Where are emerging markets going? Six questions answered

Quantitative Investments

Mid-May, China slashed its mortgage interest rate in a bid to prop up its economy as it clings to its zero-COVID strategy which has been hampering growth due to renewed lockdowns. This move has drawn attention to sluggish Chinese growth as one of the main factors, which next to rising US yields, an emboldened US dollar, and a prolonged Russia-Ukraine conflict, has been weighing on emerging markets (EM) this year. In this article, Gianluca Ungari and Sven Schubert will make sense of the swirl that has gripped the region to provide guidance for investors who are waiting for more clarity on the EM trajectory.

In EMs, much seems to have been priced in already which means we could already be past the trough with a silver lining emerging on the horizon for medium to long-term investors looking to make use of attractive entry points.

1. Where are EMs in the cycle now?

Sven Schubert: Currently, emerging markets are in the midst of an economic contraction as indicated by our big data-based business cycle model Wave . Economic activity started to slow down already in early 2021 triggering the beginning of underperformance of emerging market assets. By December 2021, emerging economies were sending clear contraction signals. While China was the main culprit for the slump in the region, aggressive policy tightening in major Eastern European and Latin American economies led to a cyclical slowdown in other regions as well. Chinese economic activity decelerated further once weak growth started to trigger defaults of leveraged real estate developers. Moreover, global supply side constraints worsened due to the Ukraine crisis, China imposed new COVID lockdowns in major cities and the surge in global yields has been undermining growth prospects in other EM regions, in particular in Eastern Europe.

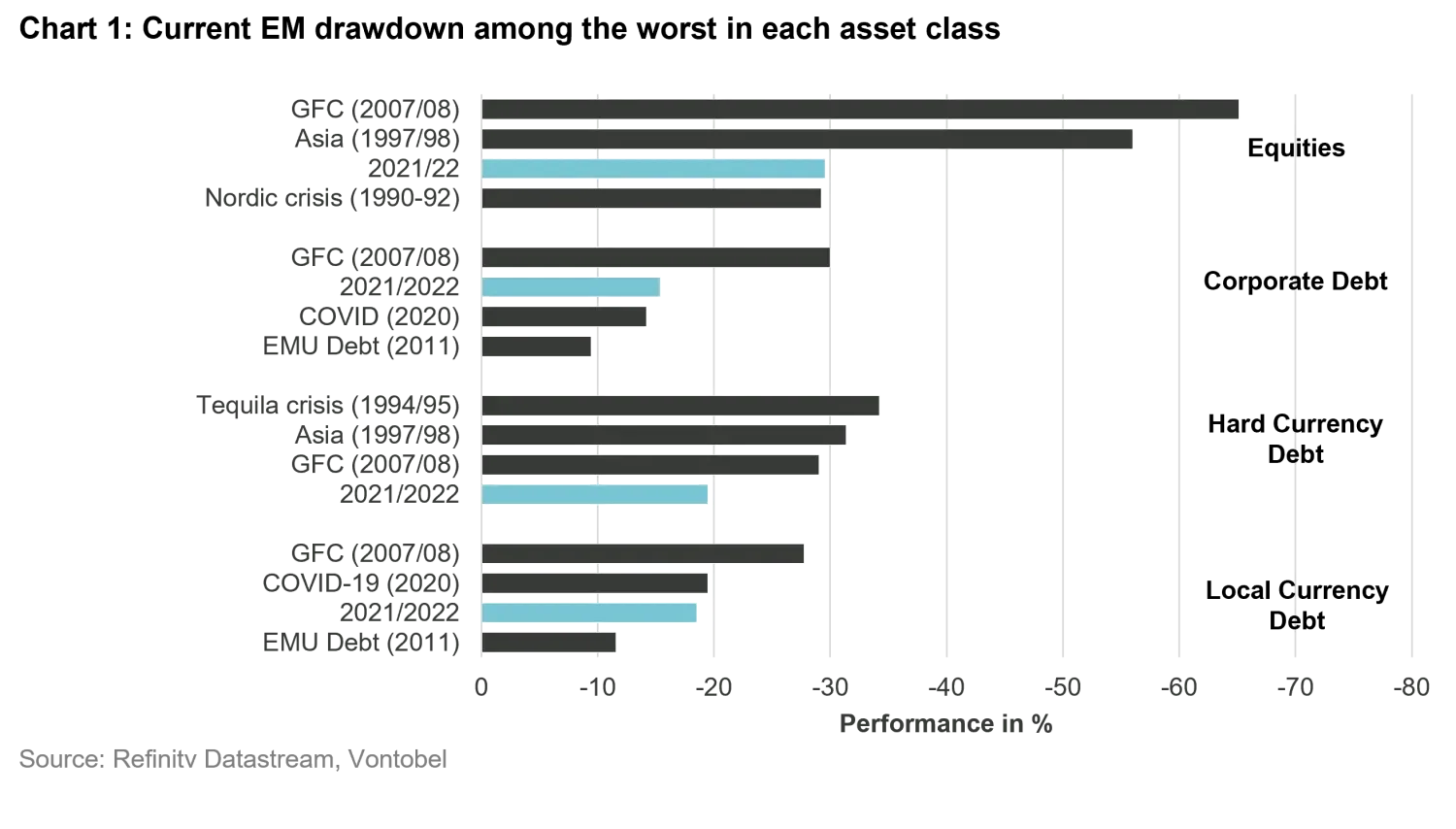

EM asset price depreciation already started in 2021 on the back of the Chinese slowdown in February first affecting mainly equities. By the fall the crisis had spread to EM debt markets due to surging US rate expectations. The Russian invasion in Ukraine earlier this year has aggravated this drawdown turning it into one of the deepest in each asset class over the last two decades (chart 1).

For now, EMs might still be sending mixed signals but a recovery signal could be in the offing soon. This is because, if history is any indication, we appear to be approaching the end of the contractionary phase – at least considering historical averages on a global level. Since the early 90s, contractions have on average lasted for seven and a half months and we are currently in month six. A word of caution: there are exceptions to this rule like the bursting of the dotcom bubble which triggered a contraction of 15 months. Longer contractions usually build on structural vulnerabilities in the economy such as many equity heavyweights being overvalued despite shallow earnings or real estate markets collapsing on the back of policy tightening against the background of high leverage in the banking sector. Often, contractions end with central bank policy shifts and loser financial conditions, like in December 2018, when an indication of a potential rate cut turned economic sentiment around. The Russia-Ukraine war could end up extending the current contractionary phase beyond the historical average, since a prolonged conflict would have nefarious effects on economic activity mainly due to elevated commodity prices.

2. Are Fed tightening cycles always bad news for EMs?

Gianluca Ungari: No. However, this is a myth which has proven particularly sticky with investors. An analysis of Fed tightening cycles since 1994 shows that despite rising US rates weighing heavily on EM equities, hard currency and local currency debt at the onset of hiking cycles, all asset classes tend to find a bottom already early in the tightening phase. The bottoming usually coincides with the peak in expectations on major central banks interest rates. In the current environment, we could be approaching this peak but for it to materialize, we would need to see inflation and inflation expectations decreasing as well as the US labor market cooling off over the coming months.

The link between rising US yields and EM asset prices is more complex. In case of sharply rising US yields, as seen lately on the back of surging inflation, EM assets tend to depreciate – a reaction which is often amplified if EM fundamentals are weak, like in 97/98 for example when current account deficits were high. This time, fundamentals have improved in several areas. Not only currency reserves increased over recent years, but also current account balances post a sizable surplus in many countries. In addition, EM carry is well above historical averages as several countries pre-emptively established a decent interest rate buffer in nominal and real terms already 15 months ago (chart 2). And, many countries are likely to tighten the screws even further.

3. Recently, EM currencies have lost significantly against the USD. Is this a sign of fundamental weakness of EMs?

Sven Schubert: Not this time round, no. In fact, considering how steep the current dollar appreciation has been, EM currencies have held up fairly well so far, also in comparison to previous US dollar rallies.

It would be misleading to expect EM assets to simply shrug off US dollar rallies of the current magnitude. But solid fundamentals can soften the sell-off, which is what happened this time. EMs pursued proactive monetary policies and started raising rates already one and a half years ago, in contrast to developed markets. This has put real rate spreads at levels last seen in 2007/08. At that time, that level of real rate buffer was sufficient to stabilize EM assets at the end of the GFC. The Brazilian Central Bank has been the most aggressive, raising the policy rate from 2% to 11.75% since February 2021. This interest rate cushion in combination with the commodity boom let to a strong rally of the Brazilian real - even against the US Dollar.

4. With the USD rising, will EMs be able to continue to service their external debt? Are we going to see more defaults?

Gianluca Ungari: Debt sustainability is unlikely to become an immediate risk for major EMs at this moment in time. The reason is that debt levels are also a significant issue to DMs which is why DM central banks should be keen on keeping real yields relatively low for some time to come. One way of achieving this goal is to allow for higher inflation, which is why the Fed adjusted their policy response function in 2020. In the new regime, the Fed is allowed to overshoot the inflation target to the same extent as it undershot the target over recent years. Even though the spike in inflation and tighter US monetary policy have pushed US real yields back into positive territory, we are still far away from this decade's average of 2%. Moreover, recent US polls suggest that the Republicans may win back the Senate and Congress in the mid-term elections, which would be a headwind for US fiscal spending which could further increase real yields.

Outside the US, more prudent fiscal policy is necessary to keep the longer-term sustainability risks in check. In particular, China should tread with caution as the country carries a debt burden of 360% of GDP (excluding financial institutions).

5. Will Chinas economic slump continue to be a drag for EMs?

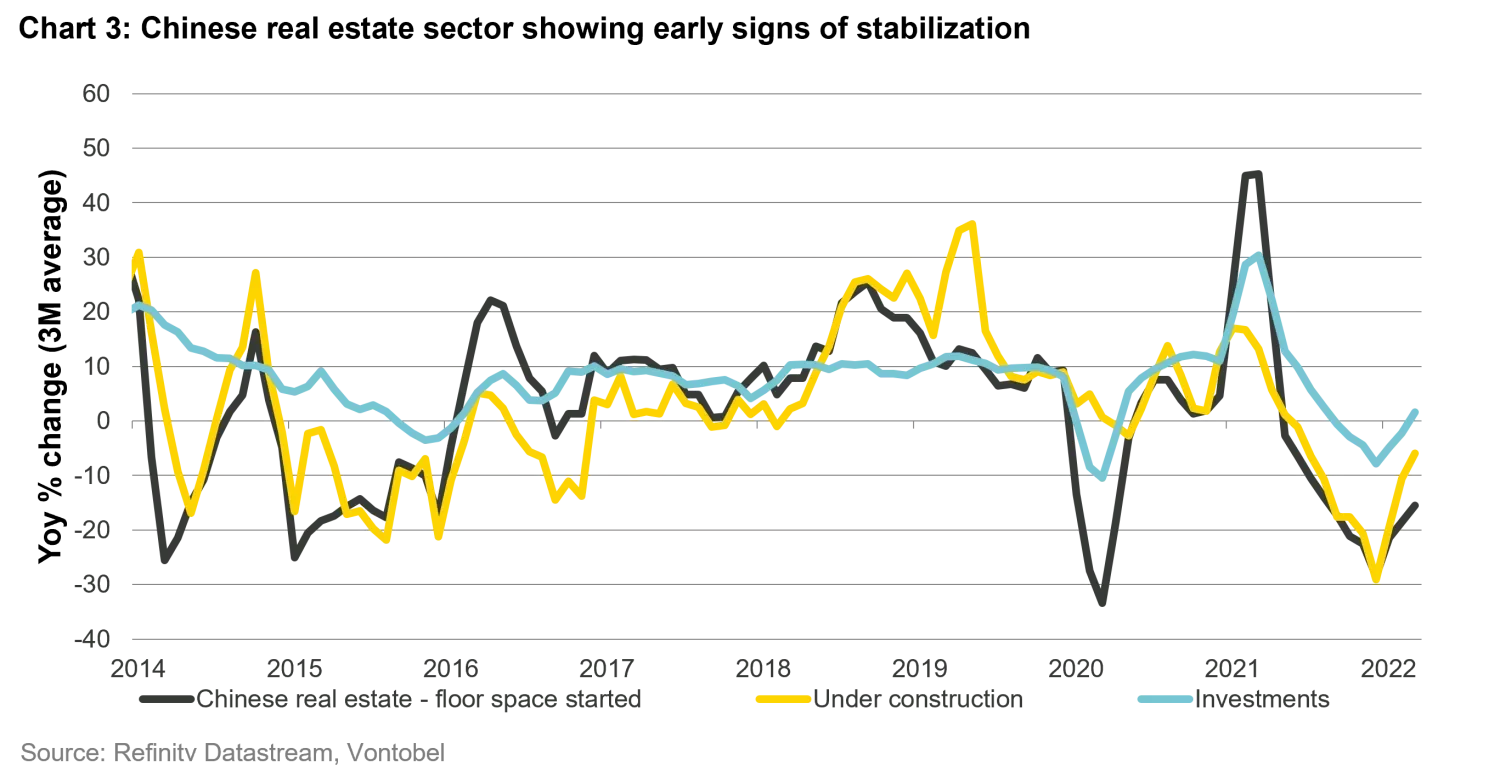

Sven Schubert: This depends on how successful China will be in balancing its unrelenting zero-COVID strategy and economic growth. In Q1, the country seemed to be approaching the bottom of economic activity as financial conditions eased and credit impulse turned positive. However, this picture has been blurred as new COVID lockdowns were imposed in spring leading to a collapse in Chinese activity data with retail sales contracting by 11% year-on-year, for example. Growth stabilization has certainly risen on the priority list of the Chinese government and the recent cut in mortgage interest rate is a testimony to that. In addition, the government is likely to adopt a more cautious approach to regulating its real estate sector which has been responsible for much of the country’s slowdown over the past year. This means, on the one hand, making sure that the majority of sound developers is well supplied with refinancing sources and, on the other hand, supporting the signs of recovery that the sector has started to show as of late. For example, investment in real estate has started to pick up, although it still remains at depressed levels. Moreover, the construction activity of residential and office buildings as well as buildings for commercial business seem to have passed their troughs (chart 3).

Even if the recovery of Chinese real estate is still in its early stages, the government remains focused on increasing the “quality” of growth by reducing leverage rather than pushing up the “quantity” of growth. As a consequence, the Chinese government is unlikely to delay its clean-up of banks' property loan books which could prove another headwind, albeit not a stumbling block, for the Chinese growth recovery. Stress tests point to a rise of non-performing loans from 0.9% to 2.2% of banks' total loans. This is still shy of critical levels (~5%) but high enough to affect banks' risk appetite. The focus on high-quality growth also means that any economic stimulus will only be temporary until a recovery sets in and not the start of a longer stimulus cycle, even if the self-imposed growth target of 5.5% for 2022 will almost with certainty turn out to be unattainable. In any case, stimulus measures will only be effective if lockdowns are lifted and economic activity can resume in major cities.

6. Will the Russia/Ukraine conflict hamper an EM recovery?

Gianluca Ungari: The risk of this happening is certainly there. Our analysis shows that the main channel of contagion of the war is via higher commodity prices and possible shortages in Russian energy supply with diverging effects on EMs. While Latin America is benefiting due to their commodity-heavy export structure, some are facing negative effects due to their dependencies on Russian and Ukrainian commodity exports (Europe) or higher global energy prices (CEE, Turkey, India and China). The biggest risk is that Russia will start using Europe’s dependency on Russian energy supply rather sooner than later in the negotiation process, before Europe can effectively reduce its need for Russian energy. Supply cuts to countries such as Poland have been taken place already. Higher agricultural prices remain an issue as well for consumers in EMs, but the effect is likely to be more relevant for frontier markets due to the higher weight of grain in their consumer basket. However, energy price effects are unlikely to derail the Chinese growth acceleration over the next few quarters as Russia is unlikely to leave China high and dry.

Conclusion

As geopolitical risk remains difficult to quantify and wobbly Chinese real estate markets remain a risk, it might be a little too early to dip your toe into EMs already now. But while China steps up stimulus and loosens monetary policy, growth momentum in developed markets is weakening and monetary conditions become tighter. As diverging policy paths between EMs and DMs tend to coincide with a relative outperformance of EM assets, investors should start looking out for opportunities to re-enter the market.