Munger Was Right, After All

Quality Growth Boutique

When asked to describe their approach to investing, Buffett’s brilliant partner Charlie Munger famously remarked that the approach was “simple, but not easy.” After nearly 40 years of investing, I have come to more fully appreciate the wisdom of Munger’s words. When I first started out in the asset management business in the early 1980s, and first “discovered” the writings of Warren Buffett, I almost felt that I had happened upon the Holy Grail. Buffett‘s idea of buying good quality companies at prices comfortably below their INTRINSIC VALUE seemed logical, and it was intellectually appealing because it implied that the “true” absolute worth of a security could be determined. In doing so, one could truly INVEST, not just speculate.

Many years later, I listen disdainfully as so many investors allege to know the intrinsic value of such large numbers of stocks in their portfolios. The term “intrinsic value” is thrown around so loosely. Maybe I have become jaded and cynical, but one thing I have found after examining thousands of companies over time is that there are many challenges in trying to determine what the “true” value of a company is.

Yet despite these challenges, getting valuation at least approximately right is as important as it has ever been, but we strain to see how the ever-higher grinding market environment we are witnessing is acknowledging this reality. The 8 points below outline just a few of those intellectual challenges with respect to valuation.

- In Finance 101 it sounded so simple: the value of any asset is the present value of future cash flows that can be derived from that asset over its lifetime. Well, the lifetime of a financial asset can be pretty long and most investors certainly can’t see out THAT far with any precision. Today’s rapidly changing environment makes this calculation especially challenging.

- Prudent investors typically dare not forecast out beyond a brief intermediate time period, because most of the time that’s about how far out any “certainty” about a company’s business prospects can be had. To give credit to a company for its expected life beyond any intermediate period forecast, investors usually apply a MULTIPLE to the company’s furthest out forecasted earnings per share to give credit for the future growth that will occur in outer years. While the multiple that investors attach is often reasonable, and typically invokes the historic multiple of the stock, the multiple applied cannot be exact and does involve an element of subjectivity.

-

For so-called “bottom up” investors like Buffett and ourselves, whose principal focus is on the merits of each individual security we analyze, we purport not to let macroeconomic factors enter into our analysis principally because we regard the macro as being too unpredictable to be reliably forecastable. A cynical question often posed by many bottom-up types like ourselves is: “Have you ever met a RICH economist?” Unfortunately the macro may not be reliably forecastable, but MACRO MATTERS.

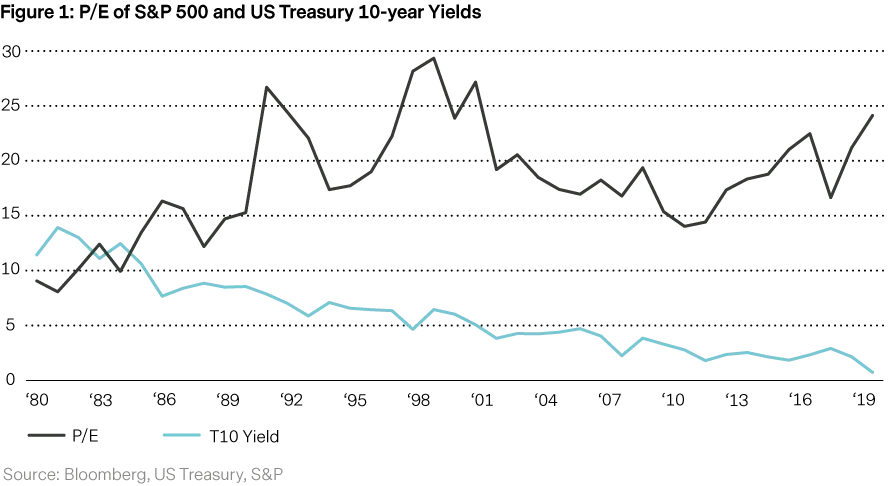

It’s not just the boom bust economic cycles that we have to surf... we can deal with that by buying and holding some of the better quality companies that can weather most storms. But wild fluctuations in interest rates, oftentimes dictated by the equally unforecastable policies of the Federal Reserve, can have a huge impact on the discount rate we use to derive the present value of future cash flows. When I started on Wall Street in pre-Volker days, the price-to-earnings ratio of the market was in single digits because inflation and interest rates were double digits (see Figure 1). Today, of course, we have the reverse with near zero interest rates and much higher stock multiples. As we attempt to look out years into the future, is it prudent to discount a company’s cash flows by TODAY’S extraordinarily low level of interest rates and to assume that today’s level of rates will persist well into the future? Price-to-earnings ratios have ALREADY been huge beneficiaries of the long secular decline in interest rates we have enjoyed since the 1980s; is it possible that a secular trend in the OPPOSITE direction could one day ensue? Even a modest increase in interest rates could suddenly cause a company’s stock price to change from being undervalued to being overvalued.

“ Even a modest increase in interest rates could suddenly cause a company’s stock price to change from being undervalued to being overvalued.”

- I love the Buffett concept of buying companies with “enduring competitive advantages." The problem is, hardly any company has one! A perfect example of a company with such an enduring advantage would be Pharmaceutical Company C, who in theory has just invented a cure for Covid and has a lifetime monopoly patent on the miracle drug. If only we could FIND a slew of companies like these that few other investors have also discovered such that their stock prices were still reasonably valued. It’s hard enough to find a company with a wide “moat” (a competitive advantage), but that advantage must then ENDURE. It must persist over time, or at least over your forecasted cash flow period. But capitalism is very competitive. We all know about Schumpeter’s “creative destruction.” So many of the great companies of the past like Kodak, GE, and IBM, that appeared to have enduring competitive advantages in their day, no longer appear as advantaged and their sagging stock prices now reflect today’s reality. I believe that we at Vontobel, with such a heavy emphasis on buying better quality businesses, have been able to buy a fair amount of companies with reasonably wide moats (Google, Amazon, et. al.) but the burden is on US as investors to make sure these wide moats can persist over time in our brutally competitive capitalist system.

- The simpler the investment thesis, the better. The more variables that come into play for an investment thesis to work, the less likely the percentages are for the desired favorable outcome. But it is not always easy to find these simple, uncomplicated investments. For example, Ford doesn’t fit our investment approach, but if a favorable investment outcome for Ford stock were dependent on just one variable, let’s say the need for the economy to remain robust, and we believed there was an 80% chance of that occurring, then there would be an 80% chance for a favorable investment outcome by owning Ford stock. If however, we not only need a robust economy but we also need Ford to come out with a new model car (which also has an 80% chance of happening we believe) then from Statistics 101 we find that the chance for a favorable outcome for an investment in Ford, now dependent on TWO independent variables, has been reduced to only 64%. Think of how many investments depend on more than just one variable being correct and how many depend on two, three or even more to be rewarded.

- Sometimes, more so in emerging than developed markets, there is simply inadequate disclosure of the information needed to make an informed decision, and one is left with important “unknowns” in making consequential investment decisions.

- PMV, or private market value, a concept advocated by some investors, is not a perfect solution to our challenges either. This concept suggests valuing a company by referring to what other similar companies are selling for in private markets. This is not an unreasonable idea except for the fact that you, the investor are “passing the buck” to the wisdom and efficiency of the stock market in valuing similar companies. In market bubbles or busts, alluding to the relative valuation of other similar companies is not so helpful.

- More of a competitive issue than one dealing with the challenges of correctly valuing a company, but all investors have access to every piece of data at the exact same time today. Years ago, Fidelity’s stellar portfolio manager Peter Lynch used to spend 360 days a year on the road driving around America meeting with CEOs and CFOs and gathering DATA about hundreds of companies. It is entirely plausible that this gave him superior information with which to more accurately value the companies he visited. I am not the only seasoned investor that has remarked that markets today are much more competitive than they were 30 or more years ago. More and more talented, driven competitors have been attracted to the honey pot that Wall Street can be.

Lastly, I want to make a comment about portfolio construction, although again not the direct focus of individual stock valuation. Let’s start off with a question: “Have you ever seen one sentence written or any words spoken by two of the world’s most brilliant investors, Buffett and Munger, about “portfolio optimization“? I haven’t. But I have seen plenty of words written by “Modern Portfolio Theory“ (not to be confused with Modern Monetary Theory!) advocates from the Chicago School and their acolytes which rely on the concept of “beta” as a measure of risk . Beta, of course, is a measure of a stock’s VOLATILITY in relation to the overall market. Without getting into a long discussion here, suffice to say that Buffett has a lot to say about why beta is an inappropriate measure of risk. I prefer Buffett’s definition of risk as “the permanent loss of capital”, and typical “portfolio optimization” approaches that we see others often employing does not speak to this more proper definition.

I could go on and list even more challenges that go into “making the sausage,” that is, trying to truly invest in asset prices that can be pretty confidently determined, but while I am on a rant, let me now turn to a few of the challenges that the BUSINESS of investment management presents that can further muddy the waters.

Most institutions that give money to investment firms to manage have already made an asset allocation decision a priori that they want their funds to be pretty fully invested in stocks at all times. This precludes the use of cash as a residual if the money manager can find few attractively valued stocks that meet the criteria of his investment approach. During asset bubbles and times of very high stock valuations, this may result in the investment manager feeling the pressure of having to invest in the least relatively OVERVALUED stocks, rather than the best quality UNDERVALUED stocks he/she can find. When Buffett could find little of value in the frothy stock market of the late sixties, Buffett simply dissolved his partnership and returned the capital to his investors, rather than engage in such foolish endeavors. Most institutional investors today would be very reluctant to return assets to the client and forfeit their fees on said assets even IF a fully priced equity market precluded them from executing their investment approach in the desired fashion. Is there any surprise then that bubbles develop in the stock market when so much pressure is on asset managers to play what is predominantly a RELATIVE valuation game?

“The experience that comes from looking at thousands of prior ‘case studies’ over the years matters a lot.”

Investment styles can go in and out of favor for years. Studies have been done that show even investors with the very best historical track records can be out of favor and underperform for many years in a row. As clients’ patience wears thin and assets under management continue to erode, the investment manager comes under what the famed investor Jeremy Grantham describes as “existential pressure”: the fear of losing one’s job and being fired. The pressure builds on the manager to capitulate, to dilute his investment style or valuation discipline. I can personally relate to such pressure having had zero exposure to technology in the US fund in 1999 during the dot com bubble when tech came to constitute 40% of the market capitalization of the S&P. Even Buffett was derided on the cover of Barron’s magazine at that time for having “lost it.” (Déjà vu? Buffett is once again being mocked by the “champion” of the no-commissions, free-trading Robinhood platform crowd by one David Portnoy, who recently remarked, “There’s nobody who can argue that Warren Buffett is better at the stock market than I am right now. I am better than he is. That’s a fact.” We’ll see how THAT plays out!) At times like that, it is tempting to just go with the flow and compromise one’s investment discipline because it appears that(those famous words) “this time is different.”

This point is a corollary to the previous point: it is rare to meet a true LONG TERM client (fortunately for us, after years of match making we do have a few). Most clients afford an investment manger a three-year window, at best, after which if underperformance persists, the manager is fired and replaced. (A somewhat ironic point is that the poorer performing manager that is more likely to sooner than later start performing better, if nothing is truly broken in their approach, is replaced with a freshly hot performing manager who is less likely to sustain their current streak indefinitely and perhaps enter their own cooler performing period). But clients do have their OWN job security to worry about, after all, so changes must always be made. There is a potential mismatch though between the investor’s long time horizon when evaluating a company’s future business prospects and the client’s much shorter business time horizon. This is yet another factor that may pressure the manager to compromise his investment style and valuations just for the purpose of staying alive and staying in business. An investor like Buffett has the benefit of permanent “captive” capital with which to invest, unlike most professional money managers. Thus the more patient the investor AND the client, the better, whatever the investment vehicle structure may be.

In Conclusion: It May not be Easy, But It’s Not Impossible

Due to many of the factors alluded to above, such as having to reckon with unpredictable macro phenomena, the difficulty in precisely determining a security’s “intrinsic value” and more, investing has often been referred to as being part science and part art. Books have been written titled “The ART of Investing” because in the end, every investment decision is ultimately an EVALUATION. Although most investment approaches are organized, logical and systematic, the end product, the purchase decision, can never have as much certainty attached to its outcome as would a mathematical proof. Hence, Buffett’s observation that valuation (the intrinsic value of a security) is an APPROXIMATION and his advice that the investor should stay well within his “circle of competence” and be aware of what is and isn’t knowable enough when contemplating any company’s future business prospects. It is INDEED a humbling business.

At Vontobel we are not without tools in our arsenal to help us navigate the often clouded and uncertain investment terrain, which includes the many realities and inherent challenges we have outlined above. We believe we have a SENSIBLE investment paradigm, heavily influenced by our many trips to Omaha over the years. Our approach seeks out better quality, more predictable businesses with strong financials, which gives us a reasonable shot at knowing what a company will look like beyond today. We don’t try to fool ourselves into thinking that we can make forecasts that last for an entire business lifetime, but for at least the next five years of our investment horizon.

To protect us against some of the possible negative unknowns that may arise along the way, we employ a conservative method in computing the fair values of our stocks, such as using a discount rate well above the market rate when doing our present value calculations. (In contrast, some of today’s most aggressive equity investors seem willing to assume that today’s extremely low levels of interest rates will persist indefinitely into the future, thus rationalizing what, in fact, could be high levels of current valuation. In doing so, they also appear willing to make the furthest reaching predictions that fixed income managers struggle to navigate about a completely unknowable future interest rate and inflation environment).

We have a large team of tenured analysts and portfolio managers with many years of experience in the business. And in this business, because each investment outcome is probabilistic, an evaluation, the EXPERIENCE that comes from looking at thousands of prior “case studies” over the years, matters a lot. We are also a global team, capable of analyzing and comparing similar industries across borders. So while fully agreeing with Mr. Munger that solid investment analysis is not easy, it is not impossible, and armed with some of the tools described above, we believe that we have a good chance to help add value by doing that which is POSSIBLE.