China is running out of options

Quality Growth Boutique

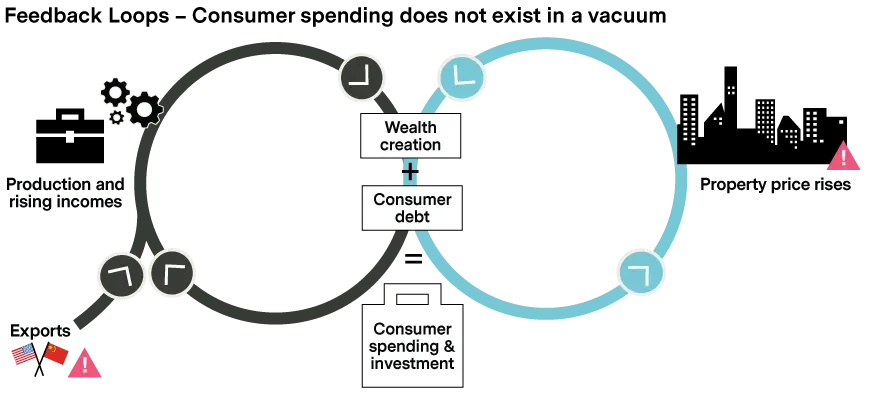

In economics, locking in gains following a spectacular growth phase is rare – but it can happen. China’s economy has grown dramatically over the past 20 years. It now represents both a cornerstone risk and an opportunity for Emerging Market investors. To maintain momentum, and limited by its debt burden, China’s growth engine is increasingly relying on the single cylinder of consumer spending – which delivered two thirds of its GDP growth in the first quarter 2019. Consumer confidence has been lifted by rapidly rising incomes alongside a long run in property prices. Both of these drivers now face challenges.

How much do you think a simple 90m² (970 square feet) two bedroom apartment located one hour from downtown Shanghai would cost? US$250,000? ... try US$1,000,000. The property market is the anchor for a number of areas of the Chinese economy – and it is hot – we need to check the red flag.

Real estate and exports are two drivers of consumption that give us cause for pause. Both are important parts of the wealth creation loop that has underwritten the dramatic growth in spending. In this blog, we take a look at why China’s heated and rising property prices seem unsustainable. We will look at changes that the trade war could deliver in a later blog.

Consumers’ animal spirits tend to spend more when optimistic – often underwritten by rising incomes, a stable outlook for jobs, and long periods of rising property prices. All of these variables have been in place in China. Job stability and wages have benefited from the country’s huge export of goods and services, which accounted for 19.5% of GDP in 2019 – as well as the domestic demand created by confident consumers. And average home prices have more than doubled (up 137%) in the past 10 years. But on the flip side, animal spirits tend to go into their shell, cut spending and pay down debt when nervous about jobs or wealth.

Huge lift for consumers

Chinese consumption has risen alongside a surge in disposable income as millions of new jobs were created after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Over the last ten years, average disposable income rose at an average of 11% a year – a 180% increase in US dollar terms – supported by massive domestic infrastructure investment. This good experience was leveraged by consumers and household debt reached an all-time high of 53% of GDP in 2018, according to CEIC data.

It is important to recognize that China as a nation remains one of the world’s highest savers. Reasons for high consumer savings include: larger home purchase down payments, shifts in the retirement burden from government to consumers, and less job security offered by the state. But, as income inequality has risen, there is a notable difference in the distribution of savings. The IMF estimated that in 2013 the top decile of earners saved 50% of their income compared to 20% for the bottom decile. Again, the market narrows – the wealthy are better positioned to weather a slowdown, but it’s the masses that matter in economic direction.

Property

Property plays a central role in China’s economy. Land sales have provided significant funding for local government budgets (around 85% of budgeted spending is done through local governments1). Home construction has delivered millions of jobs. Property provides significant collateral, securing much of the debt issued by the country’s banks. But property has also become an important investment asset class for savers. Chinese savers cannot diversify their savings internationally due to the barriers of a closed capital account. Domestically, there are relatively few less risky investment choices, given the early stage of the capital markets. So property offers an attractive and tangible alternative.

Property in China has become expensive. Just on common sense $1 million for a modest apartment in Shanghai does not seem mid-cycle for a middle-income country – even one going places. The high prices have created a hazard. Yet so many analysts seem to miss this point by focusing on traditional metrics such as affordability (measured as income to price) or ignore it all together as if property values are in a vacuum.

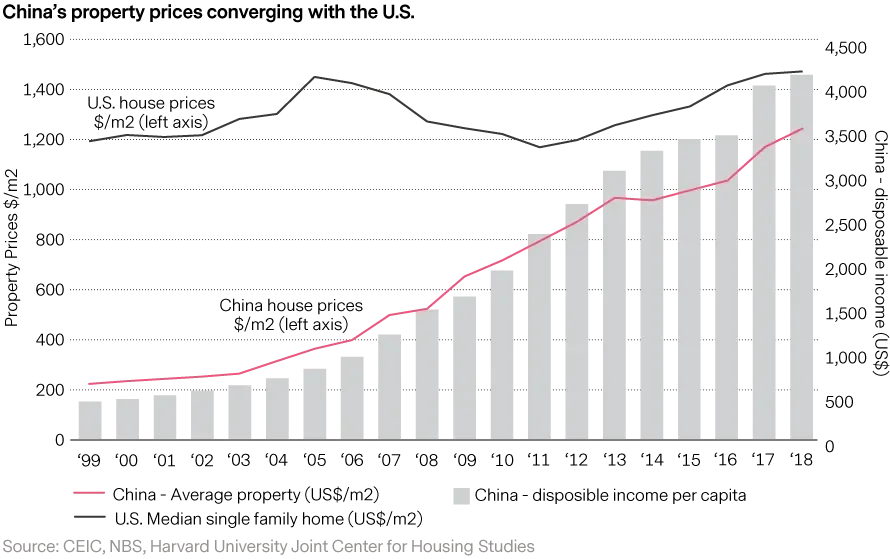

Average property prices per square meter (m²) nationwide rose at a compound rate of 9% a year over the decade to 2018, just below 11% for disposable income. As a result, the price/income ratio fell, which makes the nearly 140% increase in property prices over the same period easy to justify – or miss.

For context, a comparison paints an interesting picture. Relative to the U.S. market2, the average price/m2 of a Chinese property has risen from 20% in 2001, to 84% by 2018 (see chart) and the U.S. market has been healthy. Yet in 2018, Chinese disposable income per capita of $4,100 was less than one tenth the $48,700 of the U.S. Relative to the U.S. at least, Chinese real estate looks richly priced.

Within China, prices vary by city, but the big four Tier 1 cities have become very expensive. In 2018, the price/household income ratio for Guangzhou was 7x, Beijing and Shanghai were 12x, and Shenzhen reached a staggering 20x, according to estimates from JP Morgan3. This compares to the U.S., where the median 2018 price/household income was 4x4.

Watching Red Flags

Planning and building infrastructure, such as bridges and roads, can be done by order. But the economy becomes more complex to manage as it evolves and consumers play a greater role. Consumers cannot be commanded to remain optimistic. Delivering confidence to the population becomes increasingly important in keeping the consumer cylinder turning.

Alongside wages, real estate prices are clearly an important pillar for the Chinese economy. This is not missed by the authorities and we assume they will do whatever they can to avoid a property sell off. Given the controls the Chinese leaders have over the economy, they might well be able to stave off a housing bust such as the one the U.S. was unable to avoid in 2008. However, we find it hard to believe that consumers will get much more upside surprise from this starting point.

For now, consumer confidence is holding, helped by recent stimulus including tax cuts to lower income earners and VAT. But the red caution flags are up. Take care on the banks and real estate companies. We just don’t see a predictable upside for leveraged exposure to Chinese real estate. Companies selling anything but the most conspicuous discretionary items to the wealthy, with their deeper savings, should stand to benefit from less cyclicality. There certainly appears to be more attractive areas to invest into across the Emerging Markets, and within China itself, than businesses reliant indirectly on Chinese real estate.

1. Source: IMF

2. Source: That state of the nation’s housing 2019 from the joint center for housing studies of Harvard University. Referring to median sales price of single-family homes in 2018 US dollars.

3. JP Morgan also sourced NBS, CREIS, and CEIC. Estimates based on home prices from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) for an average 90m2 property with household income calculated as disposable income per capita x average household size x 1.2 for grey income.

4. Source: The state of the nation’s housing 2019 from the joint center for housing studies of Harvard University.