ESG – Modern slavery: a python in the plumbing

Quality Growth Boutique

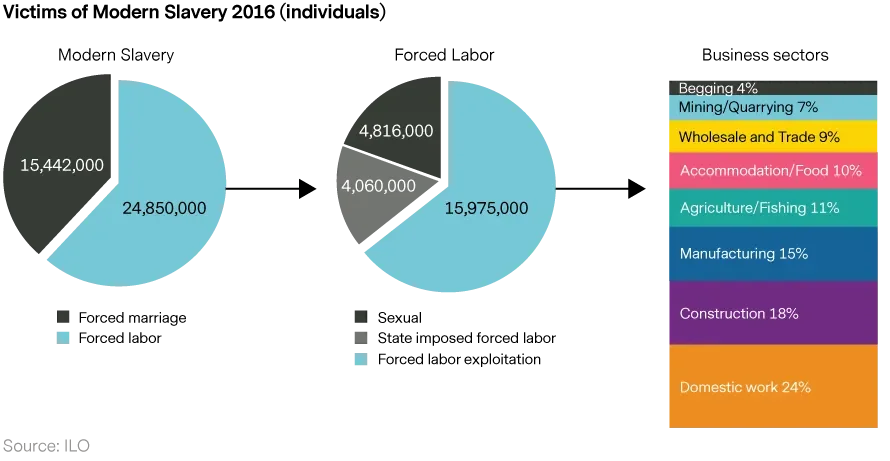

It’s a reflection on the twisted end of human society, that in the 21st century, 25 million people live as forced laborers. This was the 2016 estimate by the International Labour Organization (ILO1), a UN agency. On its figures, some 89 million people were trapped in modern slavery at some point during the five years to 2016 – that’s more than the population of Germany. This sickening greed is not walled inside poverty-wracked geographies. In fact, part of the reason it's large is found in many of our own homes.

The reason for slavery has not changed – it has always been about money and power. But since 1865, when slavery was banned in the United States, the methods have evolved as laws and opportunities changed. The chains of modern slavery are coercion and lies – as well as force. Modern slavery is an umbrella term for labor trafficking, sex trafficking and forced marriage. It generated an estimated $150 billion of profits in 20122. For context, this was similar to the entire net profit of the S&P 500 financials sector that year.

Profits from forced labor creep into our homes through imported goods, enabled by the complex subcontracting and global supply chains, where agents find better prices. Food ingredients are grown, picked, fished or raised by the unpaid; clothes are made in sweatshops from cotton picked by forced labor. Many components in the things we buy have the potential to be made by trapped humans. Big profits from forced labor is labor arbitrage past its breaking point. Products from low income countries, shipped to customers in wealthy countries, at bargain prices.

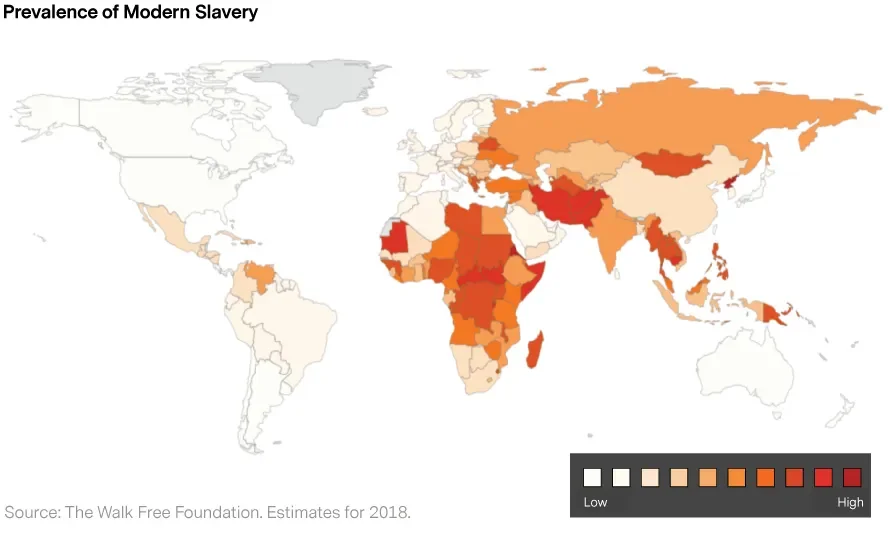

By number, most victims are in Asia Pacific, accounting for two thirds of ILO’s 2016 estimate, followed by Africa (14%) and Europe/Central Asia. However, the profits from forced labor follow wealth, with 47% coming from the developed markets including the EU, and 32% from Asia Pacific2.

What is modern slavery?

It’s defined as “all work or services that is extracted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. The methods have changed considerably since 1865 when the US Thirteenth Amendment3 banned slavery. These days, rarely are victims of modern slavery the ‘property’ of anyone. Methods of entrapment include: working to pay off debt on impossible-to-repay terms (debt bondage), withheld wages, threats of violence to the victim or relatives, threats of legal action, or withholding passports and other documents. The ILO estimates 51% of victims are held through debt bondage.

Where are the victims?

Of the 25 million people estimated to be in forced labor, 16 million are exploited for labor by the private market, 5 million for sex, and 4 million by state actors. Sexual exploitation accounted for around two-thirds of the profits. However, 64% of the victims by number are laborers – generally in low-skilled manual work. Nearly a quarter of private sector forced laborers are domestic workers. The sectors where forced labor is more often found include: construction, manufacturing, agriculture and commercial fishing. By product, the Walk Free Foundation has identified a list of imported products at risk of having used forced labor which includes laptops, computers and mobile phones, as well as garments, fish, cocoa, sugarcane and cotton.

Supply chains

Today’s company supply chains are so complex because they include multiple tiers of suppliers, i.e., the company buys from suppliers (first tier), who buy goods or services from their suppliers (second tier) and so on. Problems tend to get worse with further removed tiers. This was illustrated in a study by Sedex4, a non-profit organization focused on supply chain transparency. In 2013 it ran a study of 10 companies with 3,922 supplier relationships and 6,775 audits. The study revealed that the companies engaged with 45% of their tier one suppliers, 47% of tier two suppliers, but only 7% of tier three. It also found that average instances of non-compliance per site audit for Tier 3 suppliers was 27% above those for Tier 1 suppliers.

Governments can’t do it alone

Getting laws in place is one thing, but governments cannot be effective without insights from companies or third-party investigators on supply chain risks. In 2019, Reuters reported that US customs had blocked certain imports suspected of involving slave labor. They included clothes (from Xinjian, China), rubber gloves (Malaysia), gold (DR Congo), and diamonds (Zimbabwe). But the value of goods blocked by the U.S. since they were banned in 2016 was stunningly low at just $6.3m5.

While most countries banned slavery long ago, many have no laws or policies banning imported goods involving forced labor. The list includes a number of G20 countries – including Canada. Laws covering slavery in the supply chain include: UK (Modern Slavery Act – MSA - 2015), France (Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law, 2017), the US (Section 307 of US Tariff Act), Australia (MSA, 2018), and the Netherlands (Child Labor Due Diligence Law, approved 2019, not enacted).

Active owners have a role

Forced labor is a big and diverse problem and we see no one magic agency or group that can break this enterprise alone. It can only be driven back by a partnership of interested parties. Active investors who communicate regularly with company executives can contribute to the effort. It may seem like a small contribution, but engaging at the right time, with the right people can bring leverage by taking red flag issues direct to decision makers in some of the largest companies on the planet.

But recognizing and understanding a red flag can involve detailed investigative work. For this you need the right skill set. It means dealing with people, not numbers. Think journalists, not mathematicians.

When looking at controversial issues, unsurprisingly we find there tends to be a higher number of reported issues related to employees of companies, rather than employees of suppliers. The low incidence in the supply chain largely reflects the lack of knowledge and visibility about what goes on within parts of the supply chain, as well as the lack of visibility of which factories are supplying which company.

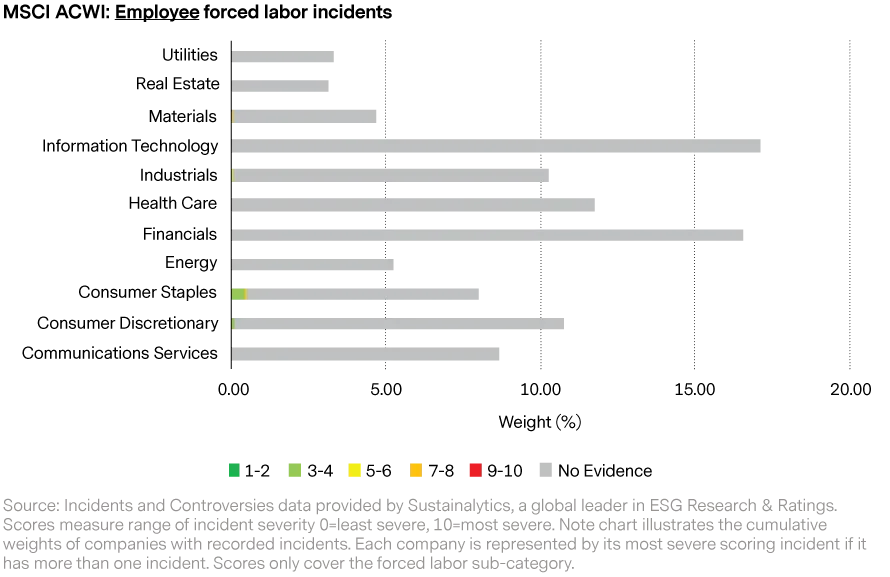

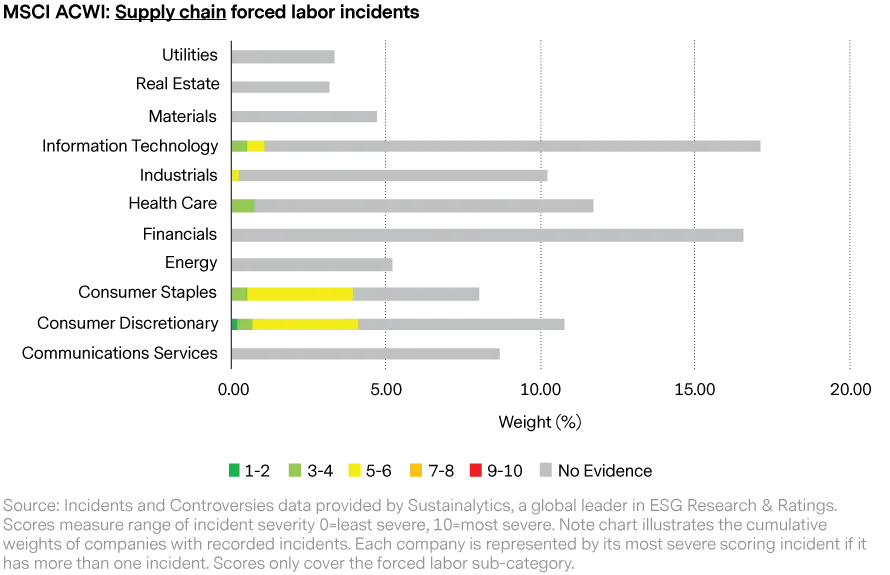

The charts below outline forced labor incidents. While there are almost none for company employees, there are some moderately serious issues from some suppliers, notably within consumer sectors.

Examples of recent moderately serious labor issues within the supply chains of larger MSCI ACWI companies include:

Procter & Gamble (US): in 2018 a palm oil supplier, FGV Holdings Berhad, had its Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) sustainability certificate suspended on certain assets due to the failure to supervise contractors that may have been involved in forced labor.

Samsung Electronics (South Korea): admitted to having subjected workers to excessive overtime following a report from New York based NGO China Labor Watch (CLW). The report accused Samsung of forcing its workers to well over 100 hours of overtime work per month, unpaid work, making them stand for 11 to 12 hours while working, as well as a number of other issues at its China-based plants. Samsung Electronics admitted it found illegal work practices in an audit of 105 of its Chinese suppliers.

Associated British Foods (ABF): is the owner of the Twinings Tea brand and the retailer Primark. In 2018, the India Committee of the Netherlands (a Dutch NGO), found that some of the suppliers to the company were holding workers in captivity and preventing them from leaving the factories. Additionally, in 2015, the BBC reported on the poor working conditions of tea workers supplying Twinings in Assam. They were found to be malnourished due to low wages. Twinings and Primark both now publish a list of all the factories they source from.

Partnership

Investors are in a position to help in a small way on the large goal of taking profits away from the slave trade. We would like to see more transparency from companies through disclosures of supplier lists, both by name and factory, maybe through a central repository so competitive advantages are not divulged. It is a key step that would provide visibility for consumers, NGOs and shareholders alike. Importantly, it would help reduce the incidence of innocent consumers supporting the profits of human traffickers.

Ultimately, the goal is to leave the business of forced labor slavery where it belongs – in the ugly chapters of history books.

Abraham Lincoln “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”

1 The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the UN agency for social injustice

2 ILO and Walk Free Foundation report - Global Estimates of Modern Slavery (2017)

3 The thirteenth amendment to the U.S. constitution ”Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

4 h

ttps://cdn.sedexglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Sedex-Transparency-Briefing.pdf

5 Thomson Reuters Foundation study