Economic moats: growing and defending modern day empires

Quality Growth Boutique

Key takeaways

- Morningstar’s widely accepted definition of moats identifies five main sources of competitive advantages: 1) Intangible Assets, 2) Cost Advantage, 3) Switching Costs, 4) Network Effect, and 5) Efficient Scale.

- In our view, no moat is permanent and today’s moats are constantly under attack. This is why we constantly scrutinize a company’s changing competitive advantages.

- We believe that many companies owned across our portfolios have significant moats. It is our goal to find companies with enduring competitive advantages that may provide our clients with strong, risk-adjusted portfolio returns over the long term.

In legendary investor Warren Buffett’s now famous 1999 Fortune article , he indicates that: “The key to investing is...determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage.” Buffett referred to such advantages as “moats” – believing that they protect a company in the same way a moat does a castle. He also referred to himself as a business analyst first and a securities analyst second, advocating that a business’ quantitative virtues are derived from its qualitative ones.

At Vontobel Quality Growth, we analyze a company’s moat before investing. Since moats can be wide or narrow and change over time, competitive advantages must be constantly monitored. Finding companies with wide moats – i.e., strong and enduring competitive advantages – can be a very lucrative source of investment returns.

Building and defending a moat

Morningstar’s widely accepted definition of moats identifies five main sources of competitive advantages: 1) Intangible Assets, 2) Cost Advantage, 3) Switching Costs, 4) Network Effect, and 5) Efficient Scale. Of course, better companies tend to employ more advantages. Similarly, in academic literature, Harvard Professor Michael Porter identifies two basic types of competitive advantages: cost leadership, where a firm is the low-cost producer in its industry, and differentiation, where a firm is unique along some dimensions that are widely valued by buyers.

In theory, a company with a wide moat can maintain its market share and earn high returns on capital for many years into the future. But finding moats that are capable of true endurance is very difficult. In our view, moats need to be reinforced by astute management, and in the brutal world of capitalism there are always barbarians at the gate.

A look at recent history reveals countless companies that fell prey to competition. In the retail space, Sears and Kmart were dominant in the US for decades until lower cost, more efficient Walmart came along. In the 1980s, before there was Silicon Valley, Route 128 in Boston was loaded with the dominant technology companies of the day like Wang Laboratories and Digital Equipment, which no longer exist. A more contemporary example is Uber, a platform that should be relatively cheap to operate as it brokers deals between buyers and sellers for a fee. Initially, it seemed that Uber’s platform might be the source of an enduring competitive advantage, but unfortunately for Uber, competition has proved relentless. It is locked in a fight with Lyft for rides and Door Dash for food deliveries, among others.

Old moats: remaining relevant amid changing market dynamics

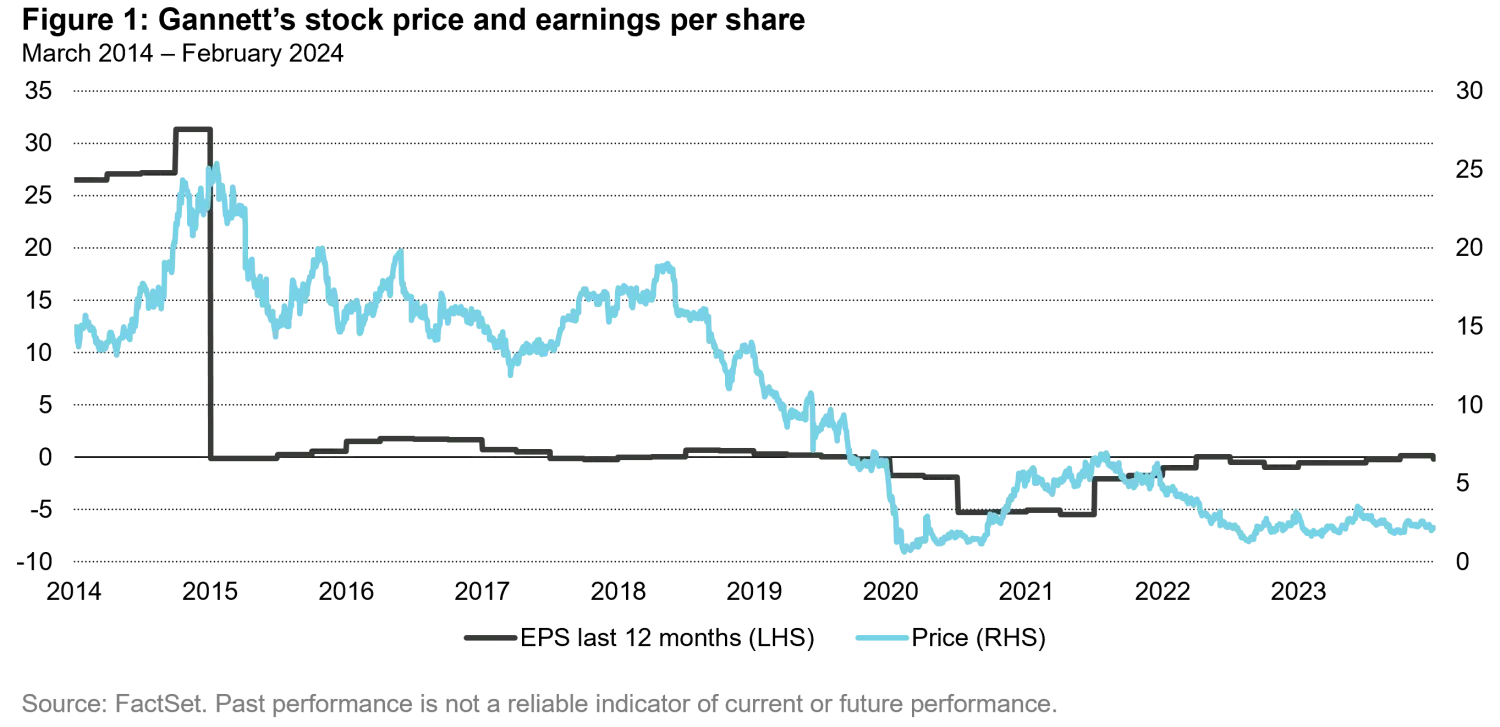

Before the internet, sales of advertising in local newspapers provided a solid business opportunity: an indispensable platform uniting buyers and sellers. Their moat was the network effect. One example is Gannett, a major media company with outlets and publications (including USA Today) in the US and the UK. We owned Gannett’s stock for a long period of time in our quality growth portfolios and Warren Buffett owned many newspaper stocks, including the Washington Post, in Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio.

Over time, technological innovation shrunk and even eliminated the moat such newspaper chains had, with the internet offering new digital platforms to connect buyers and sellers of services. While newspapers have adapted to provide digital editions, the strength of their business model has changed, as illustrated in Figure 1. The lesson from Gannett is that no moat is permanent, which is why we are constantly scrutinizing a company’s changing competitive advantages.

Walgreens is another example of a company we previously owned whose moat has since evaporated. Walgreens emphasized its real estate advantage – finding the perfect location to open a new store, ideally a highly-trafficked street corner. At the time, operating physical drugstores was a cash cow business. The pharmacy was strategically located at the rear of the store, so customers passed through long aisles stocked with shampoo, toothbrushes, and other sundry items on their way to fill prescriptions. Walgreens was a great business until online competitors like Amazon started chipping away at “front end” sales of everyday items.

Changing times do not necessarily translate into collapsed moats

Railroads might be considered another “old moat“ business. Rails have existed for a long time and new ones are not being constructed in the US and Canada. Over the years, rails have been consolidated into four major players: Union Pacific, Burlington Northern, Canadian National, and Canadian Pacific. In fact, in the past year Canadian Pacific acquired Kansas City Southern.

Rails enjoy two kinds of moats. First, their network connects manufacturers of products with consumers across the continent. Second, rails are typically the low-cost producer for the long haul of goods and are less expensive than the next best alternatives, trucks.

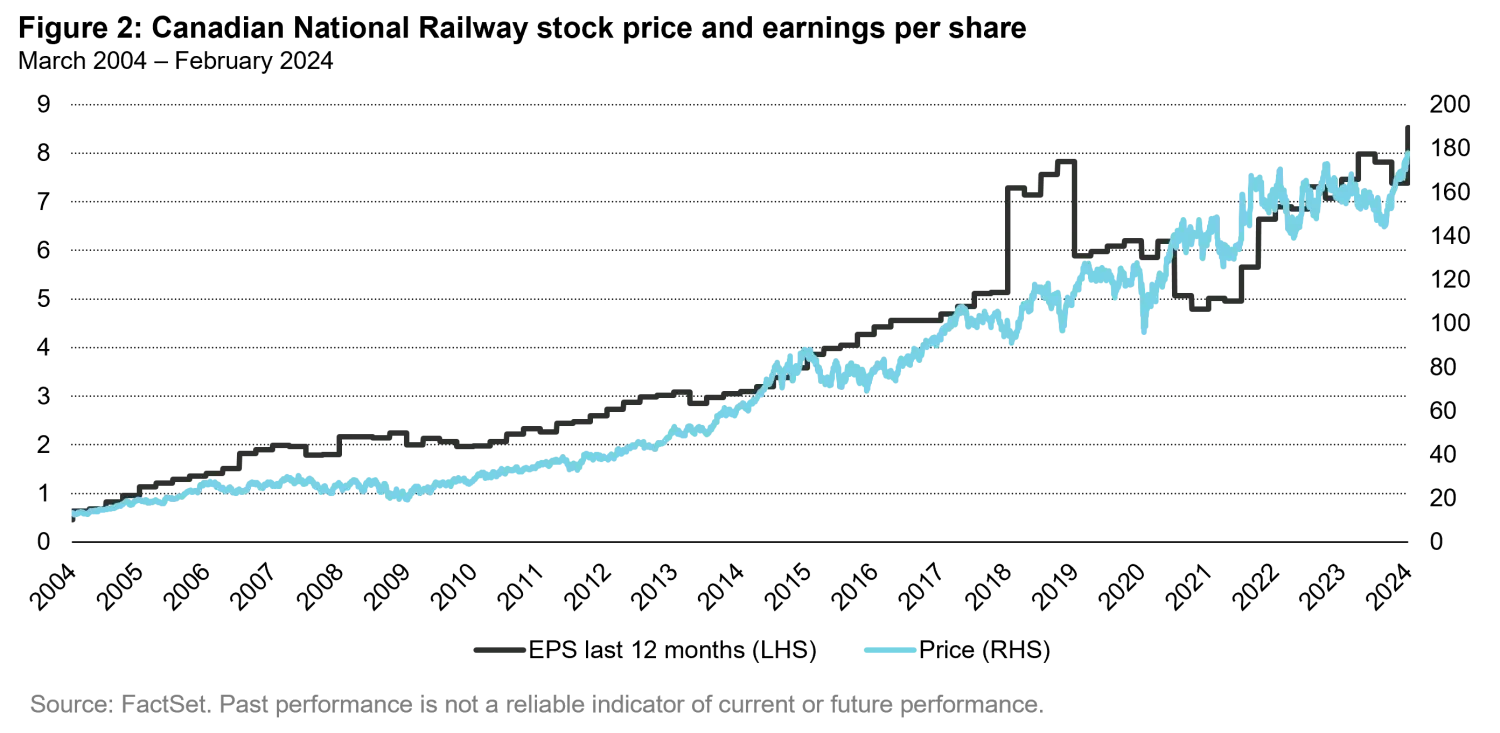

As Canadian National’s stock price shows (Figure 2), old moats do not always shrink or disappear. Despite being capital intensive and subject to cyclical swings in the economy, Canadian National has maintained pricing power, good returns on equity and has been a lucrative stock to own over the long run. It is no wonder that Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway acquired Burlington Northern many years ago adding to his conglomerate of better businesses.

Hermes is another “old moat” example that is thriving and prospering today. Its enduring competitive advantage is its brand as a luxury good, which falls under Morningstar‘s rubric as an intangible asset. Hermes invested in its brand by ensuring the scarcity of its products, spending a large portion of its SG&A on advertising, and paying close attention to the quality of its products. Through these efforts, Hermes maintained a wide moat over the years. Not all luxury brands that once had cachet and formidable moats have been able to do what Hermes has done. For example, Gucci overexpanded over the years, Ferragamo has lost its way and its sales are in decline, and even Tiffany & Co.’s shine diminished since it initially flourished with its association with Audrey Hepburn’s famous movie, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Moats often enable companies to price their products robustly enough to result in significant profit margins and excellent returns on invested capital. For example, hidden inside our holding of Berkshire Hathaway is the insurance company GEICO. GEICO’s low-cost, consumer-direct model is the moat that has enabled it to take share from more expensive agent-led companies like Allstate and State Farm for years.

Today’s moats are constantly under attack

Software is an industry whose moats do not appear strong from a theoretical perspective. In fact, there are many cases of disruption, such as Adobe vs Corel or Salesforce vs Siebel, as companies must always be evolving and adapting. And, differentiation is only sustainable if a company continues to invest and stay ahead of the next guy. As Intel’s co-founder stated, “only the paranoid survive.”

In an industry as “simple” as writing code, and enabled by many existing software applications, open source, and now AI, developing a great program is not the highest hurdle to becoming a successful, multi-billion-dollar enterprise. There have been numerous cases where a dozen vendors provide essentially the same product, albeit “differentiated” by a slightly different user interface, slightly different use cases, slightly different go to market strategy, or slightly different customization, etc. While the goal is for IP and domain expertise to make it harder for others to replicate, we seldom find that to be the case.

From SaaS to PaaS and from front office to back office, we see multiple cloud providers and database solutions across all applications (digital marketing, ERP, payroll, collaboration, security, etc.). Even for highly successful companies like SNPS and Adobe, which are durable businesses and high-quality franchises, there is the constant ‘threat’ of alternatives. But the bigger players are usually in a scaled position of investing more, buying more, and are better equipped to survive, and have a broader product offering than the competition. Ultimately these companies succeed in building a brand and an offering that becomes a standard.

Unsurprisingly, Adobe is no stranger to attacks on its moat. It is differentiated by its ability to deliver mission-critical solutions that make creative professionals’ jobs easier and allow them to deliver high quality products to their customers. By bringing value to its users, Adobe has kept its moat sturdy enough to continue gaining users and staying relevant.

Adobe is experiencing the well familiar pressure with the exuberance over AI. As we expected, Adobe has already been investing in AI/ML, with the 2016 introduction of Sensei, its AI tool for digital marketing as a prime example. True to its strategy, Adobe’s priority on user experience is driving the discussion on the scale and speed of monetization for the additional AI features it is rolling out. Adobe’s current focus, which we think is the right strategy, is to increase the number of users and expand its ecosystem. Whether it is helping with idea generation or delivering more volume of content, AI is helping users become more productive and ultimately more reliant on Adobe solutions.

New companies can also enjoy well-established, traditional moats

Intuitive Surgical is another example of a “new moat” company. Intuitive develops, produces, and markets a robotic system for assisting in minimally invasive surgery. It also provides the instrumentation, disposable accessories, and warranty services for the system. The company has placed more than 8,000 da Vinci systems in hospitals worldwide.

Initially, Intuitive was primarily a monopoly with a unique product and, as a first mover, it had the opportunity to embed its surgical robots in hospitals and train surgeons on the use of its products. More recently, companies such as JNJ and Medtronic have attempted to create competitive products. But with its long history of working with surgeons in numerous hospitals, Intuitive has established two formidable moats:

1. Switching costs. Once physicians have become adept at using the Intuitive robot to perform numerous surgeries, it becomes a disincentive to leave this ecosystem. From the hospital’s perspective, there are workflow and supply chain benefits to standardizing a single robotic platform, and Intuitive continues to see rapid growth within its largest customers. The robots are expensive, and with the average system price around $1.5 million, this represents a large portion of a typical hospital’s annual capital expenditure budget such that customers would need a compelling technology or price difference to switch before their machines wear out naturally (the upgrade cycle is around five to eight years).

2. Scale. Intuitive’s growing clinical database on robotic surgeries performed globally gives it a huge body of data and experience – over 14 million procedures have been performed to date and over 76,000 surgeons have been trained on da Vinci systems. This enables Intuitive to not only improve its own products but to make the surgeon’s experience more user friendly and successful. For example, Intuitive is developing higher level services that help with training, planning, and conducting the surgery, and helping hospitals analyze their surgical practices. We believe that new competitors would face steep hurdles in trying to replicate a similar model. Meanwhile, Intuitive continues to raise the competitive bar with the development of its own next generation system.

In addition to Intuitive Surgical, our holdings Google and Mastercard enjoy network moats whereby their dominant platforms beget more and more users.

Conclusion

Far from castles and the countryside, moats are one of the first things we look for at Vontobel Quality Growth when considering a new investment. Moats can be wide or narrow and can change over time. We believe that many companies owned across our portfolios have significant moats. It is our goal to find companies with enduring competitive advantages in order to consistently provide our clients with strong, risk-adjusted portfolio returns over the long term.

Important Information: The views expressed in this material are the views of Vontobel through the period ended February 2024. Historical analysis and current forecasts do not guarantee future results. The information herein reflects our judgments, which are subject to change without notice, as of the date of this document. In preparing this document, we have relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources. Opinions and estimates involve assumptions that may not prove valid. There is no guarantee that any forecasts or opinions in this material will be realized. Charts are provided for illustrative purposes only. Discussion of the Vontobel strategy holding and other companies, if any, is for informational purposes only to elaborate on the subject matter under discussion. Investments referenced should not be considered as a reliable indicator of the performance or investment profile of any composite or client account. Further, the reader should not assume that any investments identified were or will be profitable or that any investment recommendations or decisions we make in the future will be profitable. No assumption should be made as to the profitability or performance of any company identified or security associated with them. Investments involve risks. The value of equities and equity-related investments may vary according to company profits and future prospects as well as more general market factors. In the event of a company default (e.g., insolvency), the owners of their equity rank last in terms of any financial payment from that company. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. The information provided does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security. It does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status or investment horizon. All information is from Vontobel unless otherwise noted and has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. There is no representation or warranty as to the current accuracy, reliability or completeness of, nor liability for, decisions based on such information, and it should not be relied on as such. © 2024 Vontobel.