Conviction Equities

Concentrated and fundamentally driven high-conviction equity portfolios managed by four teams specialized in emerging markets, impact investing, thematic investing, and Switzerland.

Jean-Louis Nakamura, Head of Vontobel Conviction Equities Boutique, shares his thoughts on how investors should approach the changing tide in China

Faced with a weakened economy, the Chinese government has made multiple policy moves lately, in line with its pledge to support it, revive the stock market, and contain the property crisis. Summer saw successive cuts in various policy rates and an announcement on August 28 that the levy charged on stock trades would be cut by 50 percent, from 0.1 percent to 0.05 percent1.

While policymakers seem fully aware of and increasingly concerned by the deflationary dynamic at work in key segments of China’s economy, they’re not (yet) willing to deliver the “whatever it takes” approach employed in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis and by major developed economies during the European debt crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic.

What this current situation reflects is that over the last three to four years, China has completely rewritten its policy playbook. The persistent nature of this rewriting and its long-term impact on investment cannot be ignored further.

The last quarter century has seen China perform a fantastic catch-up in its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. It delivered this by fostering a robust and near-free market economy, supported by strong fixed/infrastructure investments to prompt capital deepening. As needed, this was coupled with ultra-bold macro counter-cyclical policies to either boost or cool its business cycle. The speed and magnitude of GDP development were mainly driven by private companies led by true entrepreneurs. Until three years ago, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were seen as the weaker link in the Chinese economic chain.

But the rapid nature of this development was not without its less-than-savory consequences. New and significant challenges arose during this period, including an imbalance in and overconcentration of wealth, monopolistic conglomerates, and excessive leverage, especially at the corporate and local government level.

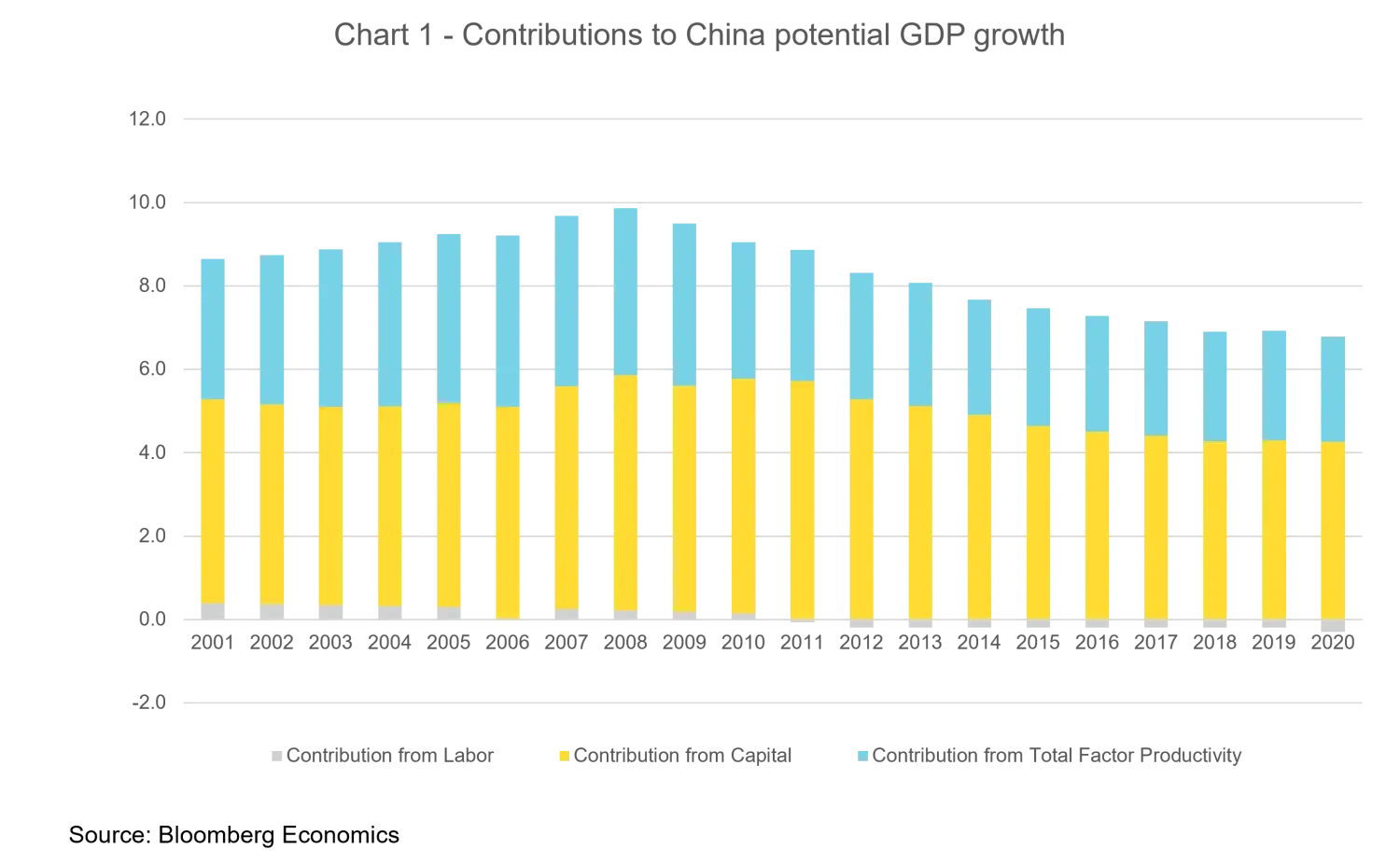

Taking a more granular look: land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship are the four factors influencing a country’s productivity, and excessive accumulation of fixed capital resulted in their rapid slowdown during this period. Simultaneously, as chart 1 indicates, China’s population has been aging very rapidly, leading to a negative labor contribution to potential GDP growth. In parallel, easy access to leverage and under-regulation of financial services fed the domestic market’s boom and bust period of 2014-2015, putting the savings of “average” citizens at risk. And finally, but no less importantly, the dramatic environmental toll of this rapid development, including an eight-fold growth in CO2 emissions from 2001-2022,2 continues to pose a major risk and is an issue China must contend with in the years to come.

It was only towards the beginning of his second mandate that President Xi Jinping, who began his presidency in 2013, signaled the shift in paradigm and priorities for the long-term development of China. His 2017 report to the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) stated intentions to redefine priorities away from “unconstrained reform and opening” to a new era focused on solving the “imbalances of development” – a response to some of the challenges mentioned above and one that introduced the concept of “common prosperity"3.

However, in the absence of a concrete economic policy translation, this rhetoric initially remained either unnoticed or was simply ignored. It took almost three years before the Chinese government began flushing various parts of the Chinese “new economy” with waves of restrictions and penalties. This included the much-publicized hunt for “anti-social” behaviors allegedly promoted on social media applications like Douyin and video games such as Tencent; the overnight shutdown of private online education services like Tomorrow Advancing Life (TAL); and the fines and other crackdowns on data platforms (Ant financials/Ali pay/We pay) and gig economy services (Baba, Meituan). In addition, rules for property acquisition and mortgage access were amended with the argument that “houses are for living, not for speculating” – actions that, regardless of the intention, led directly to the choking of the real estate market in late 2021.

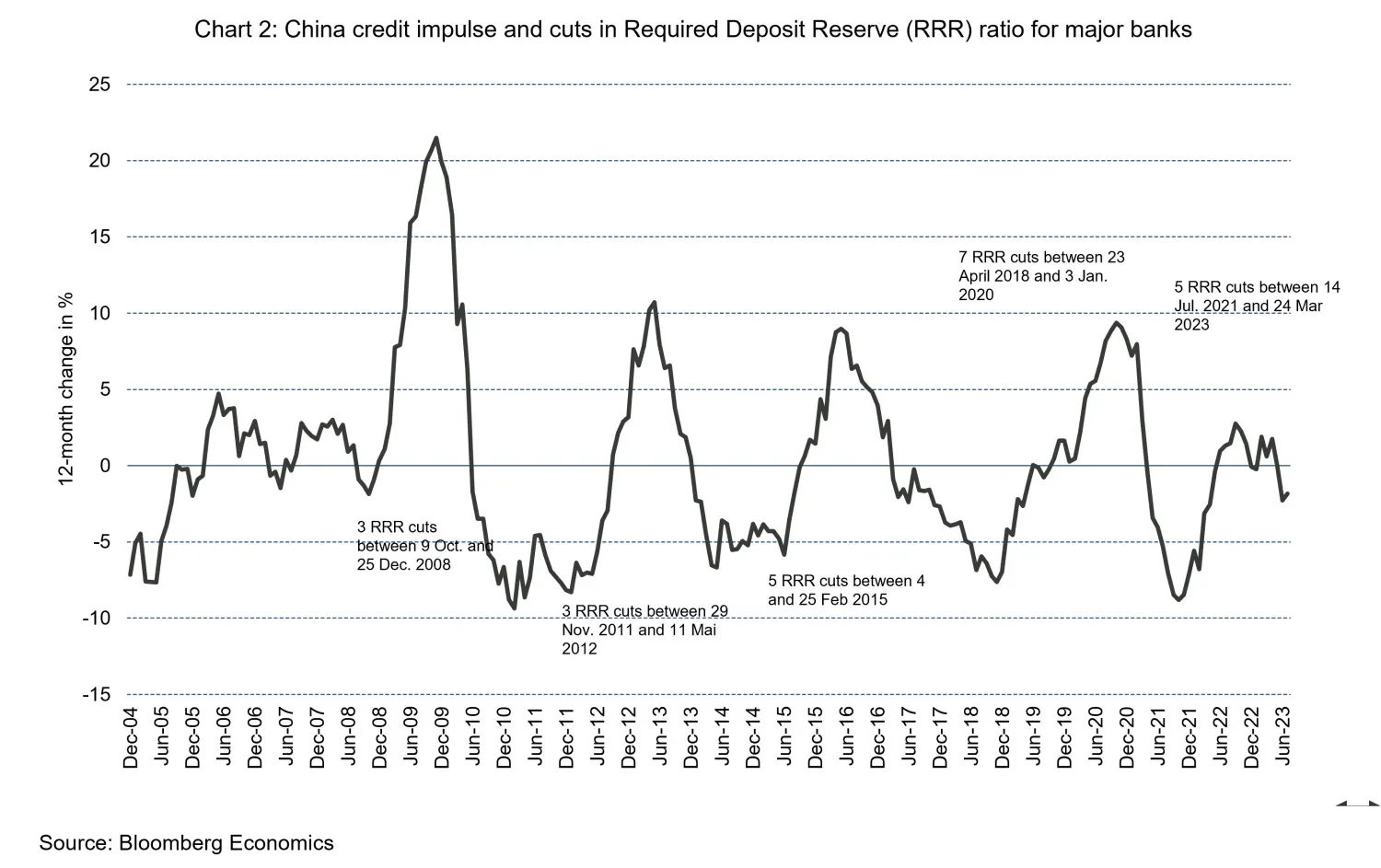

On the macro policy side, changes in the management of cyclical slowdowns have been more rampant, if less significant, but still represent a sharp disruption from Beijing’s previous policies. For example, in the past, the “miracle potion” to lift local production and demand during cyclical lows was a rapid and well-telegraphed combination of liquidity injections (through cuts in the required deposit reserve ratio), cuts in policy rates, and sizeable fiscal fine tuning of both the volume and calendar for local government bond quota disbursements (see chart 2). In sharp contrast, over the last few years, the support measures taken by Chinese authorities to counter significant exogenous and endogenous shocks to the local economy have remained remarkably subdued. Even more striking, the dramatic decision to put some of the country’s major cities under complete Covid-19-related lockdowns in 2022, while the rest of the world was learning how to “live with the virus”, clearly demonstrated that short-term GDP growth objectives had been derated far behind other social priorities.

Economists and strategists have been, on average, slow to understand the depth and persistent nature of those changes. At first, many suspected that they reflected a cynical political positioning ahead of the 2022 Congress in order to secure the “visionary” role of President Xi and an unprecedented third mandate. Retrospectively, it is possible to identify key trigger events that could explain the spectacular materialization of new and apparently deep-rooted convictions shared by President Xi and some of his closest advisers, who have always been concerned with building a more sustainable and inclusive model of development than the one adopted in the West.

Historically speaking, the concept of social stability has been perceived as the major source of legitimacy for the rule of the CCP by many Chinese. When the US Federal Reserve failed to normalize monetary and credit conditions in late 2018, this may have added fuel to the fire for those concerned about being trapped in a never-ending liquidity-dependent economy with a growing disconnection between financial and economic returns, which would feed into an unstoppable growth in wealth inequality.

Disappointing economic data mounted through early August. Coupled with the renewed weakness in the property sector and encouraged by the recent pullback of China’s Zero-Covid policy when its economic and social costs became too obvious, many speculated that China would revert to some of the economic strategies it deployed in the last couple of decades and unleash a wave of significant measures that back-pedal on its policy of the last few years. The most recent move to prevent a collapse in the real estate sector – lowering existing mortgage loan rates and including previous mortgage borrowers in the list of first-time buyers (provided they have sold their previous properties)—was already much bolder than the support measures seen over the last 18 months.

However, many economists would argue that those measures remain far from the kind of radical policies needed to pull the Chinese economy out of its current deflationary trajectory. As we do not expect any dramatic short-term collapse of China’s domestic situation, it is likely some of the economic data that worsened the fastest over the past few months will stabilize or even rebound in the near term. Should this be the case, Chinese authorities will have even less of an incentive to move more aggressively.

Only a significant risk of social destabilization, triggered by a massive social crisis, could trigger a U-turn in policymakers’ mindset, though this seems unlikely in the current environment. Taking the high youth unemployment rate as an example (21.3 percent, or as high as 47 percent to include those “not in education, employment, or training”)4, the majority in this group, aged 16 to 24, have university degrees and receive financial support from their families. As a result, many may be in the position to delay their entry into the labor market and “chewing on the elderly” as part of the “lying flat” phenomenon. This also means they are unlikely to be the root of social unrest, at least in the short term. This situation lies in stark contrast to 2008, when workers along the eastern manufacturing belt staged mass protests after losing their jobs. China reacted with a 4 trillion yuan (USD 588 billion) stimulus plan to create work for an estimated 20 million migrant workers5.

With little incentive to step back on his political doctrine, it seems President Xi will not change course regarding China’s new policy playbook anytime soon. In March, President Xi formally began his unprecedented third term, having both secured and consolidated the balance of power and influence within the CCP at the 20th National Congress last October. At this stage, with President Xi’s firm grip on power, it seems that only some source of social instability could spark a rethink of the current ideological stance. And as I noted above, this seems unlikely.

So how should investors approach the changing tide in China? It’s essential that they understand, accept, and adjust to the new playbook, keeping in mind four major macro and micro implications:

As a response to increasing global demand but in addition its own climate-related concerns, China will remain at the helm of many of the future global leading companies in the energy/AI transition. However, the conductivity between current size, sales growth, earnings, and stocks’ returns might be more complex to apprehend than before.

Growth premiums will no longer lie in market beta. Instead, it will be found in the capacity to pick up future winners, in the right stream of business, and in a positioning that might provide shelter from unpredictable policy interference. In a slower-growing economy, investors – especially retail-dominated domestic ones – will chase after faster-growing businesses. The bottom line is that it’s best to accept and understand the CCP’s current policies: Future winners will be found in policy-supported themes but the focus must remain on profitability and sustainability as subsidies and policy favors might translate into regular overcapacity or price wars.

Other industries will either face a lower growth dynamic or the risk of permanent government interference, with SOEs displaying rather stable cash flow and earnings quality being persistently favored over fast- earning private companies. While SOEs massively underperformed in the A-shares market during the 2011-2020 decade (merely +12 percent total return vs. 2.5 times for privately-owned enterprises), they have experienced a spectacular catch-up since early 2021, performing on average by more than 20 percent while privately owned companies were suffering a massive derating by more than 50 percent8.

As mentioned above, size must be evaluated differently than before, as it might even be a factor for discount in non-policy-supported industries. Authorities will continue to fight perceived predatory behaviors. In fast-growing fields like tech, agility and innovation ability within a well-identified cluster might prove to be stronger and more persistent criteria for quality. Cash holding and funding capacity independent from banking/markets should also be more discriminatory.

We believe that if investors pick the winning businesses under this new policy regime, investing in China could even prove more rewarding than before, especially given the lower volatility/higher diversification, with the rest of the global ecosystem tagged to the segment of the Chinese stock market that’s sheltered from political interference and geopolitical risk. But once again, this requires investors to follow, understand, and adjust to the new playbook.

Finally, there might be a growing need for global investors to tailor their own allocation to China, which, from multiple angles, can be seen as either too high or too low in current global or emerging indices. Facilitated access to Emerging ex-China solutions, along with China and/or China A only investment strategies, can answer this strategic objective9.

1.

https://www.ft.com/content/29166593-aece-423d-a62b-584079d7d21b

2.

China Carbon (CO2) Emissions 1990-2023

. www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 2023-09-25. .

3. See “Xi Jiping, the rise of ideological man, and the acceleration of radical change in China”, The Hon. Dr Kevin Rudd AC, Asia Society Policy Institute, October 24, 2022.

4.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-07-23/china-s-actual-youth-unemployment-is-a-lot-higher

5.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-07-23/china-s-actual-youth-unemployment-is-a-lot-higher

6.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-05/china-slowdown-means-it-may-never-overtake-us-economy-be-says

7.

https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/news/mediarusources/202202/t20220218_1315947.html

8.

https://www.premia-partners.com/insight/china-soes-the-journey-to-extract-values-from-the-re-rating-and-revaluation-trajectory

9.

https://am.vontobel.com/insights/the-china-paradox-underrepresented-or-too-dominant-in-emerging-market-equities