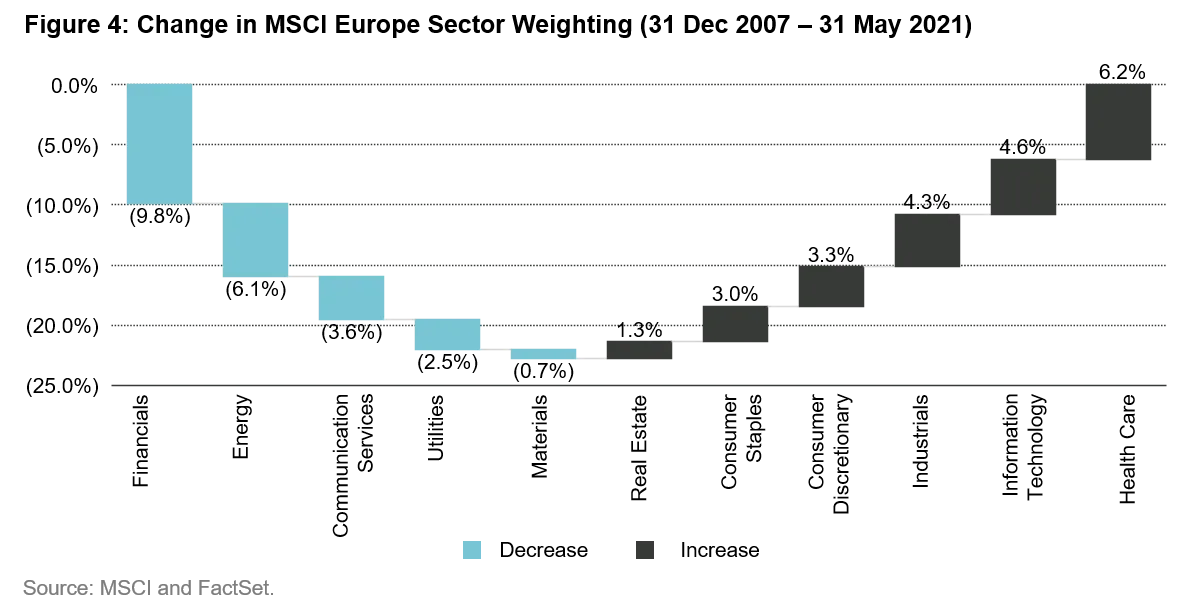

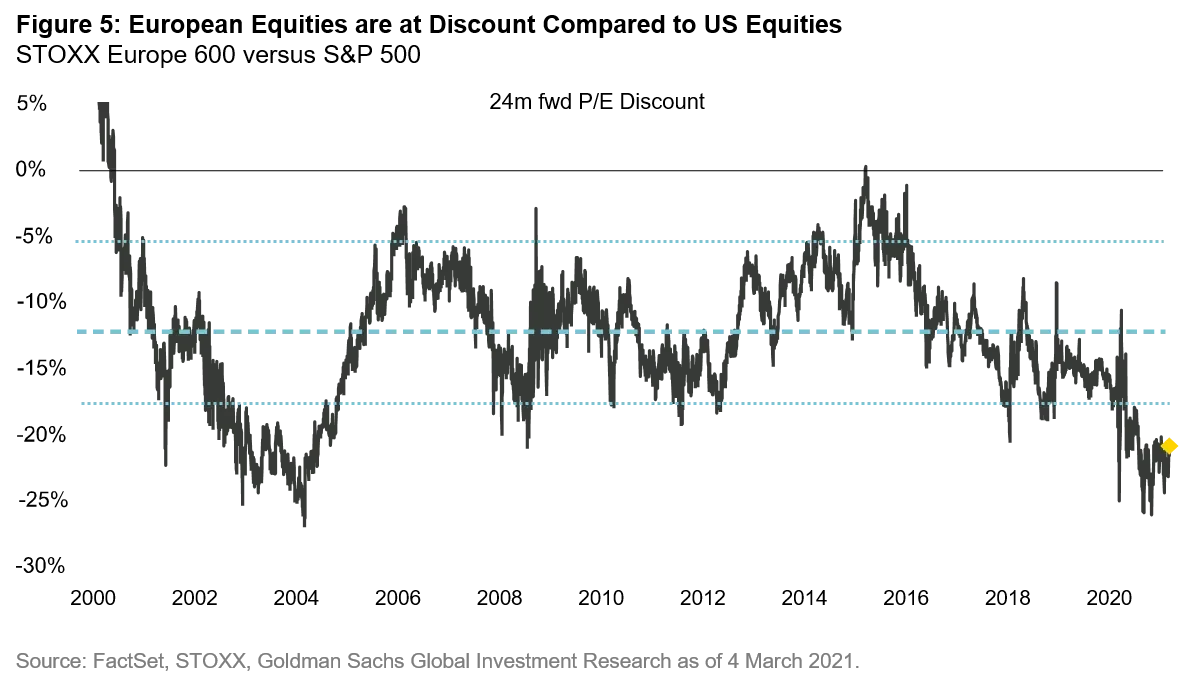

In this paper, we argue that future earnings growth in Europe should improve. The Index looks markedly different today than it did before the GFC, with less reliance on banks, energy and materials, and greater exposure to higher and more consistent growers in technology and health care. As higher quality businesses and faster earnings growth are recognized by investors, the current valuation discount versus US equities should shrink. Further, macro reforms and a leading position in ESG (which should increasingly be reflected in stock prices), will likely result in better performance and valuation for European companies.

What does Europe’s past tell us about the present?

Over the past 20 years, investing in benchmark European equities (MSCI Europe) has not been lucrative. It has weighed on both Global equities (MSCI ACWI), where Europe is 17.5% of the Index, and International equities (MSCI ACWI ex US), where Europe is 41.5% of the Index. This underperformance wasn’t based on a high starting price – aggregate earnings are lower today than they were in 2004.

It is interesting to note that up until the GFC, Europe and the US performed in line for a very long period of time.

After at least 40 years of growing at a similar pace, what had changed? And is there any reason to believe that this scenario can reverse?

Pope Francis, not known as an avid investor, summarized the thoughts of many asset allocators during his 2014 speech to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France. “In many quarters we encounter a general impression of weariness and aging, of a Europe which is now a ‘grandmother’, no longer fertile and vibrant. As a result, the great ideas which once inspired Europe seem to have lost their attraction, only to be replaced by the bureaucratic technicalities of its institutions.”

Looking to the past can help us understand where we are today. The evolution of Europe and the single market idea has provided investment opportunities in strong local companies with quality franchises and global aspirations. Since the original European Economic Community founded in 1957, the expansion into the European Union in 1993, and the launch of the euro in 1999, equity investors benefited from access to a more open, unified, large and developed consumer market. Compelling investments emerged as historic conglomerates refocused, leading brands grew in scale, and the longer-term move towards a single economic market drove growth. But any economic regime is only strong if it can be truly tested.

The GFC of 2008-2009 created a political limbo in the core Eurozone countries, with ongoing turmoil as various bank balance sheet and credit issues morphed into sovereign debt crises across swaths of the Eurozone and EU. Macro fears overtook investment rationale. Unlike in the US, where proactive monetary and fiscal policy combined to support liquidity and shore up the financial system (especially banks’ capital with TARP support and equity issues), in Europe the ECB stood alone with Mario Draghi promising that the institution ‘will do whatever it takes’ to keep the EU and financial markets from entering a downward spiral. Furthermore, political fracturing of Southern and Northern EU states weakened confidence in resolving the crisis or reaching a common fiscal approach.

The economic toll from self-imposed fiscal austerity in the EU was harsh. The decade of 2010-2020 saw stubbornly high unemployment levels, especially hitting the youth segment, and feeble domestic economic growth. The pent-up political backlash and rise of populist parties and agendas added to the macro overhang, culminating in the Brexit saga, and withdrawal of the UK from the EU in December 2019 (47 years after joining).

But the post GFC decade that ended in Brexit also may be sowing the seeds for a better tomorrow. The UK’s withdrawal led to some serious political soul-searching more than 60 years into the EC/EU evolution, spurring a key macro review for new ideas to reboot EU confidence.

The road to revitalization

The COVID crisis brought a humanitarian and economic hit to the region, but it also accelerated this newfound era for revitalization. This time the EU recognized the need for strong combined fiscal and monetary action. The last 12 months have seen the birth of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) fund. This is the first ever pan-EU bond-funded recovery and investment spending response to a crisis. The NGEU is sized at €750 billion and has a targeted €1.8 trillion project spend, equivalent to roughly 12% of EU GDP. This much need program is both ambitious and novel for the EU. Its goal is to reinvigorate industries, drive investment into new technology and renewable energy sectors, and provide a vote of confidence into the domestic EU heartland.

More important than just giving a boost in response to the current downturn, the NGEU, in combination with other reforms implemented during and in the wake of the GFC and Eurozone debt crisis (establishment of the European Stability Mechanism, European Systemic Risk Board, bank stress tests, higher capital ratios), should make future crises less existential. While not the United States of Europe, it is one step closer, which should lead to a faster response when another crisis arrives.

The change in mix of businesses in Europe is another positive development. At the time of the GFC, the European benchmark looked significantly different than the US one. And while that didn’t matter prior to the GFC, it did lead to very different returns afterwards. The US was simply more exposed to growth and technology, while Europe had a heavier weight to banks and value sectors. The past decade plus has been good for the first group and poor for the latter. European banks for example, had a large weighting in the index at the time of the GFC. Those companies have faced fines upon fines, increased regulatory burdens, lack of loan growth, weak balance sheets, and negative rates. It is no wonder financials – and Europe – underperformed.

We are currently in the midst of a value rally. Indeed, the outperformance of value stocks is similar to the value bounce we saw in the US after the GFC as the local economy and markets recovered. As confidence returns and politically extreme outcomes calm, the “peace” dividend should power a wide swath of businesses across Europe; if the US is a guide, the post GFC decade was strong for growth stocks. Europe does not need a long value rally to improve its relative performance.

Earnings should improve

The MSCI Europe Index looks substantially different today than it did during the GFC. This is a result of years of value underperformance shrinking the weight of value stocks, combined with new companies entering the European markets in more dynamic spaces. Examples include Netherlands-based fintech company Adyen and global consumer internet group Prosus, along with many others.

While Europe still lags the US in tech exposure, it now has over 8% in tech versus only 3.5% before the GFC (31 Dec 2007). At that point too, Europe had a 13.75% exposure to banks, 3.5% more than the global benchmark, while today Europe is down to 7.51% in banks, less than 40 basis points more than the world average. We see other changes as well, such as a significantly lowered exposure to the volatile energy and financials sectors, and low growth utilities. In addition to fast growth technology, Europe has a greater exposure than it did to higher quality consumers staples and discretionary, health care and industrials. In general, we believe Europe has more exposure now to faster growing, higher quality businesses and is more balanced than in the past.

Valuations are relatively attractive

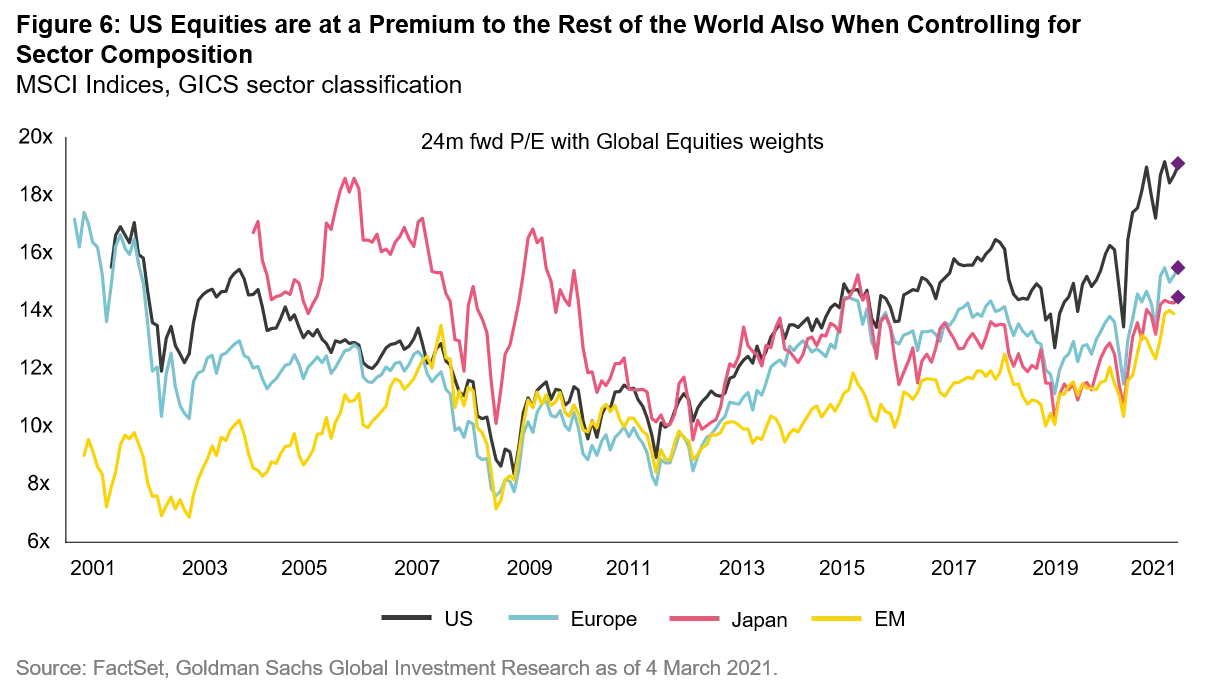

Furthermore, after a decade of underperformance, we believe valuations in Europe are more attractive than those found in the US. And this is true, even after adjusting for sector exposure, meaning the better valuation is not a function of the US having higher valuations because it has more technology companies and fewer banks.

Can European equities really outperform the US?

The US is firing on all cylinders on COVID recovery, massive stimulus, and spending. Europe, with its recovery fund and negative rates, seems downright restrained. Near term, this should lead to a hotter running US economy. But US spending should help European companies, as many are levered to global growth. It is also important to keep in mind that this won’t last forever. Politics in the US do not go in a straight line and there are already concerns around debt-to-GDP being higher than in the aftermath of World War II, its previous historical high. Tax reform, including increased corporate taxes, is on the horizon. Near-term spending on COVID recovery and infrastructure may be as good as it gets. The US will not be as free spending in the future; there will be a retreat, and the rest of the world will look relatively more attractive.

What if inflation increases?

Low inflation, which has been a drag on many European companies since the GFC, may finally be coming to an end. This has not just hurt commodity producers, but also a wide array of European businesses. Europe has many great brands, with long histories, that have pricing power as costs increase. These regular price increases have been lacking since the GFC, so for those that can pass rising costs along to the consumer, and even add a little, a return of inflation would be positive for business. The buyer of a Ferrari won’t care if the price is up a few percent, nor will the purchaser of a Nespresso pod. A world without a Japanese style stagflation should be good for Europe

The benchmark has changed, inflation is okay, there have been reforms – but will earnings grow?

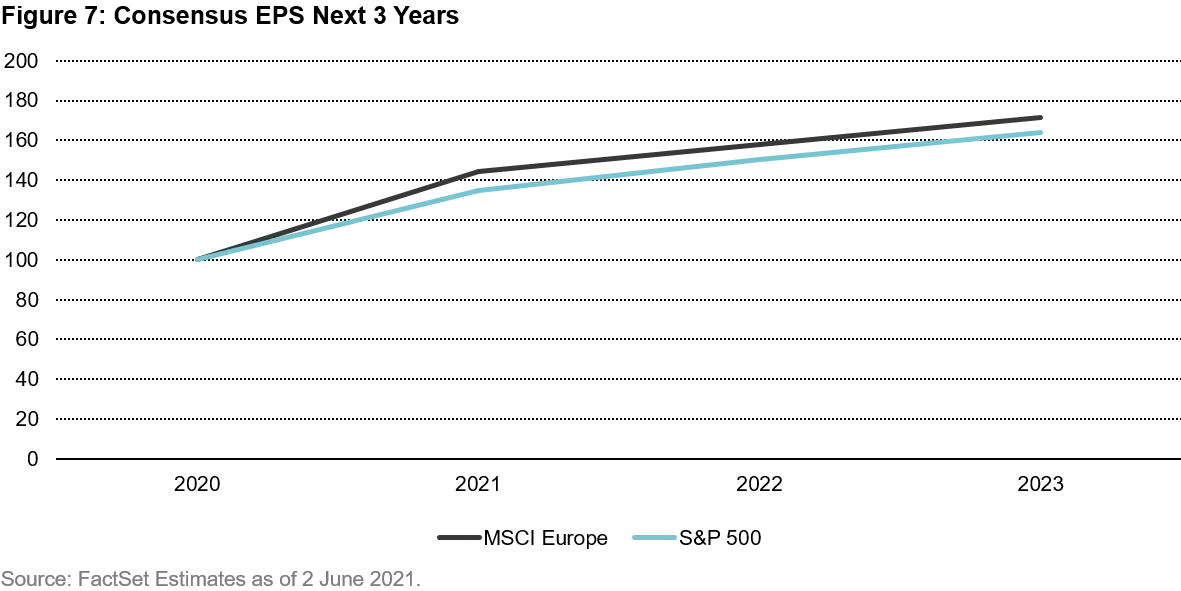

Figures 1 and 2 illustrated that since the GFC earnings in Europe paled in comparison to the US, a time period that correlates to European equity underperformance. We’ve argued in this paper that the European benchmark has improved, and Europe shouldn’t be a laggard going forward. To really see that though, you need to see earnings growth in Europe improving. Interestingly, that is what earnings expectations show.

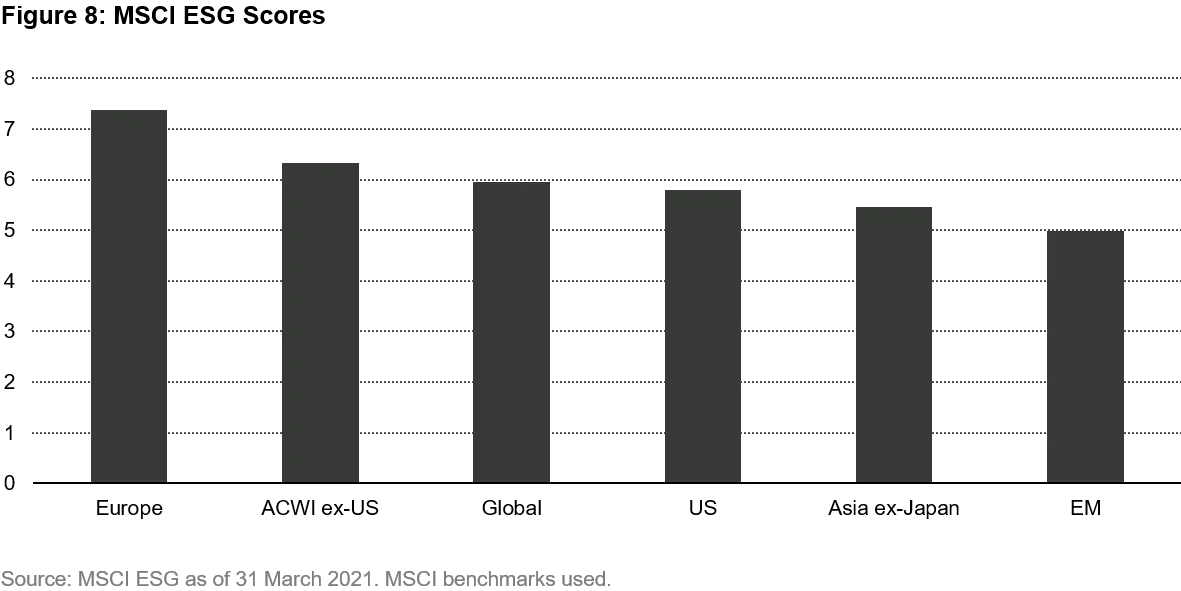

Europe is leading the way in ESG

Europe’s progress on ESG has become clear as indicated by third-party ratings and investors in different geographies. This is important as companies that have not yet determined how they will address issues beyond pure financials will eventually have to increase investment and business processes. Furthermore, as investors in other regions begin to consider more than just financial metrics, ESG scores will increasingly be reflected in valuations. Going back to Europe’s more attractive valuation versus the US (Figures 5 and 6), it is important to note that US earnings forecasts do not yet include the costs of adjusting to lower carbon emissions. The US only reentered the Paris Agreement on February 19, 2021. To reach its goals, major change is required; it is not business as usual. Including those costs would potentially mean an even more favorable valuation for European equities.

A clear case for a European equity allocation

Not everything is perfect in Europe. But it isn’t elsewhere either. Issues that have negatively weighed on Europe over the past decade we expect to be smaller going forward. We believe the index has faster growing and higher quality companies, and the market trades on a relatively attractive valuation. Europe is somewhat of a contrarian bet if investors look back at the past dozen years and extrapolate that the future will look like the immediate past – in other words, a one way bet on the US. The longer-term history, the fundamental changes that have occurred in Europe over the more recent past, and an increasing investor appetite for more ESG factors signal that investors overlook Europe to their own financial detriment.

1. 31 Dec 2007 to 31 Dec 2019, Source: FactSet

Certain information ©2021 MSCI ESG Research LLC. This report contains “Information” sourced from MSCI ESG Research LLC, or its affiliates or information providers (the “ESG Parties”). The Information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced or redisseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or a component of any financial instruments or products or indices. Although they obtain information from sources they consider reliable, none of the ESG Parties warrants or guarantees the originality, accuracy and/or completeness, of any data herein and expressly disclaim all express or implied warranties, including those of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such, nor should it be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance, analysis, forecast or prediction. None of the ESG Parties shall have any liability for any errors or omissions in connection with any data herein, or any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages