ESG: Can social and short-term investors co-exist?

Quality Growth Boutique

Social media has sped up the feedback mechanism from act to consequence. Get Social, ‘S’ from ESG, wrong and a company stands to lose customers and employee loyalty, gain the attention of regulators and damage the value of the business. We think there is little choice if a company is going to sustain – it needs to deliver Social while sacrificing little, if any, profitability. Companies able to progress their business models through investing profitably into their core stakeholders should command a premium valuation for a stronger franchise—one that is better able to sustain growth.

But can the short-term demands of shareholders coexist with long-term returns from enriching stakeholders, such as employees, customers and the local environment? Liquid markets in company shares allow rapid changes in ownership, which, along with cheap funding, encourages the takeover of companies not sweating their assets. And sweating the assets can push back incentives to invest across the business for returns that may take several years to metamorphose into earnings per share. Investment managers hold an important role behind management, as do the end investors.

Social responsibility was a big deal in the 1960s but faded. The context was different then. With socialist mood swings, profits started to be seen almost as an unethical offset to society’s wellbeing. This led to the famous 1970 New York Times Magazine1 article by Milton Friedman “The Social Responsibility Of Business Is To Increase Its Profits.” He rejected “social conscience” spending by managers as “pure and unadulterated socialism.” Not holding back, he wrote:

“…corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while confirming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.”

But cultural sense has evolved again with a new generation of savers. While blunt and linear in today’s context, Friedman’s view was not entirely wrong. A company will not survive, or deliver an important goal to savers, if it is not profitable. The change we see is that social responsibility and value maximization are not mutually exclusive.

How do you get there?

We see three important drivers to deliver the value add of social responsibility:

- belief in the value-add from long-term investments

- consistent direction from owners

- evidence it can be done

Belief - taking a step into the unknown takes conviction. Visibility on a new project might not be more than understanding the costs and a sense the revenue should arrive. If a manager has confidence that $100 invested in a 10-year project is worth $300 on the company’s market value today, the investment is likely to happen. If managers see the benefit of investing into software, machinery or humans as value drivers of productivity for the long run, that’s a start. If they recognize humans are the only ones able to make paradigm changes in production methods, product design, or customer service, that could be vital to staying in business – pathways to a stronger operation can be built. Management experience improves the visibility and chances of success for many long-term investments.

Consistent owners - a stable set of goals from the owners allows experience to accumulate. The less stable the priorities of the owners, the more likely management aims at the lowest common denominator: profit maximize near term…and try to keep it going. Here, the nature of companies listed on exchanges brings challenges.

The more liquid an investment, the easier and cheaper it is to buy or sell. But the yang of a liquid market’s ying is transient ownership. Transient ownership is part of the deal – underperforming assets get taken out, but so can solid and conservatively run businesses. We saw this with even keeled Unilever nearly succumbing to a hostile takeover by the cost cutting Kraft Heinz. Unless core investors remain with the company through tough times and withstand undervalued takeover bids at the cost of a short-term lift, solid growth companies will continue to get taken out and managements are less inclined to take the long-term investment risks. For investors to sustain over the long term, they need to partner with clients who understand their patient approach, and ideally match their investment horizon.

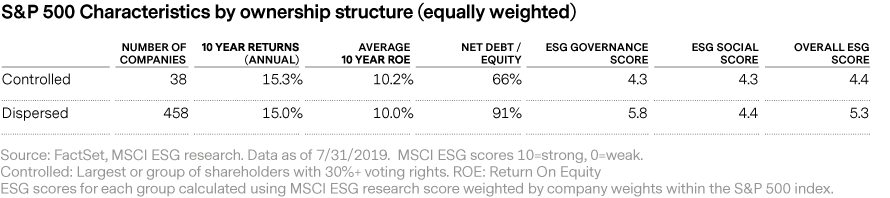

An alternative for owner stability is controlling shareholders – which can bring challenges for minority shareholders. Comparing S&P 500 companies with controlling shareholders (30%+ votes) against the rest, there is little difference over the past 10 years in stock returns or operating performance (return on equity). The controlled companies had lower leverage – which makes sense for owners with consolidated wealth. But the controlled companies as a group had lower ESG governance scores (from MSCI ESG), reflecting the challenges that can arise with stubborn controlling shareholders.

Evidence – Evidence of successful steps forward in management approach opens the eyes and makes a difference – the consulting industry was built on it. Most managers are not brilliant enough to crack the mold they grew up in. But evidence from visionary leaders can add value the same way a franchise can for a less original but able entrepreneur. We think of leaders in different markets – companies such as Starbucks (U.S.), Unilever (UK/Netherlands) and HDFC Bank (India) whose managers have delivered good products to their customers over many years, trained and treated their staff as partners, and set an example for the market. For example, at Unilever purpose driven brands (improving health, reducing environmental impact) have not just spurred sales but employees are excited to work on projects that are both profitable and deliver a social function.

Inspiration - the Story of Robert Owen

Arguably, the father of social-not-socialist capitalism was Robert Owen, a Welshman born in 1771. Owen demonstrated that it was possible to run a world leading business where well treated employees were highly productive and generate great returns for its owners. Born as one of seven, he was working in the textile industry by the age of 10 and managing a mill in Manchester by 21. In 1799, at age 28, he purchased the New Lanark cotton mills from his new father-in-law. New Lanark was a series of 4 cotton textile mills powered by the flow of the River Clyde. The mill came with a village housing its thousand plus workers. He paid £60,000 for New Lanark with the backing of several investors from Manchester.

Owen believed education was vital to lift the three quarters of the British population out of poverty. He also had the foresight that well paid workers are new consumers, driving demand across the economy.

In 1799, working conditions in the UK were harsh, so the changes he made for the better can seem less than revolutionary today. When he took over, the majority of the employees were children. Changes he made included lifting minimum working age from 5 to 10, cutting workdays to 10½ hours (one of the shortest in the UK), and banning physical punishment of workers. He provided education for the children in a newly built school, nursery care for working mothers, free baths and medical care, and a company store that sold at a discount due to its bulk purchases. He also set up a credit union.

The mills’ output of yarn rose 31% over the 10 years to 1811. And based on the original purchase price, the mills were generating a return on investment around 15% by then. The company was one of the most productive mills in the country, and a showcase for balancing employee interests with profit.

However, given Owen’s reliance on third party investors, not all went smoothly. The first and second sets of backers were not happy with the money spent on employees. Owen scrambled and his third group of investors, which included some wealthy and reform-minded Quakers (a religion also known as The Friends), agreed to a low yield of 5% on their investment. The business flourished until 1824 when Owen sold the mills. From then on, the business drifted.

View - The goals of savers and investment managers have evolved to demand more effective social delivery alongside a healthy profit. We believe consistent goals from owners are key to encourage value maximization over a long term horizon. This is well served by genuine long term investors, who must be able to differentiate feasibility of costs associated with long term goals from smoke screens for poor performance. We see no short cut from experience and deep research for owners of any business.

Investors need to wake up and realize they are a key part of the solution as much as they are part of the problem.

1. http://umich.edu/~thecore/doc/Friedman.pdf

Certain information ©2019 MSCI ESG Research LLC. This report contains “Information” sourced from MSCI ESG Research LLC, or its affiliates or information providers (the “ESG Parties”). The Information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced or redisseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or a component of any financial instruments or products or indices. Although they obtain information from sources they consider reliable, none of the ESG Parties warrants or guarantees the originality, accuracy and/or completeness, of any data herein and expressly disclaim all express or implied warranties, including those of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such, nor should it be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance, analysis, forecast or prediction. None of the ESG Parties shall have any liability for any errors or omissions in connection with any data herein, or any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages.