Investors should remember – Powell is not a bond manager

TwentyFour

It feels like we are currently spending at least 40% of our time talking about inflation, or more accurately, why the US Federal Reserve seems to have a different view of inflation to almost everybody else.

For bond managers, the anxiety around inflation is understandable; it typically means losses in US Treasuries, which in turn can impart losses on credit products where the spread is too slim to absorb the rates move. The endless headlines this topic seems to generate may prompt some eye-rolling, but we think it is a debate well worth having. In my opinion, if there is one call investors need to get right in the remainder of 2021, it is this one. And if there is one thing for bond managers everywhere to remember, it is this – Jerome Powell is not one of you.

For months, Federal Reserve chair Powell and other Fed officials have served market participants an increasingly familiar diet of reassurance and a continuing commitment to support the post-pandemic recovery for as long as necessary.

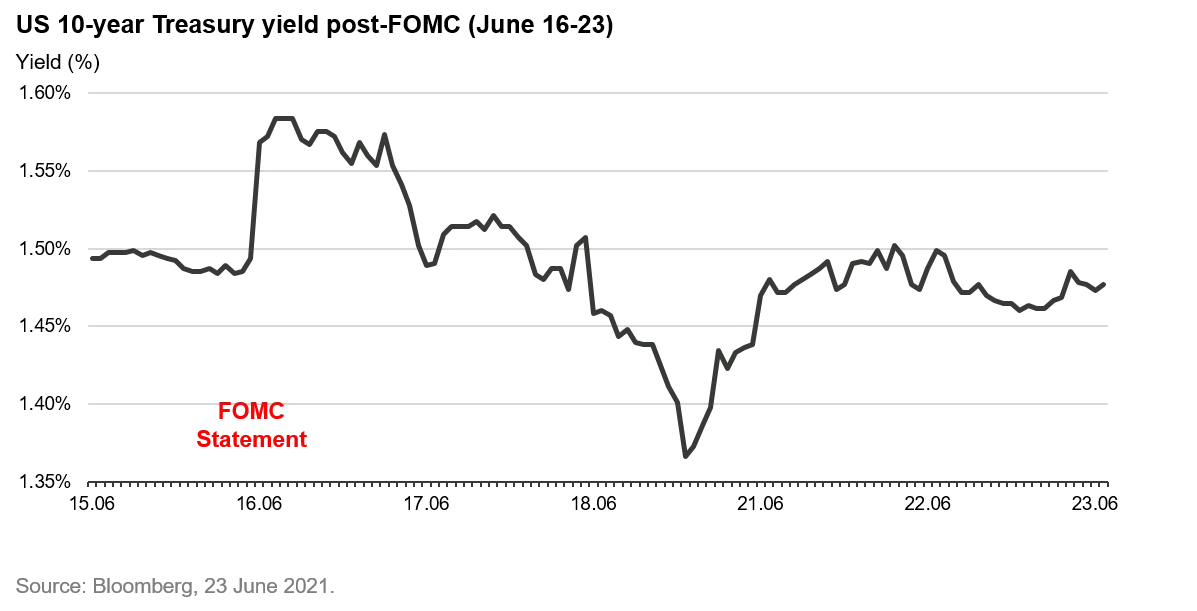

That was until the latest Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on June 15-16, when the updated ‘dot plots’ showed individual Fed members becoming more hawkish (the median dot plot now predicts two rate rises in 2023). Likewise, the Fed also sharply raised its own inflation expectations for 2021 from 2% to 3%.

Despite what was regarded by many as a ‘hawkish turn’, Powell again stressed that the pace of the Fed’s asset purchases would continue until “substantial further progress” was made on employment and inflation, and he also downplayed the significance of the dot plots. In the face of apparently conflicting signals, US Treasury yields reacted accordingly, initially jumping to 1.58% before settling at their pre-meeting level of 1.48%.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will not be actively managed.

At the core of Powell’s messaging is the Fed’s continued assertion that any evidence of price inflation during the present phase of the recovery will prove transitory and ultimately dwindle in the face of prevailing disinflationary secular trends of globalisation, de-unionisation, low population growth rates and automation.

However, recent data points taken in isolation could lead an investor to regard the Fed’s repetitions as ringing hollow. For example, in April, the US Consumer Price Index reflected annual price rises of 4.2% against expectations of 3.6%. An acceleration of 5% followed in May against survey estimates of 4.7%. Is all of this uptick actually going to be transitory?

What is going on here – is the Fed behind the curve?

We cannot discount the meaningful influence base effects had upon the recent inflation prints. The significant year-on-year jumps partly reflect the depressed price levels during the period when COVID-19 restrictions were most severe. Accordingly, base effects were most evident in those sectors severely affected by COVID-19, which may point to transitory inflation that could normalise as reopening pains ameliorate.

And yet, from our perspective, the potential risk of more durable inflationary pressures is not entirely absent from the horizon. To be clear, we are not predicting a new regime change here – the disinflationary pressures that characterised the global economy pre-pandemic remain largely intact, but there are a number of reasons why we think we will see higher inflation than the Fed currently seems to be expecting.

First, it seems naive not to expect some loss of economic efficiency after closing the world down for a year and reopening rapidly, and the US labour market is already showing signs of these frictional costs developing. According to a paper released by Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta in June, wages for new hires in relatively low wage jobs surged 7.7% higher than expected during the first quarter, with many commentators conveying that the rapid reopening and generous unemployment benefits were conspiring to force companies to raise wages. Supply shortages in key inputs such as semiconductors and surging commodity prices also point to the difficulty of restarting global supply chains when economies aren’t all restarting at the same rate. Combine this with a global banking system that, unlike in the period post-financial crisis, looks to be well capitalised and inclined to provide credit, and we believe there are enough reasons to anticipate inflation being more persistent than the Fed’s stance would indicate.

Should we as bond managers be worried that our view on inflation appears at odds with that of the Fed? Well, not necessarily.

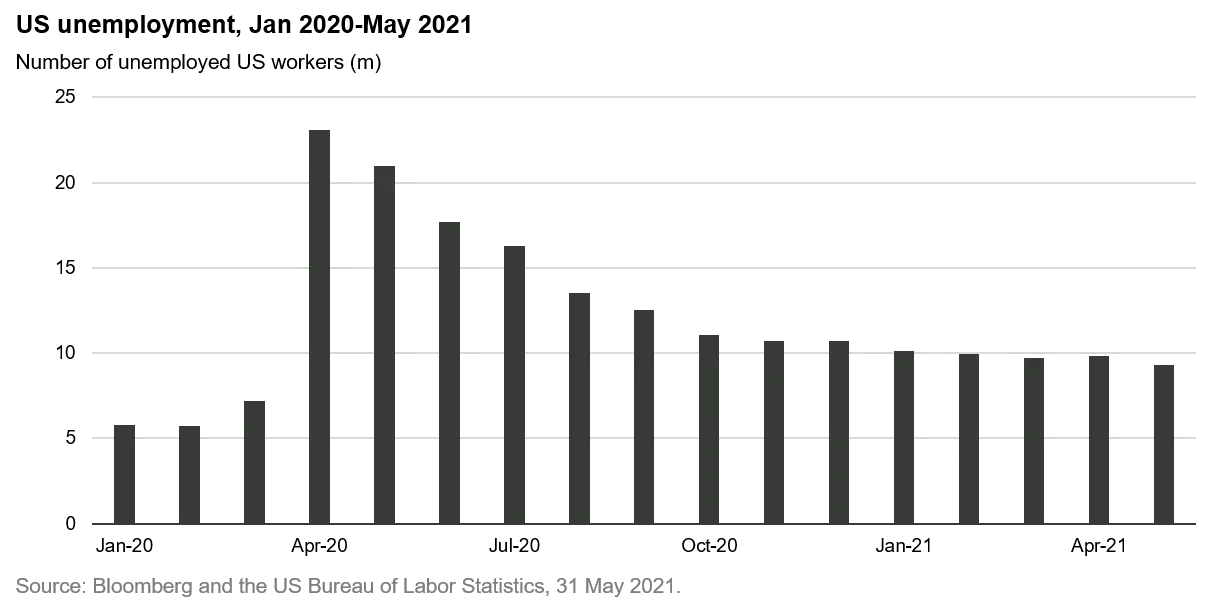

Put simply, Jerome Powell is not a bond manager. While signs of elevated inflation preoccupy bond investors globally, the Fed’s dual mandate means the pressing issue for Powell is full employment and ensuring the recovery happens evenly across the US population. Therefore, it appears understandable that Powell and the Fed may consider a period of above-target inflation a price well worth paying for getting eight million unemployed US workers back into jobs.

So perhaps the Fed is behind the curve, but in my view, it is happy to be. The Fed’s job right now is to foster the recovery and avoid making comments that would make the market question that commitment. As bond managers, our job is to get a decent return on our assets. In my view, the key to doing so during the remainder of 2021 will be managing the risk of another rates sell-off while making sure we remain exposed to what appears to be a rampant economic recovery and rapidly improving credit fundamentals.

From our vantage point, the most pertinent consideration is managing exposure to what history indicates are the most duration sensitive sectors because we expect the Fed to be much more inflation tolerant than we as bond managers can afford to be. Therefore, considering trimming exposure to even high-rated, duration sensitive sectors seems to us to be a prudent move. Likewise, pragmatism dictates a slight reduction in overall risk in case we experience some volatility while the Fed toys with its messaging and the uncertainty that might create. Therefore running portfolios with a marginal increase in liquidity to target attractive valuation opportunities should they present themselves makes sense to us.

However, we are not advocating a wholesale rotation from risk assets; we still believe credit sectors will continue to perform positively and tighter spreads are ahead of us in this cycle, particularly where the credit component of the security is the dominant price driver, not the rates connection.

Overall, our message is: In the face of an uncertain inflation trajectory and labour market outlook, retaining a little more cash to target potential dips while reducing exposure to duration sensitive sectors may prove an effective strategy in the second half of 2021.