The China paradox: underrepresented or too dominant in emerging market equities?

Conviction Equities Boutique

Since China began opening and reforming its economy in 1978, its growth in gross domestic product (GDP) has averaged over nine percent per year and more than 800 million people have lifted themselves out of poverty1. In 2022, China accounted for just over 18.6 percent of the world economy, making it the second largest by nominal GDP after the United States2. This year, the International Monetary Fund expects just over one-third of global economic growth to come from China. While the past decade played out the “Chinese paradox” of its stock market (which saw a +4.3 percent annualized return for the period 31.12.2011 – 31.12.2022) not keeping pace with GDP growth (+6.6 percent annualized over the same period3), the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges have grown strongly in terms of capitalization and importance. With a combined market capitalization of USD 11.6 trillion, the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges are now the second largest in the world, behind the US stock exchanges of NYSE and NASDAQ and their combined market capitalization of USD 44.4 trillion4.

The weight of Chinese equities in the MSCI Emerging Market Index has more than doubled since 2011, increasing from 15.3 percent to 30.8 percent5. However, as China's capital markets are still not fully accessible to international investors, the market capitalization of shares listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen is only weighted by an allocation factor of 20 percent. If this factor were increased to 100 percent, China's weight in the MSCI EM Index would rise to 44 percent, meaning it would account for almost half of the index. This highlights a second paradox of the Chinese stock market: it is dominant but also underrepresented at the same time.

During the past three years, however, Chinese politics and the economy have changed. President Xi Jinping’s current focus appears to be setting a sustainable basis for the continued expansion of China’s global influence and overcoming the "middle-income trap" via an economy that generates greater added value and provides a better standard of living for its people (common prosperity). Recent years have seen crackdowns on major technology companies, such as Alibaba, indicating that wealth inequality and dominant market positions of private companies are frowned upon. At the same time, interest in a planned socialist economy appears to be growing. This is playing out in a restructuring of GDP away from infrastructure and real estate investments toward selected strategic industrial sectors and the increasing consumption of the domestic middle class. Likely to result in a lower future growth rate, this restructuring understandably triggers uncertainty and insecurity among many western investors.

Five patterns of investor response

Based on these contrasting developments and their interpretation, investors are increasingly looking at different ways to incorporate China into their portfolio. The plain-vanilla approach of adopting a global emerging market (EM) equity framework in which China sits is starting to be challenged. Based on our conversations with investors around the globe, we see five broad approaches emerging:

1. Taking full control: Many investors want complete control of their exposure to Chinese equities and therefore set a target within their overall strategic asset allocation (SAA). This allows the level of exposure to be changed in line with comfort levels, as they either rise or fall. It requires separating China out of the overall global emerging market portfolio, akin to having a separate US equity allocation sitting alongside a Global ex-US equity portfolio. Although it makes intuitive sense, implementing such an approach in an active portfolio has not been straightforward during the past few years as product availability has been limited.

2. Limit exposure: A more cautious interpretation or a lower risk appetite may lead investors to limit the weighting to current levels. Similar to the first option, this approach allows the investor to take control by effectively setting a ceiling for the Chinese equity exposure within their overall portfolio. Controlling the level of Chinese equity exposure can best be achieved by separating China from global EM equity.

3. Reduce exposure: Some investors with a very long-term orientation have told us they expect lower levels of Chinese economic growth, driven by deteriorating demographics and comparatively better structural growth opportunities in other emerging countries, such as India and Indonesia. They are therefore making a conscious decision to reduce their exposure to China. Once again, separating China from global EM equities makes this option more operationally feasible.

4. Maintain the status quo: In this scenario, the investor has examined the issues and decides to continue investing in a global EM portfolio that includes China. This implies comfort with the following scenarios: an inclusion factor for Chinese equities nearing 100 percent and a Chinese equity market that’s even more dominant in both the benchmark and the investor’s own portfolio.

5. Zero exposure: The fifth and most extreme option is the total removal of Chinese stocks from a client’s portfolio. In our experience, this type of approach is rare and, if enacted, tends to be driven by ethical opinions on topics such as autocracy, human rights violations, freedom of expression, and the social surveillance of citizens. In this approach, return considerations are firmly in the background of the investor’s mind – that is, the possible loss of return is consciously accepted.

Can the past performance of EM ex-China guide investors?

Changing the structure of your EM equity portfolio is a significant decision and it’s helpful to first consider how the EM ex-China approach has fared in the past.

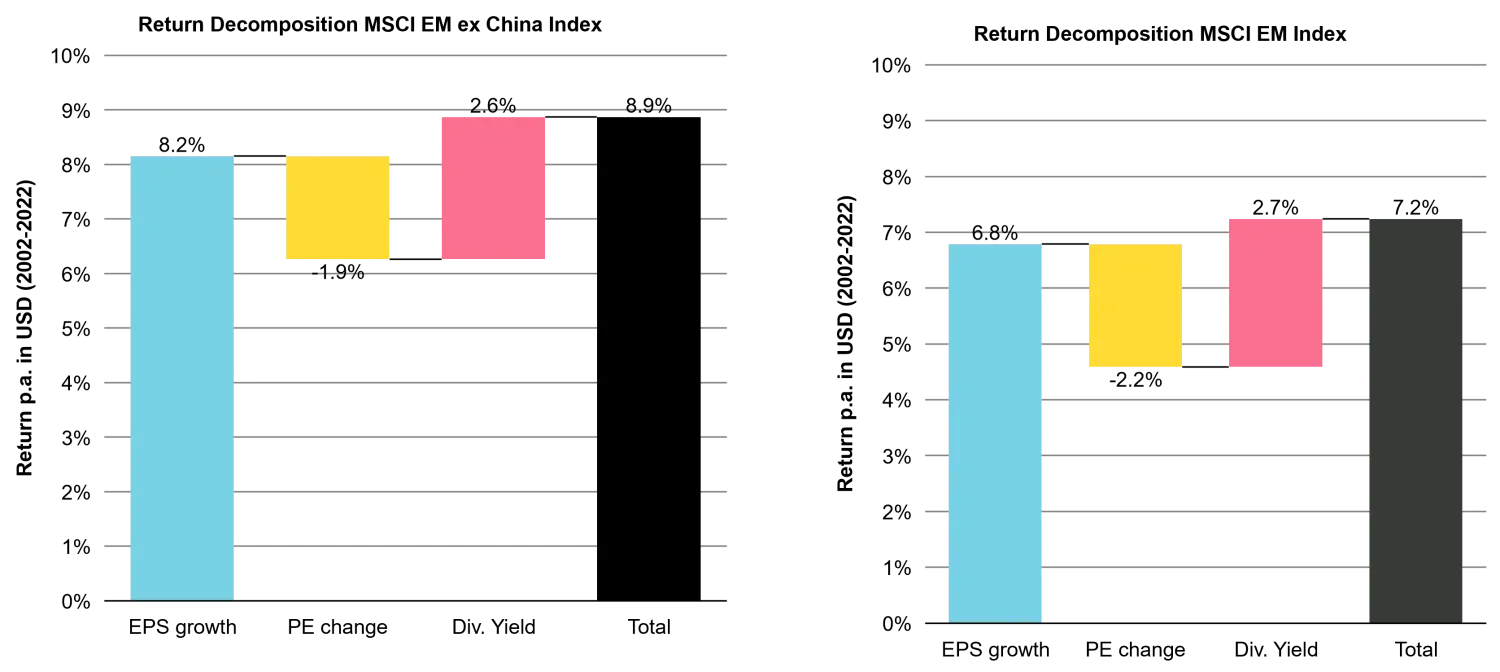

Let’s start by looking at the annualized return for the period 2002-2022 (in USD): the MSCI EM Index returned 8.9 percent compared to 7.2 percent for the MSCI EM ex-China Index6, which makes sense given the Chinese economy’s strong growth in both absolute and relative terms during this period. Breaking down the return – into the components of earnings per share, earnings growth, valuation (P/E) change, and dividend yield – shows that valuations declined by a good two percent annually, both with and without China. Given that lower growth justifies a lower valuation, this can be explained by the declining (or even negative) growth premium of all emerging markets, compared to the developed world, during this period. In addition, the past five years saw the MSCI EM ex-China index display slightly higher volatility.

Thus, it can be argued that a switch to "ex-China" has historically not paid off. That said, it is impossible to forecast the future change in the risk/return profile for EM ex-China.

Historical return decomposition and volaltility

Past performace is not a reliable indicator or future performace

Source: Vontobel Asset Management data, as of 31.05.2023

Excluding China doesn’t necessarily eliminate its influence

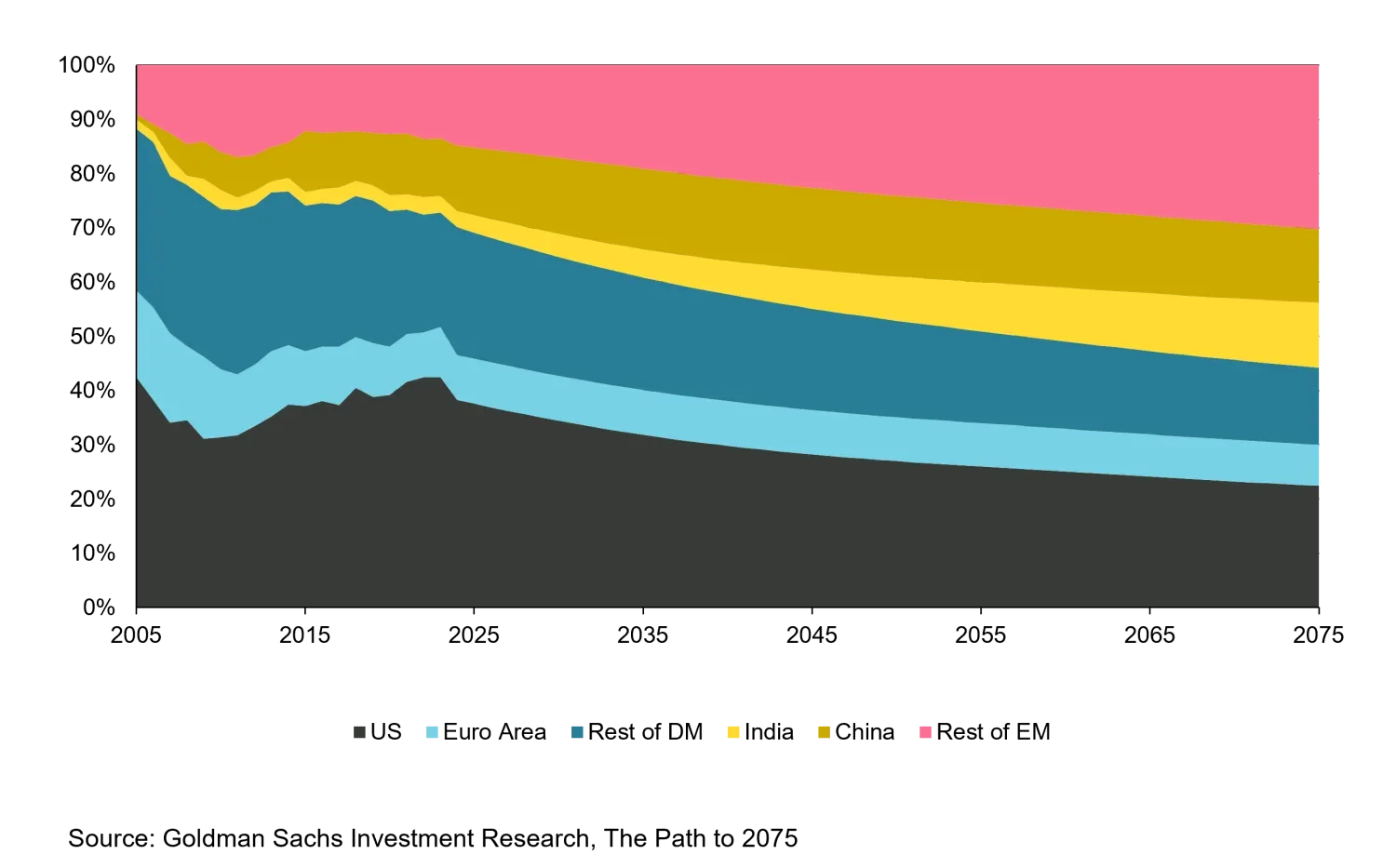

An indication of the long-term development of an emerging market ex-China approach could come from looking at the link between expected population growth, economic growth, and stock market capitalization. While China's population is shrinking, decades of strong population growth remain forecast for nations such as India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Indonesia. Economies with growing populations are expected to display stronger economic growth and – as GDP per capita means an increase in income and wealth, which in turn will be invested in stocks via pension assets – the market capitalization of stock exchanges could even increase disproportionately to population growth. This scenario would see India overtake China in terms of capitalization from around 2050 and the abovementioned countries would be weighted more heavily in the MSCI EM index7. However, it is worth bearing in mind that emerging countries such as Nigeria and Pakistan are either not accessible to many professional investors or don’t yet have a stock market compliant with institutional standards.

Share of Global Market Cap by Region/Country

Imports and exports to and from the West are, in aggregate, even more important for most emerging economies than those to and from China. Moreover, since the Covid-pandemic, China's economic cycle has decoupled from that of other countries, which in turn has reduced the sensitivity of corporate profits to changes in profits and economic activity in China. However, if investors decide to forgo China in their emerging markets approach – either in whole or in part – they should not forget just how intertwined its economy is with the global one and those of other emerging markets. Consider that China is now the largest single trading partner for almost all countries in Asia, South America and Africa. In Chile, for example, copper exports account for 15 percent of GDP and two-thirds are sent to China8.

Which approach is the most suitable?

There is no right or wrong answer to this question. When considering how to include China in an EM portfolio, as with any investment decision, it must make sense for the investor and correspond to individual circumstances and beliefs.

Our approach at mtx is to provide clients with tools that enable them to build the type of EM equity portfolio that they desire. We do this by offering multiple strategies underpinned by one consistent investment philosophy and our four-pillar investment process. Since late 2021 this includes an mtx EM ex-China strategy for investors wishing to separate China from the rest of their EM equity allocation. This portfolio exhibits the same style characteristics that you would expect to see from any mtx strategy, namely higher quality at reasonable valuations, and can, of course, sit neatly alongside a client’s dedicated China equity exposure.

Overall, we caution against a complete removal of Chinese equities from EM portfolios given China’s importance to the world’s economy. While the last few years have been difficult for the Chinese stock market, completely removing exposure from the second largest market in the world is, in our view, an extreme move. However, providing ex-China solutions allows clients to take control and make allocation decisions suited to their individual circumstances. In our view, increasing the ability to individualize investment approaches is a very positive development for investors.

1 As measured by the CSI 300 Index. Source: The World Bank, 20. April 2023,

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview

2 Source: IMF, 1. May 2023,

https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/05/01/asia-poised-to-drive-global-economic-growth-boosted-by-chinas-reopening

3 Source: Vontobel Asset Management, Bloomberg, data as of 31.07.2023

4 Source: Statista, data as of 30.04.2023,

https://www.statista.com/statistics/270126/largest-stock-exchange-operators-by-market-capitalization-of-listed-companies/

5 Source: MSCI, Bloomberg; data as of 31.07.2023

6 Source: Vontobel Asset Management, Factset ; data as of 31.05.2023

7 Source: Goldman Sachs Investment Research, The Path to 2075 — Capital Market Size and Opportunity, 08.06.2023

8 Source: S&P Global Ratings,

https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/230201-which-emerging-markets-benefit-the-most-from-a-reopening-in-china-12623592#:~:text=The%20emerging%20markets%20(EMs)%20that,and%20include%20Thailand%20and%20Vietnam.

Important Information:

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Asset allocation and diversification do not guarantee a profit or protect against a loss. Indices are unmanaged; no fees or expenses are reflected; and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Forward-looking statements regarding future events or the financial performance of countries, markets and/or investments are based on a variety of estimates and assumptions. There can be no assurance that such assumptions will prove accurate, and actual results may differ materially. The inclusion of forecasts should not be regarded as an indication that Vontobel considers the projections to be a reliable prediction of future events and should not be relied upon as such.