Outlook 2023: Proceed with caution

Quantitative Investments

As financial markets digest the harsh reality of an inflation-induced rate hiking cycle this year, 2023 is likely to be a period of adjustment to new conditions requiring fresh approaches to asset allocation and portfolio construction. In this outlook, we outline the essentials that investors should know to reap the potential of profoundly altered markets.

Macroeconomics: despite retreat, inflation likely to stay elevated

Yes, inflation is most likely already past its peak in the US and possibly in Europe but may stay at elevated levels for a prolonged period next year and beyond.

Here is why.

Due to easing base effects mainly driven by decreasing commodity prices, we are likely to see falling year-on-year inflation numbers in 2023. However, central bank policy is likely to remain tight until the second half of 2023 as policy makers will want to see sizeable decreases in inflation before they let up. Actual rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed), however, are unlikely before the end of 2023 or even the beginning of 2024 depending on the trajectory inflation is going to take.

While decreasing inflation numbers is of course welcome news, markets might be in for a surprise when inflation gets sticky well above major central banks targets next year. Large deflationary trends, such as digitalization and technology, are still under way, but in the medium term they could be outweighed by inflationary drivers. This is because the risk of further supply-side commodity price shocks has not yet entirely subsided which will make it difficult for prices of manufactured goods and other commodities to come down from elevated levels. That is, unless there is a broad-based reduction in demand. In addition, wages have started to rise in many countries, gradually increasing their share of national income due to the pandemic-related overstimulation of many economies. Moreover, cost-intensive nearshoring has risen in popularity as persistent geopolitical risks and crises have increased awareness that far-away trade dependencies may disrupt longwinded supply chains, severely affecting business results. This has been driving the momentum of bringing production facilities closer to home, which has companies shifting away from lowest-price producers for the sake of supply chain and production stability. Finally, above-target inflation may even be a welcome remedy to ballooning government debt as the real value of outstanding government debt falls when inflation is on the rise.

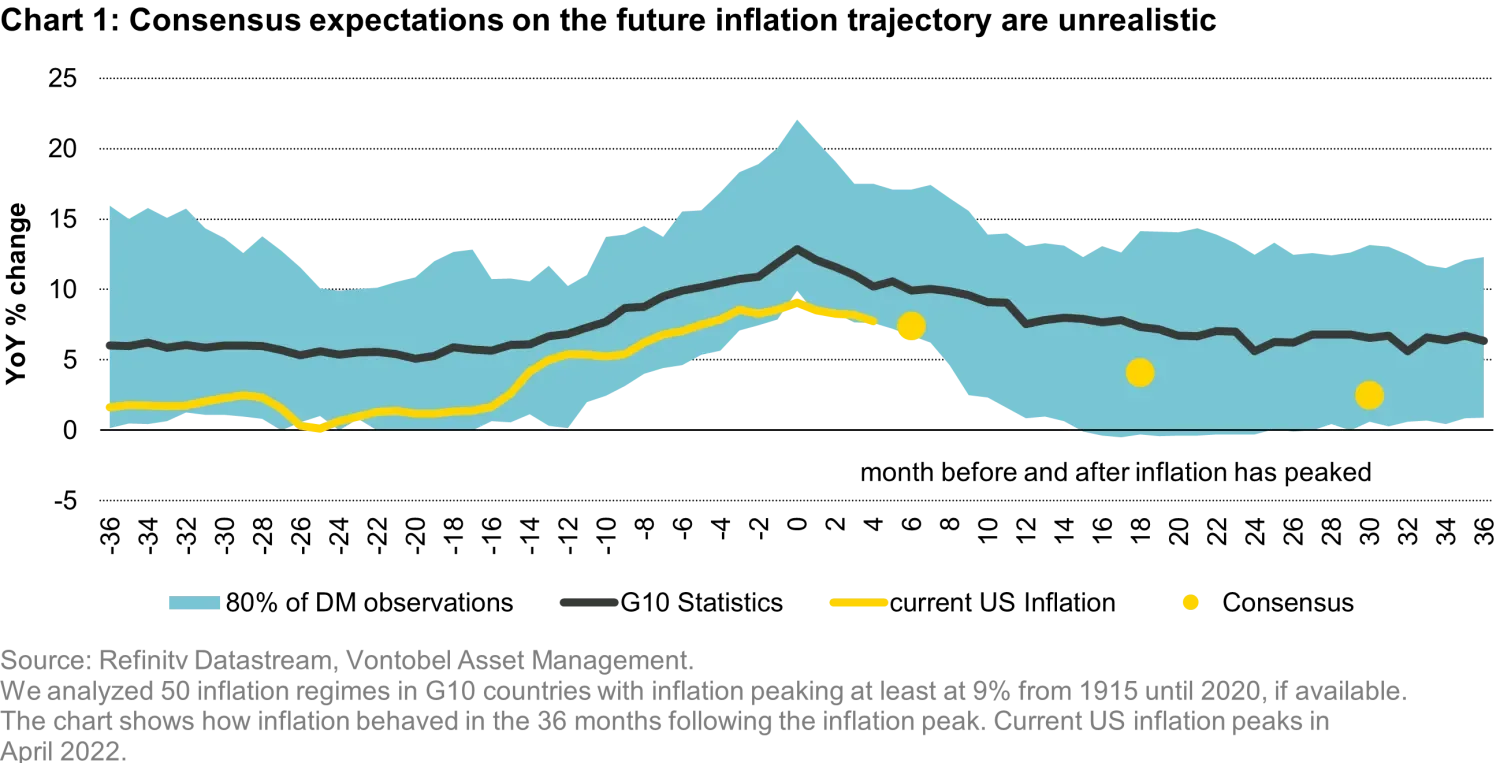

Considering these inflationary trends, expectations that inflation will return to central bank targets in 2023/24 without a recession seem unrealistic. An analysis of high-inflation regimes in developed markets (G10) since 1915 shows that bringing inflation back down to target levels is a difficult and lengthy endeavor. Chart 1 illustrates that on average inflation only halves from its peak within 24 months, whereas current consensus is expecting a much faster pace. High expectations give ample room for potential disappointments, especially since inflation rarely takes a linear path. Therefore, volatility will be part of the picture as markets oscillate between euphoria and despair while central banks arm-wrestle with inflation.

Expected GDP output loss of about 2% next year

In a frantic search for indicative central bank support, markets are celebrating every miniscule retreat by inflation. Meanwhile, the global economic engine has started to stutter as the effects of the current central bank hiking cycle are making themselves felt. In fact, a recession in Europe and the US in 2023 might very well have to be taken as a given. Despite first signs of easing, the continued strength of the global labor market does not allow the Fed to end its policy tightening cycle in the next few months. Two IMF economists conclude that the Fed's forecast can only be reached under optimistic assumptions and the condition that the unemployment rate may need to rise to 7.5% to bring inflation back to target1 - even though the housing sector and consumers have started to feel the pain of tightening already and margins are shrinking. As a result, major developed market economies are currently in contraction with only slim chances at a recovery according to our global business cycle model Wave 2 (see chart 2). Europe could even be the first one to enter into a recession as the continent has to grapple with the current war in Ukraine, an energy crisis and increased risk of political fragmentation which complicates the task of the European Central Bank to normalize its policy.

In response to the most pressing question of “how bad will it get”, we ran an analysis on 10 developed countries tightening cycles since the first half of the 20th century to find out what level of GDP output loss we are likely to face. Despite the relatively high variation of the results, the analysis has shown that policy tightening of around 5%, which is likely to be the terminal Fed rate, can be expected to cause an output loss of up to 2%. While DM economies should be able to stomach an economic slowdown of this magnitude, there are some downside risks to that scenario as the current hiking cycle is one of extraordinary speed after a long period of ultra-loose monetary policy which puts high strains on markets and the economy alike. Therefore, a GDP output loss exceeding 2% cannot be excluded.

Moreover, our analyses of economic recoveries show, that the conditions for a sustainable recovery are not yet given. In most cases of G10 countries, easier monetary policy in form of rate cuts, bond yields, easier financial conditions and fiscal policy are a precondition for a sustainable recovery. While it is true that financial conditions and bond yields have been falling since October, the policy tightening cycle has not yet ended, and the pace of the Fed balance sheet reduction is accelerating. Fiscal policy has yet to become supportive too. Therefore, the risks of a recession have rather increased over recent months, despite easing financial conditions.

Emerging markets will have to prove their worth again next year

As opposed to developed economies, the bloc of emerging markets has been oscillating between recovery and contraction lately, mainly due to China and Latin America. While Latin America is being carried by the tailwind of higher commodity prices, China remains a bit of a wild card as its economy is trying to stabilize after having reached its bottom in Q2 2022. On the one hand, renewed COVID-19 infection waves and significant lockdowns pulled China and, therefore Emerging Markets as a whole, back into contraction. On the other hand, China is laying the groundwork behind the scenes for relaxing its unrelenting zero-COVID policy. Supporting measures to the country’s housing sector have been ramped up as well over recent weeks, which should get housing back on to a more stable footing. Inflation is unlikely to become a headwind for Chinese authorities as consumer prices are more closely linked to regional price mechanisms and country-specific deflationary elements, such as housing. As a result, Chinese monetary and fiscal policy can be expected to remain supportive in the first half of 2023 and gradually trickle through to accelerating economic momentum.

Despite these positive factors, China is likely to fail its growth target of 4.5% this year and possibly next year too, which is needed on average over the upcoming 10+ years to achieve its strategic objective of doubling the country’s GDP per capita by 2035 compared to 2020 levels. In addition, political risks such as increased regulatory scrutiny, China's more assertive foreign policy and Latin America’s political shift to the left have increased significantly over the past years questioning EMs as a core component of strategic asset allocations. EM equities are currently still trading at distressed levels harboring value potential for investors, but the long-term outlook for China has become an enigma due to unpredictable politics and doubtful growth perspectives.

Asset allocation needs fresh approaches due to higher correlations

Asset allocation is likely to require fresh approaches as of next year since correlations across asset classes have risen reducing diversification potential in the market. This is because surges in inflation often go hand in hand with rapid increases in expected short-term rates, which have negative effects on equities and bonds alike, prompting them to move increasingly in tandem. This causes higher correlations, not only between these two asset classes but also within them, across regions as well as sectors.

Equities: Active diversification will be key

The trajectory of equities will be a volatile one next year as they are closely tied to the inflation vs growth dynamic that is playing out in markets. Often, equity markets only find a bottom just before a recession, which we expect in Q2 2023 for the US. This means that simply riding the wave of market beta won’t yield attractive investment outcomes anymore. Instead, investors should look to actively manage their positions across regions and countries, while diversifying across factors as well as strategies to uncover equity alpha going forward.

As long as uncertainty over the severity of the recession and crucial exogenous factors remains high, flexibility with regards to relative allocations between the US, Europe and emerging markets will be of the essence. Currently, US equities benefit on a relative basis from the advanced stages of the Fed's monetary policy, yet higher valuation levels carry further downside risks especially in a deep recession scenario. While European equities are currently trading at attractive levels, their future path will be decided by the war in Ukraine as well as the energy crisis. The same applies to emerging market equities, that are weighed down by China's unrelenting zero-COVID policy and ongoing real estate crisis. China, which dominates the bloc's performance, has become difficult to decipher due to unpredictable politics and doubtful growth perspectives. Nevertheless, as a tactical play, both EMs and Europe can be interesting alpha sources within a well-diversified equity position until the fog has lifted over the recession next year as well as China's long-term development.

In terms of factors, quality and growth are most hit during a recession whereas value can offer some stability. Growth stocks derive their value from cash flows projected far into the future, so a deteriorating growth outlook coupled with rising interest rates has a strongly diminishing effect on their present value. While quality stocks are, as the name implies, high-quality, they tend to have a high price tag exposing them to strong volatility and downside risks when uncertainty increases in the market. Value with a defensive tilt can make up for lost income on the fixed income side by virtue of a stable dividend yield, in particular, if the economic outlook worsens.

In addition, trend-following strategies can prove useful next year as equity volatility requires highly reactive strategies that are able to convert volatile market movements into portfolio returns at a fast pace. By riding the wave of the trend, these strategies have the potential to capture big price moves in the market and avoid major losses, improving risk-adjusted returns.

Bonds: playing the front end of the yield curve

At least in the short to mid-term, bonds have lost their position as a structural diversifier in investor portfolios due to their rising correlation to equities. Moreover, inflation and rising rates paint a bleak picture for bond prices. However, yields have risen in tandem with interest rates and have reached attractive levels again offering interesting entry points for investors waiting on the sidelines for renewed opportunities.

Based on the calculation that much of central bank hawkishness has already been priced in as things stand today, the front end of the government bond curve is the most promising place to be for investors next year. This is because they are the most effective way to play the Fed pivot while also offering some shelter against future volatility considering they have already largely absorbed expected rate hikes. Once rate cuts resume, yields on the front end will fall the most, driving attractive portfolio gains. As long as economies are still in limbo over how deep their recessions will be and inflation is still way above targets, long-duration bonds are to be treated with caution due to their high interest rate sensitivity and higher correlation with the equity market.

Alternatives: rise and shine

Currencies have risen to new prominence as alpha sources and diversifiers lately and will take a more significant role in investor portfolio next year. On the one hand, currency pair trading harbors increased return potential as central banks pursue different interest rate paths in different regions and countries. On the other hand, currencies will embark on divergent trajectories as economies contract to differing degrees next year. The US dollar is a case in point. First, it was buoyed by the Fed initiating policy normalization ahead of all the other central banks. As a result, most currencies have devalued against the greenback. Now, the US dollar stands to benefit once recession fears take hold and drive investors into safe havens. Thanks to this behavior, the USD has become a strong decorrelator from other major risky asset classes that have mostly been on downward trends this year. Therefore, holding a position in the USD also next year, could have beneficial portfolio effects.

Within commodities, gold could finally take on its traditional role of a portfolio stabilizer real rates achieve a more stable footing next year. While a more diversified basket of commodities will be exposed to the waves of the economic cycle, it can serve as a tactical position to participate in larger structural trends fed by supply/demand imbalances and the transition towards greener economies.

1. See Ball et al. (2022) “Understanding US Inflastion in the COVID area”, NBER WP 30613.

2. See “

The Vescore Wave – a superior business-cycle model

”